This site was funded by

Incidence:

Trigger warning: there will be a discussion of suicide rates amongst students in this section.

Universities UK in their publication ‘Student mental wellbeing in higher education Good practice guide’ provide the following definitions:

“Mental health difficulties - often following major life events such as the end of a relationship, close bereavement or leaving home, can impact significantly on how students feel about themselves and how they engage with the transitions of student life. Symptoms may beset anyone at any time, giving rise to ongoing conditions that could interfere with the student’s university experience and have implications for academic study.”

“Mental illness - arising from organic, genetic, psychological or behavioural factors (or combinations of these) that occur in an individual and are not understood or expected as part of normal development or culture – can be acute or chronic, and may fall within the definition of a ‘disability’ contained in the Equality Act 2010.”

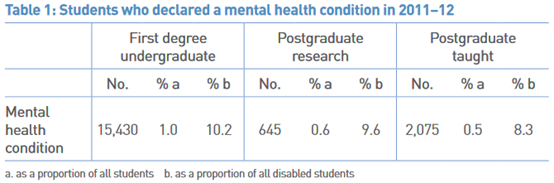

According to Thorley (2017)[1] rates of mental illness and distress in students have been increasing over time. The proportion of UK domiciled undergraduate entrants to university who declared a mental health condition rose from 0.4% in 2006/7 to 2% in 2015/16. Over the same period mental health conditions have made up an increasing proportion of the total disabilities disclosed. Mental health conditions represented 5% of disability disclosures in 2006/7 rising to 17% in 2015/16 with female and undergraduate students more likely to disclose. It is estimated that almost half of students with a mental health condition choose not to disclose it to their University. HESA data from 2006/7 showed that mental health conditions the second most prevalent disability within the student body after specific learning difficulties.

Bewick et al. (2008) found, in a sample of 1,129 students spread across four universities, that one third of students reported ‘heightened levels of psychological distress’, with 8% of the sample reporting that they experienced moderate to high levels of distress. In contrast to most other studies they found anxiety was more prevalent than depression within their sample.

Thorley (2017) also states that three quarters of individuals with mental health conditions will experience the first symptoms before the age of 25 and that students experience lower levels of well-being than equivalent non-students. Dahlin, Joneborg and Runeson (2005) in a study of 309 medical students in Sweden found a much higher prevalence of depression than is found in the general population, with higher rates of depression amongst female students.

There are a number of studies that show that various types of mental health conditions are more prevalent amongst individuals otherwise disabled. For example Carroll and Iles (2006) showed that students with dyslexia demonstrated high levels of both academic and social anxiety, albeit from a small sample.

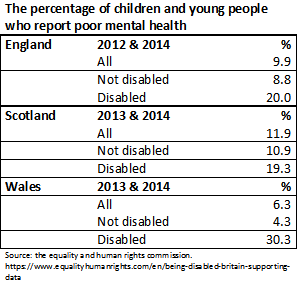

The Equality and Human Rights Commission provide data drawn from health surveys carried out in England, Scotland and Wales. Each of these surveys shows significant differences (at 1%) between the reported rates of poor mental health amongst children and young people who are disabled and those who are not.[2]

Characteristics:

Mental health conditions encompass a variety of illnesses, including conditions such as anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and psychosis, for example. It is difficult to generalise about the characteristics of such disparate conditions and individuals can be affected differently by the same disorder.

A good summary of the main features of several mental health conditions can be found here on the Rethink Mental Illness charity’s website.

Moving from home and school to university as a significant transition point in a student’s life. There are a number of changes in this process that could potentially trigger mental health difficulties or aggravate an existing mental illness. These changes include moving to a new region or country, making new friends, encountering new methods of teaching and assessment and establishing new relationships with new support services and local health provision (Universities UK 2015)[3].

Source: (Universities UK 2015) based on Equality Challenge Unit data.

Impact on teaching learning and assessment:

Thorley (2017) states that the consequences of ‘poor mental health and wellbeing’ among students include academic failure, repeating years, dropping out, reduced employability and suicide. In 2014/15 1,180 students who had disclosed mental health problems dropped out of university. Office for National statistics data published in 2018 shows that between the beginning of the academic year 2016 and the end of the academic year 2017 a total of 1,329 students attending higher education institutes in the UK committed suicide.[4] This gives an average of approximately 83 suicides each year with the highest number taking place in January (12.26%).[5]

Thorley (2017) also details a number of case studies showing good practice in a variety of UK HE institutions. In almost all of these cases actions are taken at the University level to change procedures, training and/or the ethos of the institution. Within these case studies the value of lecture capture to students who find attending classes difficult is highlighted as important as are robust mitigation procedures.

The University provides a number of guidance documents for staff.

General advice for staff: Wellbeing Services

The Welbing advice: Helping Distressed Students

References

[1] https://www.ippr.org/files/2017-09/1504645674_not-by-degrees-170905.pdf

[2] These surveys are not directly comparable as they measure poor mental health differently, are carried out in different years and are based upon dissimilar samples.

[3] https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2015/student-mental-wellbeing-in-he.pdf

[4] This data was published in response to a request for the number of HE student suicides by month. Whether months was not known data was excluded and so this is likely to be an underestimate of the true number of suicides. It also excludes cases where the coroner's verdict had not been finalised.

[5] https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/adhocs/008834numberofsuicidesinhighereducationstudentsbymonthofoccurrencedeathsregisteredinenglandandwalesfinancialyearending2001tofinancialyearending2017combined.

Summary of the most common impairments

An introduction to the characteristics of the most common disabilities