It is thirty years to the day since the broaching of the Berlin Wall. Ulrike Zitzlsperger, Associate Professor of German in the department of Modern Languages, reflects on her first-hand experience of the events and her teaching and research in this area in the years since 1989.

*****

On 9 November 2019 Berlin is once more the central location for celebrations commemorating the fall of the Wall, the physical divide between East and West Germany and unique symbol of the Cold War. In 2019 the Wall will have been gone for more years than it actually stood.

Developed from August 1961 to stem the growing exodus of a skilled work-force, the Wall allowed the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to become the success story of the Warsaw Pact. However, time and again people risked everything to escape to the West. Even if they were successful they left their former lives behind and knew that any remaining family would be punished by the state: costing them, for example, that much longed-for place to study at University or a trip abroad. There were more sinister options too. In Berlin, so-called frontier-city of the Cold War, the Wall encircled the Western part of the city, measuring between 3.4 and 4.2 metres in height. There is a memorable scene in Steven Spielberg’s film Bridge of Spies (2015), when one of the protagonists watches lone figures from the inner-city railway desperately climbing the Wall. The scene is fiction – just like the scene in the Alfred Hitchcock film Torn Curtain (1966) that makes us believe that GDR citizens hijacked buses with passengers on board to escape. The Wall never needed this kind of embellishment: it was sufficiently surreal, monstrous and overwhelming as it was, including the death-strip in between both Walls – one facing West, one East.

The build-up to the actual fall of the Berlin Wall had been steady: months of reports about people from East Germany leaving everything behind to move to the West while on ‘holiday’ in Hungary, occupied embassies, and thousands joining demonstrations in Leipzig and other cities. In the West and in particular in West Berlin we were glued to our television screens. Nonetheless, when the news broke that the border opened that night a sense of disbelief dominated. After all, we had grown up with the divide between East and West and learned about it in our history books at school. To us the Wall seemed permanent. In the event, happy speechlessness found a fitting expression: ‘Wahnsinn’, translating as ‘unbelievable, sheer madness’, though of course this sensation was utterly positive. It became the word of the year 1989.

Even more exciting than claiming pieces from the Wall that night was venturing through one of the newly opened crossing points towards Alexanderplatz in the East – against the tide of East Berliners coming to West Berlin. More than breaking pieces out of the Wall, this tentative, equally nervous and excited walk down a deserted road in ‘the other’ Germany provided us with a sense that no matter what we were experiencing history in the making.

In the months to come therafter, life in Berlin was sensationally exciting: we explored the East, the East explored the West (to a degree), while the city itself transformed before our eyes.

When I first taught the history of Berlin at Exeter people remembered the events of 1989 first hand. Some had heard pilots making announcements during a flight, others saw events unfold on television, and some had paid a fortune to come to Berlin. Among the first seminar group I taught was even a mature student who had been a pilot during the Berlin Airlift of 1948-49. The events of 1989 took centre-stage – as did the measures taken to determine how the divided city would be reunified: again, history in the making, right in front of our eyes.

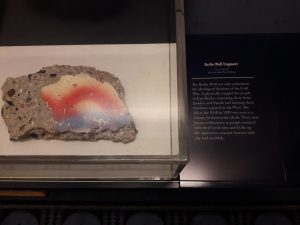

As time went by though, more and more of what had seemed all-important detail turned into footnotes: the story of the fall of the Berlin Wall became shorter and more concise, in teaching as much as in research. At one point, participants in a Berlin seminar had been born in 1989. And while it was a straightforward matter to explain why the Berlin Wall had been built, it became increasingly challenging to explain what it really looked like and why it was so hard to overcome it. Over time interests shifted: for a few years memory studies boomed. What was most interesting were the ‘competing memories’: whose story was it? The East’s, the West’s, or was a more international perspective possibly best? Is the Wall best remembered where it had stood – or in one of those places where the consequences could be felt: such as former prisons or transition camps for emigrants and refugees? Today Berlin is dotted with Wall remnants, even though many pieces were gifted to other states, sold or destroyed.

Berlin has turned into a number one tourist destination: history, and in particular history with a happy ending, sells. The numerous souvenirs are proof of that – few deal with the ‘real’ Wall, many focus on the Wall’s fall. Some look like the result of a 30 seconds brainstorming exercise. Examples include fridge magnets that show the East German car, the Trabi, breaking through the Wall (never!) and the graffiti that was only to be found on the West-facing Wall from the 1980s onwards (but not the collection of buzz words shown here). The recipe is simple: the Wall as a symbol, the Trabi as a nod towards daily life in the East, and graffiti to mark ‘cool’ Berlin, now proudly branded as ‘city of freedom’.

The current anniversary stands out for two reasons: the symbolism of the Berlin Wall at a time when new walls and borders are developed is more important than ever before. And quite possibly this is the last time witnesses are coming to the fore with the German and the international media showing such a keen interest: witnesses in the shape of those who lived with the Wall, those who saw its demise and then all those who were born since and who have heard about the Wall second hand. The actual Wall has moved to heritage sites and into museums – its original pieces serve as case studies in exhibitions: for example in Canberra in December 2018 in a display about democracy.

From here on the Wall is material for the history books again: a few facts and maps to be learnt by heart, the odd future anniversary of events to be pointed out. And some iconic images of people dancing on the Wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate. This kind of peaceful and daring involvement of the masses used to be called ‘people power’, combined with a temporary belief history had come good. ‘Wahnsinn’, indeed.

Recent Comments