Home » 2020

Yearly Archives: 2020

What’s the use of learning a language?

By Maria Scott, Associate Professor of French

Mastery of a second or third language can offer a huge advantage in life. Having an extra language at your disposal can be a passport to an interesting and well-paid job, to rewarding travels, and even to significant parts of your life spent in a foreign country. We know that language graduates are prized by employers, particularly if they have spent a year abroad during their studies, thereby demonstrating adaptability, resilience, and independence. We know that a degree in languages is a particular kind of Arts and Humanities degree that carries an employability turbo-charge: it teaches not just the very prized skill that is fluency in a foreign language, and the communicative and intercultural competence that accompanies this fluency, but also critical and analytical skills that are honed through intensive forays into disciplines such as literature, film, philosophy, linguistics, and art history. I have taught the French language to people who are now recognised specialists in French cinema, gender studies, Franco-Algerian history and literature, and contemporary French politics; these were all subjects that the individuals in question discovered as part of their undergraduate degrees in French. I have also taught French to students who went on to work in business, marketing, tourism, translation and interpreting, primary and secondary school teaching, and the law. These are only the graduates I know about.

However, this piece is not about the employability value of a degree in languages, but about a different kind of value, which is all the more precious because it is harder to pin down.

A few years ago, on international Francophonie day, I volunteered to visit my children’s primary school to speak about French language and culture and what they have meant to me. I went from classroom to classroom and talked about how learning French meant that I could now finally understand the television news in French, after having spent many frustrated evenings, many years ago, as a teenager straining, with my dad, to catch words and make sense of what was being said. The French language had taken me to Paris, where I had worked in a fast-food kitchen as a student one summer, and where I had later taught English at a university for nine months. The French language had also brought some dear friends into my life, both the living kind and the other kind, often long gone, that I got to know only through their writing. And learning the language had also given me a career, because I had been a university teacher of French for many years. With each of the class groups, I finished by saying that learning a language was like having an extension built in your brain: it gives you new ways of seeing and thinking about the world. I presented this as a self-evident truth; this truth was so much a part of my own lived experience that I had never really taken it out and examined it. But I remember the face of one Year 4 girl, clouded by concentration. She was trying very hard to understand. I asked if anyone had a question, and she raised her hand. She asked me if I could explain what I meant about the brain extension. I don’t remember what I answered. I do remember thinking that I needed to work on how to present this idea.

So here is my attempt to come up with an improved answer, in honour of that eight-year-old girl.

When we look at a potato, most of us will just see a potato. Most of us will know we can boil it, mash it, chip it, or roast it. If we know a lot about potatoes, we might be able to tell if it’s a King Edward or a Kerr’s Pink or a Jersey Royal. It probably wouldn’t occur to us, though, unless we have learned at least a smidgen of French, to think of a potato as an apple of the earth, une pomme de terre. And once we start to look at a potato as an earth apple, it becomes a little bit different from what we used to think it was. It might even occur to us that instead of mashing it or roasting it we could do as the French do, and slice it up and make a creamy gratin out of it, or dice it and sautée it in a frying pan with garlic and rosemary. Now imagine you have a whole other language in your head, and not just the French word for ‘spud’ and all the recipes that go with it. Think about how much richer your encounter with the world could be, how much more exciting and tasty, when you know more than one word for things, and more than one way to think about them.

I might tell the eight-year-old girl that sometimes it can be quite hard to change your ways of thinking about things. I remember crying bitter tears as a school exchange student in France, when on Easter Sunday, having been promised a chocolate egg by my host family, I was given something very different from what I had expected: a dark chocolate confection wrapped in impressively shiny layers, with, instead of sweets, a liqueur inside it that was deeply offensive to my fifteen-year-old taste buds. I’m afraid I had no idea how lucky I was. Sometimes we just want the thing we know and love, and don’t want the thing that’s different and unfamiliar. On the other hand, my enduring love of French mustard dates back to that exchange; I will always remember the first time I discovered it, around the table with my host family, conversation flying around too quickly for me to catch it, but that didn’t matter, because I was lost in a condiment-hazed world of my own. It was also around that dinner table, if memory serves, that I learned the phrase un ange passe, which means ‘an angel is passing’. This can be a very useful thing to say if you are ever in the middle of an animated conversation and an inexplicable silence suddenly descends. An angel strolling by is as good an explanation as any for such moments, and the idea tends to make people smile. We all need phrases like that sometimes.

I see one theme has emerged quite strongly in my argument for the brain-extending value of language learning: food. Perhaps this is to be expected, given that the French word for language (la langue) is also the French word for ‘tongue’; tongues are, after all, involved in tasting and eating as well as speaking. Also, as anyone who has ever visited the meat aisle of a French supermarket will attest, tongues (and brains) are themselves eminently edible in France. Maybe there is not, in the end, a big difference between learning a new tongue and learning to appreciate new food. Just as food is a sort of language, language is a sort of food. In fact, my favourite French poet, Charles Baudelaire, wrote about how the whole world was a kind of dictionary, made up of words and signs and images, which could be munched up and digested and transformed by the imagination. He was not wrong about much.

On the subject of things oral, a couple of years ago, at a talk with sixth-formers in the local comprehensive school, I was asked by one student why she should study a language when her actual plan was to become a dentist. What good would French, for example, ever be to her? Again, this question left me thinking afterwards. It is of course quite possible that the young woman in question would never have any practical need of a language other than English, and quite possible that she would never have any wish or need to relocate to another country. She might never encounter a client unable to communicate in English. It would probably not help her in any very concrete way to know that people who are ambitious are said, in French, to have long teeth, and that people with hard teeth are afflicted with what we, in English, would call a sharp tongue. She does not need to know that the roof of the mouth is un palais (which also means ‘palace’), or that a tongue, as we have established, is une langue. She may never need to know the various words and phrases in French that involve the French word for ‘mouth’, such as bouche bée (mouth agape) or faire la fine bouche (to turn your nose up at something), or bouche à oreille (word of mouth). She may never need to know that when a piece of news is on everyone’s lips in English, it’s already in everyone’s mouths in French (dans la bouche de tout le monde). And hopefully, for the sake of her clients, she will never have cause to ponder the mysterious reasons why the word bouche is contained in le boucher and la boucherie (the butcher’s). But being able to stay up to date with developments in the French-speaking dental world, or having the interest to read about how improvements in French dentristy caused a ‘smile revolution’ (Colin Jones) in the eighteenth century, or about why backstreet dentists in nineteenth-century France might have wanted to pay you for your teeth – well, these things would certainly help to liven up a routine check-up.

Learning a language has huge employability value, but it has another form of value too. I think my father knew this, even as he watched the French news programmes with my teenage self in a spirit of shared frustration. He knew at the time that he didn’t have long to live, so improving his French had little obvious use value, but he was absolutely intent on continuing to learn. My best answer (for now) to any young person wondering about the value of learning a language, even when she does not (for now) intend to make languages central to her choice of career, is that having another language up your sleeve can open up opportunities that you never knew were there, and can make life significantly more interesting and more fun. If nothing else, you may discover that studying a language can build a kind of extension in your brain. And who couldn’t do with a brain extension?

Aleksandr Pushkin’s Black History

Muireann Maguire, Senior Lecturer in Russian

It’s difficult to convey just how vital Aleksandr Pushkin (1799-1837) is to Russian culture. When explaining Pushkin to students or foreigners, Russians often say ‘Pushkin is our everything [nashe vse]’. Major public spaces like the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts and Pushkin Square, both in Moscow, emphasize the poet’s centrality; not far from the Kremlin and the offices of the famous news agency TASS, you can see statues of Pushkin and his bride Natalia Goncharova just beside the church where they married in 1831. In Russia’s second city, St. Petersburg, you’ll find the neoclassical Pushkin House, Russia’s main institute for literary research, where generations of Soviet and Russian scholars trained; you can visit the beautifully maintained apartment-museum near the Neva River which was Pushkin’s home for the last year of his life. Lines from Pushkin’s poems and plays are catchphrases in modern speech; more mundanely, if a job doesn’t get done, someone will ask, ‘Who’s going to do it? Pushkin?’ If something goes missing, the next question is, ‘Who took it? Pushkin?’ It’s a sly way to acknowledge the poet’s ubiquity: Pushkin really is ‘everything’ in spoken and written Russian. Although best known as a poet, he made every major literary genre his own (including lyric and narrative poetry, drama, the novel, the short story, even historical prose); he was instrumental in the development of literary Russian by skilfully combining the rhythms and structures of ordinary conversation with French-derived vocabulary and syntax to refresh and diversify his native language. Not only would Russian literature look very different without Pushkin; even its words would be poorer.

And yet – Pushkin was Black. Or as he phrased it in a note to Emperor Nicholas II of Russia in 1831, ‘no Russian man of letters except me can count a Negro [negr] among his ancestors’. Pushkin’s great-grandfather was a Black African, captured by slave traders in the region of present-day Cameroon, and sold in 1704 at the age of seven or eight to Russia’s inventive and ambitious Tsar Peter I, known as Peter the Great. Baptized Abram, he became Peter’s godson and protégé; he studied in Europe, mixed in French Enlightenment circles, trained as a military engineer, and died with the rank of general. Impressed by the career of the Carthaginian general Hannibal, Abram adopted his surname. He had two wives and eleven children. His granddaughter, Nadezhda Gannibal, known as ‘the beautiful Creole’, married into a minor but ancient noble family, the Pushkins. Her first son was Aleksandr Pushkin.

Pushkin was very conscious of his Black ancestry; his poems reveal fierce pride in and fascination with his heritage. Sometimes he lamented negative traits he associated with Black identity – usually ugliness or wildness – but he clearly valued the qualities of freedom and difference which he also saw as integral to Abram Gannibal. In 1827, aged twenty-eight, he began writing his great-grandfather’s biography, which he planned to call The Blackamoor of Peter the Great (Arap Petra Velikogo); Pushkin used the terms ‘Negro’ [negr] and ‘blackamoor’ [arap] interchangeably and without any sense of stigma. Pushkin never wrote more than seven chapters of the biography, and he published only the first two, much later, in 1834. His text shows remarkable sensitivity both to European spectators’ curiosity about the exotic ‘blackamoor’ in their midst and to Ibrahim’s awareness of their regard. Ibrahim (as Pushkin re-names his great-grandfather Abram in the book) is rarely appreciated for his personality; his performance of Blackness inevitably overshadows his identity.

‘Ibrahim’s arrival, his appearance, his education and his natural wit roused universal attention in Paris. All the ladies wanted to see le Nègre du czar at their receptions; the regent invited him more than once to his jolly evenings; he attended suppers enlivened by the youthful Voltaire and the aged Chaulieu, by the conversation of Montesquieu and Fontenelle; he missed not a single ball nor a single festivity, not one first performance, and he gave himself up to the whirlwind with all the ardour of his age and his race. [….] People usually regarded the young Negro [negr] as a wonder, surrounding him and showering him with greetings and questions, and this curiosity, although superficially well-disposed, offended his self-esteem. The sweet attention of women, perhaps the only goal of our strivings, not only failed to gladden his heart but even filled with sorrow and indignation. He felt that for them he was like some rare breed of beast, a unique creation, alien, accidentally brought into the world, having nothing in common with them. He even envied people whom nobody noticed, considering their insignificance to be good fortune.’

This extract from Chapter One demonstrates how clearly Pushkin empathized with what he perceived to have been his great-grandfather’s fate: public notoriety, private isolation. Pushkin’s own predicament was similar: he too felt isolated within his generation, and not merely because of the supposedly ‘African’ hair and facial features he had inherited. His vast talent, his awareness of that talent, his strong sense of social justice, and his equally strong sense of entitlement as a poet and as a Russian nobleman made him fiercely proud of who and what he was – without ever inuring him to the slanders and hypocrisies of everyday life. When a poetic rival, Faddei Bulgarin (here parodied by Pushkin as ‘Fiddlyarin’) mocked Abram Gannibal’s memory by suggesting that a drunken Peter the Great had bought him for a bottle of rum, the poet responded fiercely. (Bulgarin also slandered Pushkin’s mother by referring to her as a mulatka, or mulatto, a term Pushkin did find pejorative.) Pushkin wrote:

Fiddlyarin, sitting there at home,

Claims my black forebear Hannibal

Passed, for just one flask of rum,

Into the hands of some old salt.

Well, this old salt was that great captain

Who gave us fitting cause for pride,

Who gave, with mighty hand, our nation

An impulse not to be denied.

That captain loved my great-grandfather;

The purchased negro [arap], but no slave,

Grew up to highest ranking rather,

Tsar’s confidant, among the brave. (from ‘My Pedigree’, 1830)

Instead of apologizing for his ancestor’s Blackness, or trying to hide his time as a slave, Pushkin emphasizes both aspects to his family history. The ‘great captain’ is Tsar Peter the Great, and Abram Gannibal is the ‘purchased negro’ who rose to high status in Peter’s nation. Sadly, despite the inclusiveness of Soviet rhetoric on race, Russia’s engagement with Black nations and individuals since Pushkin’s time has been marred by Cold War power games and casual racism. Nonetheless the example of Pushkin – who is, after all, Russia’s ‘everything’ – reminds us that Black history is to be remembered, and celebrated, with pride.

To find out more about Pushkin’s short and tempestuous life, and why he became ‘our everything’, you could do worse than read Catriona Kelly’s Russian Literature: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2001), or for an even briefer explanation, I recommend the introduction to Antony Wood’s new Aleksandr Pushkin: Selected Poetry (Penguin Classics, 2020) – the extract above from ‘My Pedigree’ comes from this volume. The translation of a passage from Pushkin’s The Blackamoor of Peter the Great is my own.

Lettres noires. A post for Black History Month.

By Adam Watt, Head of the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures, Professor of French & Comparative Literature. His most recent book, as editor, is The Cambridge History of the Novel in French (forthcoming with Cambridge University Press, March 2021).

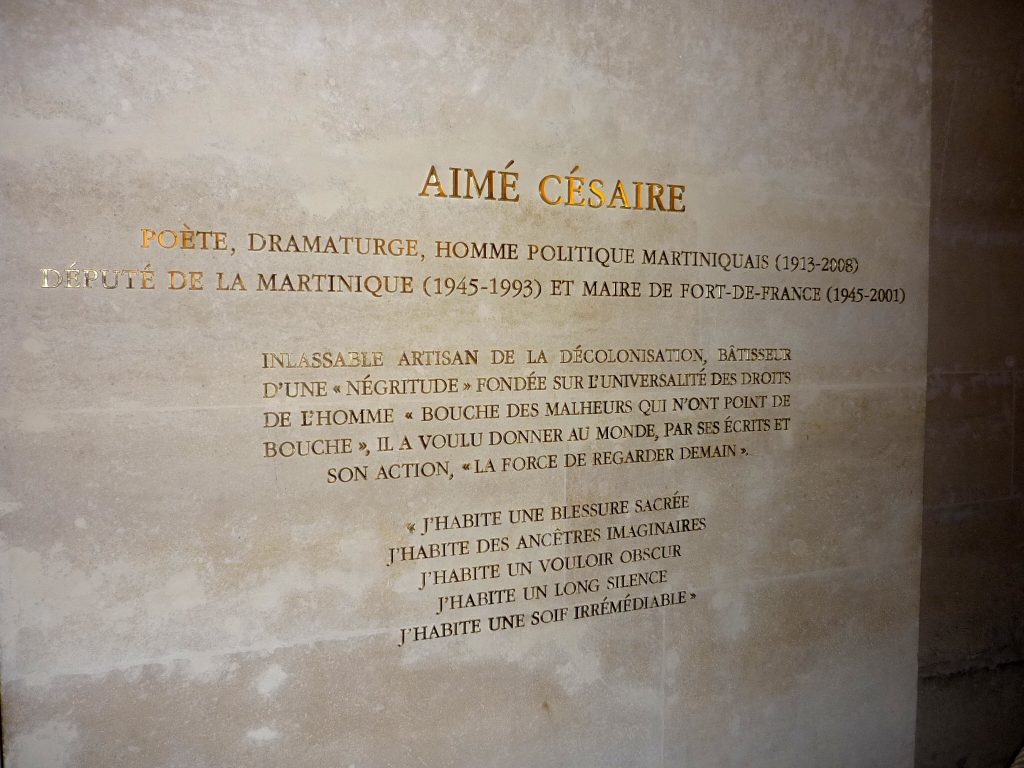

Jean Racine, Michel de Montaigne, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, Charles Baudelaire, Marcel Proust, Samuel Beckett. These are some of the authors I studied for the French part of my degree as a first-year undergraduate. They wrote in different periods, in different genres and were all challenging and interesting in their own ways. They were also all male, all white and all dead. Alongside them on the syllabus at the time, however, was a slim volume of poetry, which stood out from the other paperbacks I ordered in the summer before starting university: it was a different shape (almost square, like a school jotter, rather than uniformly rectangular like the others) and a sandy-orange colour, rather than the predominantly white and muted tones of the Folio, Flammarion and Minuit paperbacks. The book’s appearance wasn’t the only thing that was different about it. Its author was alive. And he was black.

Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, 1939) was the first and most celebrated work of the Martinican poet, intellectual and politician Aimé Césaire (1913-2008). My eighteen-year-old self was immediately confronted with a dimension of French culture and history of which until then I had had only a very vague awareness. My geography of mainland France was pretty good, but Martinique? Where was that? And how was it that they spoke French there? Suddenly it turned out that to study French wasn’t just to immerse myself in the plays, essays and novels of long-dead white males who lived and died in the Hexagon. It could also mean plunging into a rich, vibrant and unfamiliar world that I had never previously encountered. Césaire’s Cahier was poetry born of the first-hand experience of colonialism, written in a heady interweave of French and Creole on an island in the Caribbean, thousands of miles from the narrow, geographically limited ideas of ‘France’ and ‘Frenchness’ that I carried in my head at the time. This book was to be my first step in getting to grips with the history of the French colonial project, its impact and its legacies.

It’s a history I am still learning about, one whose imprint on French culture is immense. With the advent of Black History Month I wanted to take the opportunity to offer a few thoughts about some of the black writers that have shaped my understanding of the complexity and multifariousness that gets hidden or occluded by the awkward term ‘French literature’.

The last novel I read was La Cheffe: roman d’une cuisinière (The Cheffe: A Cook’s Novel, 2016) by a contemporary writer, Marie Ndiaye, who was born in Pithiviers, south of Paris, in 1967, to a French mother and a Senegalese father. Ndiaye is a major talent, who published her first novel aged seventeen and won the Prix Goncourt for her novel Trois femmes puissantes (Three Strong Women) in 2009. This work tells the stories of the lives of three women and explores ways in which they resist oppression and humiliation, and take action to live life on their own terms. (In some ways it anticipates structural and thematic aspects of Bernardine Evaristo’s brilliant Booker Prize winner, Girl, Woman, Other, published in 2019.) When Trois femmes puissantes won the Goncourt, this was only the third time that France’s most celebrated literary prize, established in 1903, had been won by a black writer. The first to do so was René Maran, born in Martinique to Guyanese parents, who won in 1921 with his first novel, Batouala; the second was the Martinican Patrick Chamoiseau for his novel Texaco in 1992.

La Cheffe tells of the story of a working class woman who begins as a cook for a wealthy family in provincial France and ends up with a Michelin star to her name as chef-proprietor of a celebrated restaurant in Bordeaux. The travails of the protagonist, a gifted, modest, single-minded woman, are retrospectively recounted by a quasi-obsessive male narrator. It’s a slow-moving tale, bleak in places, but the fraught gender dynamics are fascinating and the descriptions of food and the Cheffe’s attitude to it are wonderful.

Though not a feature of La Cheffe, Ndiaye’s relation to Senegal, the country of her father’s birth, which was under French rule from the late 18th century until 1960, is an important dimension of her writing. And many contemporary black authors and writers of colour working in French engage with similar and related questions of race, identity and belonging, often intertwined with wider considerations of culture, politics and ideology. Our first-years study Petit pays, a 2016 novel by Rwandan-French rapper-writer Gaël Faye, which explores the formative years of a young boy born to a French ex-patriate father and Rwandan refugee mother in Burundi, in the period leading up to the Rwandan genocide of 1994. (Burundi and Rwanda were under German, then Belgian colonial rule between the late nineteenth century and the mid-twentieth century). This work, which won the ‘Prix Goncourt des lycéens’ has had huge appeal globally and been translated into over thirty languages.

Another writer whose work repeatedly returns to the to-and-fro between France and a post-colonial ‘elsewhere’ is the French-Congolese novelist Alain Mabanckou. The Republic of Congo was a French sovereign state from 1880 until it gained independence in 1960. Mabanckou was born in Congo-Brazzaville in 1966, moved to France with a student scholarship in 1988 and published his first—simply breath-taking—novel Bleu-Blanc-Rouge in 1998. Mabanckou’s novels are full of humour and playfulness that surround frank and often deeply insightful appraisals of human foibles and fallibility. Bleu-Blanc-Rouge confronts us with the brutal reality of Paris as experienced by an African immigrant, a reality that contrasts with the idealised, fantastical notion of France as a sort of modern, Western paradise, as symbolised by the harmonious trio of colours in the French flag. The novel repeatedly confronts us with the problematic nature of constructions of France from elsewhere and the skewed, often prejudiced, metropolitan conceptions of ‘le pays’, the distant, enigmatic, even threatening African places of origin of those who come to France with hopes of a better life. Mabanckou’s works have been critically acclaimed and widely translated (see for instance the highly entertaining Verre cassé [Broken Glass, 2005], which takes us by the arm and hustles us into the chaotic, boozy world of the regulars at a Brazzaville bar). When he gave his inaugural lecture for the professorship to which he was elected at the Collège de France in 2016, Mabanckou’s telling title was ‘Lettres noires: des ténèbres à la lumière’, part of which I have borrowed for this post. You can watch the lecture here: https://www.college-de-france.fr/site/alain-mabanckou/inaugural-lecture-2016-03-17-18h00.htm

The last figure I would like to evoke is Gisèle Pineau, a prolific contemporary novelist born to Guadeloupian parents in Paris in 1956. Her novel of 1996, L’Exil selon Julia, is a fascinating autobiographical fiction, which renders the racism, prejudice and personal turmoil experienced by black citizens whose lives and identities are divided between France and a distant familial ‘home’, though the meaning and implications of this latter term are problematized throughout the book. The novel tells of a black Parisian-born girl and her Guadeloupian grandmother. Although both are French citizens (Guadeloupe has been ruled by the French since the eighteenth century) they both suffer abuse and struggle to be accepted. In Paris the young unnamed narrator isn’t French enough in the eyes of those around her and her grandmother is quaint, an oddity embodying racial and cultural otherness who is repeatedly scorned or pushed to the side. Visiting Guadeloupe, however, the narrator finds that she isn’t accepted there either: she is marked by her Parisian birth, too cosmopolitan, different. This summary may sound like Pineau’s book is gloomy or maudlin, though it is anything but: it evokes questions of identity, exile, displacement and what it means have a home, but it does so in a sprightly way, brimming with the energy and candour of its young narrator. Its descriptions of Paris and the Antilles are riveting, its accounts of racism both stark and deeply moving. Guadeloupe, like Martinique, is an overseas French region in the Caribbean, just under two hundred kilometres north-west of Césaire’s ‘pays natal’. It may be more familiar to British eighteen-year-olds today than Martinique was to my younger self, since Guadeloupe is the setting for the popular TV series Death in Paradise, starring, successively, Ben Miller, Kris Marshall and Ardal O’Hanlon. Guadeloupe is a world apart from metropolitan Paris, yet it, unlike the UK, is a part of the EU, so the rum cocktails are bought with euros and the school curricula in these islands follow the same patterns as those delivered in Grenoble or Limoges. The history that lies beneath this phenomenon, however, is much more troubling than the light-hearted focus of much of that TV series. French colonial interests in Senegal and the Republic of Congo and their presence in Guadeloupe and Martinique, were historically tied at root to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century trade in slaves and their exploitation in the colonies. A brief overview of this background can be found here: http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0097.

It would be misleading and short-sighted to lump together the work of writers like Pineau, Ndiaye and Mabanckou, somehow homogenizing their literary output by dint of the colour of their skin. Each of them explores different themes, takes different approaches to genre, and makes more or less explicit engagement with the wider literary culture that precedes them and which they in turn have shaped. To read, in particular, black women writers of French like Ndiaye and Pineau affords us extremely valuable intersectional insights into the combinatory impacts of race, class, gender and sexuality in the societies they depict. Reading is a vitally important formative activity for all of us, no matter our age, race or sexual orientation. It shapes our thinking, permits us a form of dialogue with others, gets us closer to their feelings and their fears; and it can grant us a means of access to the past. Reading gives us an opportunity to learn about the experiences of those who live or have lived their lives differently to us, who may look or think differently. ‘We cannot escape the legacies of the past’, writes Reni Eddo Lodge, ‘but we can use them to model our future.’ And if we choose our reading with some thought for who and what lies behind the pages in our hands, we start to do our bit, we start to model that future in positive ways.

‘Mark my words’: Using XML in Modern Languages research

By Edward Mills, part of the AHRC-funded ‘Learning French in Medieval England’ project team

The critical edition has been a central part of scholarship in the humanities for centuries. The primary output of an editing project remains the printed book, and staff in Modern Languages and Cultures at Exeter have been at the forefront of ensuring that primary material receives appropriate critical treatment and is made available to a wider audience: Hugh Roberts has recently collaborated on an edition of the Renaissance compilation, Les Muses incognues, while Jonathan Bradbury has recently edited the 17th-century Spanish Filósofo del aldea. This vital work is increasingly being supplemented by new technologies, which allow the text to be made available in a digital-first or digital-only format. Following several early success stories, among them the Electronic Beowulf project in 1993, increasing numbers of new editions have benefited from the greater interactivity, availability, and flexibility that ‘going digital’ can offer.

Here in Modern Languages and Cultures, we’re currently engaged in our own digital editing project, working to produce a new edition of an intriguing 13th-century rhymed French vocabulary known as the Tretiz. The most recent edition of the Tretiz is available online; however, its fairly inflexible PDF format means that it’s more accurate to describe it as a digitised edition, rather than as a digital one. In producing our own edition of the Tretiz, we want to give users the ability to compare two manuscripts side-by-side and make complex queries, which means that our edition will have to be built from the ground up as a digital-only (or, at least, digital-first) resource. In order to do that, we need to be able to make the text machine-readable: that is, make it possible for a computer to recognise elements of the text (such as topic divisions, glosses, and abbreviations) in the same way that humans can when we read a manuscript or print edition. This is where XML comes in.

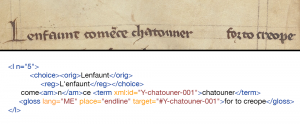

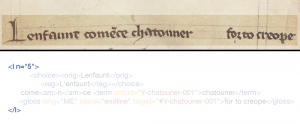

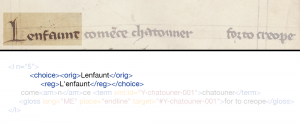

As we edit the Tretiz, we’re writing a form of code known as XML: eXtensible Markup Language. Some readers may feel XML looks quite a lot like HTML, the language that most webpages are written in; this is because both languages (XML and HTML) use a system of ‘tags’. Where XML differs, though, is that its tags don’t indicate how the document should look on a webpage, like HTML does. Instead of telling the computer to display text as ‘italic’ or ‘bold’, XML instead tells the computer what the material between tags actually is. By way of an example, let’s look at a line from one manuscript of the Tretiz: New Haven, Beinecke Library, MS Osborn a56. (This is line 5 of the text, and found on folio 1v, for those of you taking notes. The entire manuscript can be viewed online on the Beinecke Library’s website.)

Exactly how this would look in a print edition would depend on a whole set of transcription norms, but no-one would be too surprised to see something like this: ‘L’enfaunt comence chatouner’ (‘The child begins to crawl’). Now let’s take a look at that same line in our XML file:

You’d be forgiven for thinking that this looks as much like gibberish as a paragraph of text in French might to a non-French-speaker, and to an extent, you’d be right. XML may not be a ‘natural’ language in the same way as French or German, but like any language, it has its own grammar and rules, and these need to be followed in order to make the text comprehensible to its audience. The audience here, of course, is not human, but rather a computer; nevertheless, the need for grammatical accuracy – or, rather, ‘validity’ and ‘well-formedness’ – remains.

So, what does each bit of this language tell the computer? Let’s indulge in a spot of XML grammar …

Line numbers. The first and last parts of each line do what it says on the tin: namely, telling the computer that everything within them is a line. Just as natural languages have parts of speech, XML is built around ‘tags’, and everything is enclosed within tags – here, the <l> and </l> tags enclose a single line of text. The ‘n =5’ attribute, meanwhile, simply indicates that this is line 5 in our text.

Choices galore! Here we have what’s known as a ‘choice’ tag, one of the major benefits of a digital edition. It allows us to do something that print editions can’t do: specifically, encode two different versions of a text, which the reader will be able to switch between in the digital edition itself. While modern French punctuation requires the apostrophe to indicate elision in the noun phrase L’enfant (le + enfant), this wasn’t the case in medieval French script, and so the manuscript simply has Lenfaunt. The <choice> tag (within which we have further tags <orig> for ‘original’ and <reg> for ‘regularised’) saves us having to choose between fidelity to the manuscript and ease of reading: instead, we simply offer both, and let the reader choose what she or he wants to see.

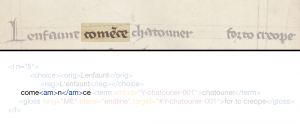

Abbreviations. This is perhaps the simplest part of the entire line, as the only tag is ‘abbreviation marker’ (<am>). This tag reflects the common practice in manuscripts of using a suite of abbreviations, including this one, known as the macron. In the ‘diplomatic’ version of our edition, the ‘n’ will be in italics; in the modernised version, it will simply appear normally.

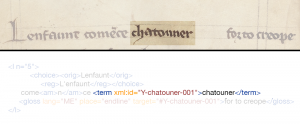

Text and gloss (1). One of the features that makes the Tretiz so exciting to edit is its frequent glossing of terms into Middle English. In our edition, we’re keen to highlight these glosses, so we’ve gone to the trouble of marking up any text that’s the subject of a gloss with a ‘term’ tag, as well as giving it a unique XML-id. Here, it’s ‘Y’ (the siglum or identifying letter for the manuscript), ‘chatouner’ (the word), and ‘001’ (its numbered occurrence in the text).

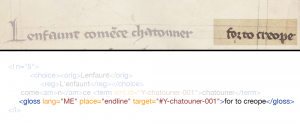

Text and gloss (2). The gloss to chatouner, ‘for to creope’ (to crawl), is the longest element in the line, but for good reason. We’re encoding plenty of information, which users of the digital edition will be able to interrogate: the language (Middle English), the place (at the end of the line, rather than above the French), and the precise term to which it refers.

We hope that this quick introduction to XML has given you a sense of some of the connections between modern languages and digital ones. If you’re interested in finding out more about the project, you can find us on Twitter at @medievalfrench, or visit our website. We hope to return to the Modern Languages blog before the end of the project, when we’ll update our readers on the trials and tribulations of all things encoding.

Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies at Exeter

Portuguese was celebrated throughout last week in many Portuguese-speaking countries as the 5th May has been officially proclaimed by UNESCO as the “World Portuguese language day”. Portuguese is one of the most widespread languages in the world with over 240 million speakers across eight countries and four continents. According to the United Nations, it is estimated that in 2050 the number of speakers will rise to nearly 400 million. Celebrating Portuguese means celebrating cultural diversity and multilingualism. It is also a moment of critical reflection on the shared (and often troubled) histories and on the complexities of the use of Portuguese, which has, over time, coexisted, displaced and mixed with other languages. It is against this backdrop that we also celebrate Portuguese at the University of Exeter precisely in the same spirit; studying Portuguese at Exeter goes beyond the understanding of the language and the associated diverse cultures within the boundaries of the nation-state and embraces the wider Portuguese-speaking space and its complex relations.

Portuguese Studies at Exeter was launched as a programme in 2014. Even though students at Exeter could learn Portuguese language up to intermediate level as part of the BA in Spanish, 2014 saw the first cohort of students in Modern Languages and Cultures who would successfully graduate in 2018. These students and the following cohorts of students acquired more than the two standardised varieties of Portuguese (European and Brazilian Portuguese) up to advanced level; they also engaged, through literature, film and linguistics, with the multiple realities, identities, cultures and the intertwined histories that have had a profound impact, still visible today, on the societies and cultures as well on the linguistic make-up of the Portuguese-speaking world. For most of them, the Luso-Afro-Brazilian Studies was completely uncharted territory.

The year abroad (YA) is a turning point. Exeter has a student exchange scheme with partner universities in Portugal (University of Porto and the University of Coimbra) and Brazil (UFCB – Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis). Many students have also taken up working placements in Portugal (e.g. law firms, translation companies) and in Brazil (e.g. translation and proof-reading companies, working for NGOs and charities). Upon their return, they have honed their linguistic skills, speaking very distinctively either European or Brazilian Portuguese, some of them at a near-native level (see one of our 2019-20 finalists talking about his studies, the university and the city). Being a small unit offers the experience of a tight-knit community of students in which, for example, students on their YA, via video link, and final-year students share their YA experiences with second-year students.

After the YA, some students have opted to write a dissertation, deepening their knowledge on some aspects of the Portuguese-speaking world, for example on postcolonial varieties of Portuguese, Cuban-Angolan relations and the impact of the Angolan civil war in the second generation presented in literature vs. official narratives, the Tropicália movement in Brazil, the representation of the favela in film.

In these uncertain times, there’s a real urgency to train the current generation of students to think beyond national boundaries, beyond a monolithic view of language, and to think about the world from an alternative paradigm to the European, white, male-dominated discourse. This is at the core of the Luso-Afro-Brazilian studies at Exeter and of our commitment to current and future generations of students of Portuguese.

Nature and Culture: Environmental matters in Latin American Film

After filmmaker Jorge Bodansky’s visit to Exeter and the screening of his landmark film Iracema, Dr Natália Pinazza, Lecturer in Portuguese in the department of Modern Languages & Cultures, writes about films set in the Amazon Rainforest.

On the 5th February, the Exeter Centre for Latin American Studies (EXCELAS) hosted an event with renowned Brazilian filmmaker Jorge Bodansky with a screening of his landmark film Iracema, Uma Transa Amazônica (Iracema, 1974) and presentation of his latest project Mercúrio. Bodansky talked to staff and students about his work on the Amazon Rainforest, which raised some issues that I will address in this post.

Iracema, Uma Transa Amazônica by Bodanzky and Orlando Senna is set during the construction of the Trans-Amazon Highway, which caused deforestation of the Amazon region and exposed indigenous populations to outsiders. Iracema inhabits an interstitial space between fictive construct and documentary. It overtly and consciously subverts the well-known iconography of the road movie genre, which consists of symbols of modernity such as highways and motor vehicles, when trying to problematise western notions of progress.

Iracema does not fail to ridicule the “civilised” positivist discourses behind the capitalist exploitation of nature. At the beginning of the film the truck driver, who introduces himself as Tião Brasil Grande (translated as “Sebastian Great Brazil”) dismisses indigenous approaches to the environment by claiming that “nature is the road” (a natureza é a estrada). This is clear when Tião relates the Trans-Amazon Project with development, by claiming “this place is improving, they are now building roads here”. For the indigenous female character, on the other hand, being on the road means prostituting herself. The film engages with a neocolonial critique where the highway prompts the circulation of commodities and investment of capital.

In Brazil a number of initiatives to promote indigenous expression through cinema have been taken by the Secretary of Identity and Diversity of the Brazilian Cultural Ministry. Amongst the projects that have significantly changed the situation in Brazil through indigenous media literacy, “vídeo na aldeia” stands out. The project consists of a group of filmmakers that provide indigenous communities with workshops so they can produce their own films. Initiatives like “vídeo na aldeia” often receive international support and encouragement, primarily due to the UNESCO 2005 convention on Diversity of Cultural Expressions. However, the representation of the original inhabitants of Brazil is often discussed in relation to the motif of encounter between European and indigenous people and their subsequent resistance to domination, which was installed by the colonisers and perpetuated by Brazilian society. This motif is explored in my second-year module “Travelling Identities in the Lusophone World”. https://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/modernlanguages/modules/MLP2005/description/

Iracema, a reference to José de Alencar’s classic Indianist romance Iracema (1865) is another film that evokes the relationship of a European, in this case a white lorry driver, and an indigene. This preoccupation with indigenous and environmental issues comes into play in other films including At Play in the Fields of the Lord (1989) and, more recently, Serras da Desordem. The film, however, updates the figure of both the coloniser and colonised to the 20th century so as to explore the perpetuation of colonial structures that keep the indigenous subservient. This approach is also adopted by Ajuricaba (1977). The traditional romance between European and indigene, which uses miscegenation as a metaphor for the foundation of Brazil, is subverted in Brava Gente Brasileira (2000). The film shows seduction by the indigene, who has some agency in the film, as a weapon to be used against the European coloniser.

An increasing number of Brazilian, and more generally Latin American, films have adopted the format of the road movie since Iracema. In previous publications, I have focused on how the leap to prominence of the Latin American road movie within film studies over the past five years has testified to the rethinking of the road movie as a global film category instead of a quintessentially US genre. Such a reframing foregrounds the diversity of Latin American road movies and their contribution to global film production, and refutes the notion that these films are mere attempts to copy Hollywood. Clearly, treating film production from different parts of the world as Hollywood’s “other” is not a problem exclusive to the road movie genre or Latin American cinema.

A recent example of a Latin American road movie set in the Amazon is Embrace of the Serpent (El Abrazo de la serpiente, 2015) by Colombian filmmaker Ciro Guerra. Embrace of the Serpent uses journeys to denounce historical colonialism and engage with more contemporary and global discourses on eco-criticism. Embrace of the Serpent’s narrative trajectory is shaped by the bewildering journey across the Amazon, undertaken by a shaman and two different scientists, each in search of a rare sacred plant, at different moments set 30 years apart. This defining feature of the genre was central to analysing Embrace of the Serpent’s postcolonial critique through its refusal of the road. In its refusal of the linearity of both the road and western storytelling, Embrace of the Serpent adheres to a strongly global agenda because the experience of violence and inequality as colonial legacies not only present an insurmountable obstacle for the region’s development but also a disaster for humanity.

Recent Comments