Black History along Berlin’s Under- and Overground Network

In the 1920s, Black avant-garde dancer Josephine Baker enchanted not just the likes of Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway and Max Reinhardt but the wider public, including that of Berlin. A few years later, in August 1936, Jesse Owens thrilled the audience attending Berlin’s Olympic Games with his record-breaking performances. These are well-recorded biographical snapshots. Both celebrities paid only fleeting visits to the country: Baker’s home was in France; Jesse Owens returned with the rest of the team to the United States. Meanwhile, some of Germany’s lesser-known Black History can be traced through Berlin’s public transport system – telling stories of daily, no less extraordinary lives over several centuries.

I owe my first example to a Final Year student who referred to it during an oral exam in 2020. He expressed astonishment at his discovery of the quarter around ‘Afrikanische Straße’ while on his way to attend a sports training session. Berlin’s underground line number 6 connects Alt-Tegel in the northwest of the city with Alt-Mariendorf in the south – ‘Alt’ indicates former villages outside the city boundaries. During the Cold War, five out of overall 29 stops along this line were so-called ghost-stations in German Democratic Republic territory. Here, trains would slowly pass through the eerie darkness without stopping. This may be one reason why few of us took much notice of ‘Afrikanische Straße’: you hardly ever travelled this route without a reason. ‘Afrikanische Straße’ reflects that the street-names in the surrounding area are based on Germany’s colonial past: Swakopmund, Ghana, Togo, Windhuk, Kamerun and Sansibar mark the ambitions of the German Empire between 1871 and 1918. Initiatives to replace some of the names have taken a long time to materialize.

These references to Germany’s former colonies are also linked to merchant Carl Hagenbeck (1844-1913). He made his name trading wild animals and promoting zoos with more natural settings. Hagenbeck had ambitious plans for Berlin too. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, large zoos were not simply concerned with exotic animals. Instead, what appealed to visitors, including those of world fairs, were the so-called ‘living villages’ for ‘empirical study and education’. The German term ‘Völkerschau’ translates as ‘observing peoples’ – including their performances of dances and ‘typical’ rituals during opening hours. In Through the Lion Gate Gary Bruce has detailed some of the heart-breaking practices in Berlin where the most popular exhibits included people from

Lapland, Egypt and Cameroon.

Travel further southeast and, not far from the Brandenburg Gate, one encounters ‘Mohrenstraße’ on line 2. The badly war-damaged station on GDR territory was re-opened in 1950. After several name-changes in praise of German communists (Ernst Thälman, Otto Grotewohl) in 1991, following German Unification, the station’s name became Mohrenstraße. At that point, an urban myth about Mohrenstraße overshadowed everything else: rumour had it, that the spectacular marble inside the station stemmed from Hitler’s Chancellery – sending chills down one’s spine while passing through the station and marking a highlight for visitors touring Berlin. Alas, the marble was prepared after the war.

There is some speculation how the name of the nearby street Mohrenstraße came about – it may refer to slaves, former black residents or an African delegation, all can be linked to the 17th century. In fact, the archaic reference to ‘Moors’ dates back to the 16th century and was, usually, associated with Black Africans. To this day, one finds – in particular in Austria and Southern Germany – pharmacies and restaurants ‘Zum Mohren’; the practice to associate select chocolates and cakes with the term has stopped. Berlin’s Mohrenstraße caused repeated debates. In 2020, the murder of George Floyd renewed the interest in the name of the station. After the choice of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka had to be dismissed as a new name, the decision fell on Anton Wilhelm Amo who represents yet another layer of Germany’s Black History.

There is some speculation how the name of the nearby street Mohrenstraße came about – it may refer to slaves, former black residents or an African delegation, all can be linked to the 17th century. In fact, the archaic reference to ‘Moors’ dates back to the 16th century and was, usually, associated with Black Africans. To this day, one finds – in particular in Austria and Southern Germany – pharmacies and restaurants ‘Zum Mohren’; the practice to associate select chocolates and cakes with the term has stopped. Berlin’s Mohrenstraße caused repeated debates. In 2020, the murder of George Floyd renewed the interest in the name of the station. After the choice of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka had to be dismissed as a new name, the decision fell on Anton Wilhelm Amo who represents yet another layer of Germany’s Black History.

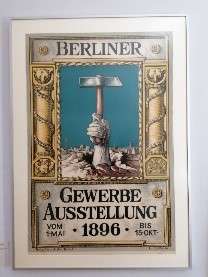

Travelling on (by now over-ground) towards Berlin’s south eastern suburbs, the local museum in Treptow (https://www.museumsportal-berlin.de/en/museums/museum-treptow/) provides an exemplary approach to Germany’s colonial past. Together with other museums and the Initiative Black People in Germany and Berlin Postkolonial, in 2017 Treptow housed a small and powerful exhibition based on the Berlin Trade Exhibition (Gewerbeausstellung) of 1896. In 2021, ‘zurückgeschaut / looking back’ (in cooperation with Dekoloniale Memory Culture in the City) expands the original approach.

The Trade Exhibition of 1896 attempted to emphasize German commercial and scientific achievements and to affirm the role of the relatively new German capital of Berlin. To visualize the message, Germany’s presumed modernity was set against the exotic ‘natives’ villages’ organized for the occasion. This part of the Gewerbeausstellung ‘aimed to create the greatest possible difference between the population of the “cosmopolitan city” with its alleged “refined customs” and “proud splendour” and the colonised people who would supposedly bring an element of “natural wilderness” and “rawest culture” to the banks of the Spree river.’ One of the exhibition rooms displays the photographs of those who had been lured to Berlin – their work contracts had not clarified that they would be exhibited. While most returned home once the Gewerbeausstellung had closed, twenty stayed, married and had children.

The Trade Exhibition of 1896 attempted to emphasize German commercial and scientific achievements and to affirm the role of the relatively new German capital of Berlin. To visualize the message, Germany’s presumed modernity was set against the exotic ‘natives’ villages’ organized for the occasion. This part of the Gewerbeausstellung ‘aimed to create the greatest possible difference between the population of the “cosmopolitan city” with its alleged “refined customs” and “proud splendour” and the colonised people who would supposedly bring an element of “natural wilderness” and “rawest culture” to the banks of the Spree river.’ One of the exhibition rooms displays the photographs of those who had been lured to Berlin – their work contracts had not clarified that they would be exhibited. While most returned home once the Gewerbeausstellung had closed, twenty stayed, married and had children.

By the 1920s, Berlin had become a cosmopolitan metropolis. In 1927, the German communist Willi Münzenberg took actively part in the ‘First Congress against Colonial Repression and Imperialism’, followed in 1930 by the ‘International Conference of Negro Workers’ in Hamburg. In Berlin, a new underground station in the south west of the city was named Onkel Toms Hütte / Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1929 in reference to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel of 1852. The station provided the modernist housing estate of the same name with access to the city-centre.

However, by the 1930s Germany’s history caught up with some of the children of those who had remained in the country. Martha Ndumbe, daughter of Duala Jacob Njo Ndumbe, died in Ravensbrück concentration camp on 5 February 1944. Josefa van der Want, a Black German dancer and daughter of Josef Bohinge Boholle, died in 1955 ‘from the late effects of the imprisonment in a concentration camp’. Meanwhile, Josephine Baker, the celebrated star of 1920s Berlin, joined the French Resistance against the German occupiers during the Second World War and earned the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance.

After the Second World War, with the occupation and division of Germany a new, at times no less challenging chapter for Black History in the country started. Today, about 1 Million Afro-Germans or Black Germans are resident in Germany, predominantly in large cities, including Berlin.

Recent Comments