Adam Watt, Head of Modern Languages & Cultures

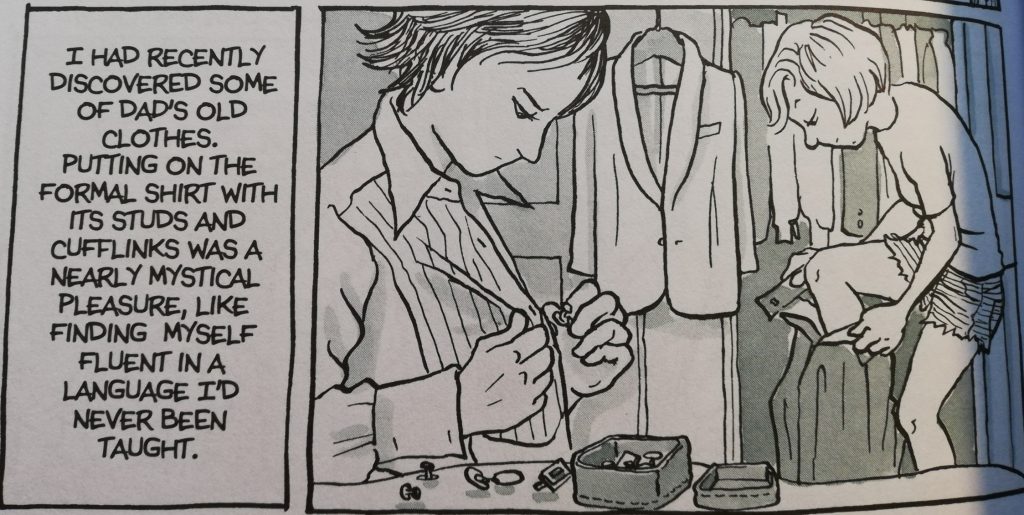

‘I had recently discovered some of dad’s old clothes. Putting on the formal shirt with its studs and cufflinks was a nearly mystical pleasure, like finding myself fluent in a language I’d never been taught.’

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (Jonathan Cape, 2006), p. 182

Putting on someone else’s clothes brings a certain frisson: of intrigue, intimacy, comparison, transgression. In the lines quoted above, Alison Bechdel highlights the extraordinary transformative potential of something as ordinary as a shirt. Characteristically for Bechdel, her chosen image here is rooted in words that let us make up a world: the little girl pulling on her father’s shirt experiences something almost spiritual (‘a near mystical pleasure’), equivalent to being suddenly proficient in another language, but without the hard slog of learning it. In Bechdel’s two sentences we find a neat encapsulation of the theme for this year’s LGBT+ History Month: ‘Mind, Body and Spirit’. While some of us may have little truck with spirituality, or perhaps only very rare encounters with it, none of us can avoid entanglement in those other terms: mind and body. We are all, inescapably, embodied, carnal beings. Within and connected to our body is our brain. A sentient scaffolding of bone and muscle, ligament, tendon and all the other messy parts inside, holds up a hugely powerful data processing unit. We live, mostly, in the bodies we are born with: they age, mature, sometimes get modified or injured, carry children, give birth, are sites of pain as well as pleasure. One of the struggles of embodied life, as Katharina Volckmer has it in her recent novel about sex and gender identity, The Appointment, is that ‘the body others see is never the body we see’ (Fitzcarraldo, 2020, p. 58). Pulling on someone else’s shirt, however, covering and othering our body, can be liberating, invigorating, illuminating.

Bechdel’s image of mind and body here is intriguing since it intersects in a number of interesting ways with a moment in Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913-1927), a novel that has an important place in the exploration of identity and sexuality we find in Fun Home (more on this below). In Le Côté de Guermantes, the third volume of Proust’s novel, his narrator reflects on the superficiality of the social world he now inhabits – one he long dreamt of, yet which transpires to be less inspiring than he had envisaged. He describes his ‘vie intérieure’ (inner life) as being dormant during a dinner party whilst the guests around him tell their boring stories. He qualifies this experience as:

ces heures mondaines où j’habitais mon épiderme, mes cheveux bien coiffés, mon plastron de chemise, c’est-à-dire où je ne pouvais rien éprouver de ce qui était pour moi, dans la vie, le plaisir. (A la recherche du temps perdu, ed. by Tadié et al, 4 vols, Gallimard 1987-89, II, p. 817)

those hours [during which] I lived on the surface, my hair well brushed, my shirt-front starched, in which, that is to say, I could feel nothing of what constituted for me the pleasure of life. (The Guermantes Way, trans. Scott Moncrieff/Kilmartin, rev. Enright, Vintage, 1996, p. 610)

Here the dress shirt, worn by its rightful owner, is a deadener of sensation, with its starched front (‘plastron’) a symbolic barrier to pleasure and the vital spark of the inner life. While the borrowed shirt offered a mystical pleasure and a new, queer fluency of connection between body and mind, the shirt worn as the conventional uniform of the worldly socialite shuts down any such possibility.

Bechdel’s book is a graphic novel about family and sexual identity. Fun Home is beautifully crafted, wickedly funny and often very moving. With the story of her narrator Alison’s father’s mostly hidden homosexuality and its impact on his life and family, Bechdel interweaves an account of Alison’s growing up and coming out as gay shortly after leaving home for college. After she comes out to her parents in a letter (it’s 1979), her mother reveals that her father has had affairs with other men. Shortly after, he dies in a road traffic accident that may or may not have been suicide. The book is an account of the narrator’s loss of her father, the process of her self-becoming and the ways in which her self-acceptance as a lesbian is intertwined with her father’s long denied sexual identity. The ‘fun home’ of the title is the family’s shorthand for the funeral home run by the father alongside his job as a high-school English teacher. As such, bodies—the dynamic, lively bodies of Alison and her family and the lifeless cadavers of the recently departed who arrive at the ‘fun home’ for pre-funeral preparation—pepper the panels and spreads of Bechdel’s book. Alison’s body develops and through it she starts to learn the confusing lessons of human sexuality. Spliced, like the strands of a rope, with these embodied discoveries are the explorations and encounters of the narrator’s queer, bookish and inquisitive mind. Bechdel repeatedly shows how we use the books we read to come to terms with who we are and to understand those around us. Much of Alison’s life experience—her joys and bewilderments and a good measure of her gradual unravelling of the mystery of her father’s enigmatic character and habits—comes filtered through reading and thinking about books that are read or encountered. There are brilliant reflections here on Henry James, Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde, on James Joyce, Colette, Albert Camus and Kate Millett. Though Bechdel doesn’t say so, we might argue that reading literature (including Bechdel’s Fun Home, of course) is like pulling on someone else’s shirt. It allows us, after a fashion, to leave our body and our often troubled relation to it in order—in the safe and unregulated precincts of our mind—to explore the minds and bodies of others.

This may be one of the strongest arguments in favour of reading fiction: it gives readers access, of a sort, to the experiences of others. (Something argued eloquently in a recent book by my distinguished colleague Maria Scott – see here.) Whatever our sexual orientation, when we read Fun Home, or Alan Hollinghurst’s The Folding Star, or Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, or Colette’s Claudine novels they offer us that chance to immerse ourselves, after a fashion, in gay, queer or bi experience. In his recent memoir the novelist and critic Edmund White notes something similar. ‘Fiction’, he argues, is an ‘artform that places us in the mind of a perceiver. That is its great gift’ (The Unpunished Vice, Bloomsbury, 2018, p. 89). Access to the minds of others may well be fiction’s greatest gift and it’s one we should accept—and indeed seek out—with humility and openness. Reading texts ‘about’ or rooted in LGBT+ experience can change minds, inform minds, provide succour and solace, reassurance and resolve to body and spirit. If we want to enrich our lives and contribute to making our society a place of acceptance and understanding, even though it might not fit, it might feel awkward or unfamiliar, we need to put on that shirt.

Recent Comments