Marking thirty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall

It is thirty years to the day since the broaching of the Berlin Wall. Ulrike Zitzlsperger, Associate Professor of German in the department of Modern Languages, reflects on her first-hand experience of the events and her teaching and research in this area in the years since 1989.

*****

On 9 November 2019 Berlin is once more the central location for celebrations commemorating the fall of the Wall, the physical divide between East and West Germany and unique symbol of the Cold War. In 2019 the Wall will have been gone for more years than it actually stood.

Developed from August 1961 to stem the growing exodus of a skilled work-force, the Wall allowed the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to become the success story of the Warsaw Pact. However, time and again people risked everything to escape to the West. Even if they were successful they left their former lives behind and knew that any remaining family would be punished by the state: costing them, for example, that much longed-for place to study at University or a trip abroad. There were more sinister options too. In Berlin, so-called frontier-city of the Cold War, the Wall encircled the Western part of the city, measuring between 3.4 and 4.2 metres in height. There is a memorable scene in Steven Spielberg’s film Bridge of Spies (2015), when one of the protagonists watches lone figures from the inner-city railway desperately climbing the Wall. The scene is fiction – just like the scene in the Alfred Hitchcock film Torn Curtain (1966) that makes us believe that GDR citizens hijacked buses with passengers on board to escape. The Wall never needed this kind of embellishment: it was sufficiently surreal, monstrous and overwhelming as it was, including the death-strip in between both Walls – one facing West, one East.

The build-up to the actual fall of the Berlin Wall had been steady: months of reports about people from East Germany leaving everything behind to move to the West while on ‘holiday’ in Hungary, occupied embassies, and thousands joining demonstrations in Leipzig and other cities. In the West and in particular in West Berlin we were glued to our television screens. Nonetheless, when the news broke that the border opened that night a sense of disbelief dominated. After all, we had grown up with the divide between East and West and learned about it in our history books at school. To us the Wall seemed permanent. In the event, happy speechlessness found a fitting expression: ‘Wahnsinn’, translating as ‘unbelievable, sheer madness’, though of course this sensation was utterly positive. It became the word of the year 1989.

Even more exciting than claiming pieces from the Wall that night was venturing through one of the newly opened crossing points towards Alexanderplatz in the East – against the tide of East Berliners coming to West Berlin. More than breaking pieces out of the Wall, this tentative, equally nervous and excited walk down a deserted road in ‘the other’ Germany provided us with a sense that no matter what we were experiencing history in the making.

In the months to come therafter, life in Berlin was sensationally exciting: we explored the East, the East explored the West (to a degree), while the city itself transformed before our eyes.

When I first taught the history of Berlin at Exeter people remembered the events of 1989 first hand. Some had heard pilots making announcements during a flight, others saw events unfold on television, and some had paid a fortune to come to Berlin. Among the first seminar group I taught was even a mature student who had been a pilot during the Berlin Airlift of 1948-49. The events of 1989 took centre-stage – as did the measures taken to determine how the divided city would be reunified: again, history in the making, right in front of our eyes.

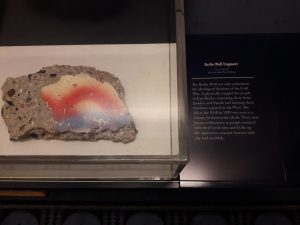

As time went by though, more and more of what had seemed all-important detail turned into footnotes: the story of the fall of the Berlin Wall became shorter and more concise, in teaching as much as in research. At one point, participants in a Berlin seminar had been born in 1989. And while it was a straightforward matter to explain why the Berlin Wall had been built, it became increasingly challenging to explain what it really looked like and why it was so hard to overcome it. Over time interests shifted: for a few years memory studies boomed. What was most interesting were the ‘competing memories’: whose story was it? The East’s, the West’s, or was a more international perspective possibly best? Is the Wall best remembered where it had stood – or in one of those places where the consequences could be felt: such as former prisons or transition camps for emigrants and refugees? Today Berlin is dotted with Wall remnants, even though many pieces were gifted to other states, sold or destroyed.

Berlin has turned into a number one tourist destination: history, and in particular history with a happy ending, sells. The numerous souvenirs are proof of that – few deal with the ‘real’ Wall, many focus on the Wall’s fall. Some look like the result of a 30 seconds brainstorming exercise. Examples include fridge magnets that show the East German car, the Trabi, breaking through the Wall (never!) and the graffiti that was only to be found on the West-facing Wall from the 1980s onwards (but not the collection of buzz words shown here). The recipe is simple: the Wall as a symbol, the Trabi as a nod towards daily life in the East, and graffiti to mark ‘cool’ Berlin, now proudly branded as ‘city of freedom’.

The current anniversary stands out for two reasons: the symbolism of the Berlin Wall at a time when new walls and borders are developed is more important than ever before. And quite possibly this is the last time witnesses are coming to the fore with the German and the international media showing such a keen interest: witnesses in the shape of those who lived with the Wall, those who saw its demise and then all those who were born since and who have heard about the Wall second hand. The actual Wall has moved to heritage sites and into museums – its original pieces serve as case studies in exhibitions: for example in Canberra in December 2018 in a display about democracy.

From here on the Wall is material for the history books again: a few facts and maps to be learnt by heart, the odd future anniversary of events to be pointed out. And some iconic images of people dancing on the Wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate. This kind of peaceful and daring involvement of the masses used to be called ‘people power’, combined with a temporary belief history had come good. ‘Wahnsinn’, indeed.

Celebrating Black History Month

To get our blog going, and to celebrate Black History Month, Senior Lecturer in Portuguese and AHRC Leadership Fellow Ana Martins writes about her current research project.

The “Women of the Brown Atlantic” project: visions of the impossible

I’ve always felt slightly anxious in Brazil, as if I had arrived there too early, knowing too little, feeling too much (guilt? fear? love?). The trips started during my PhD at the University of Manchester, which was dedicated to studying Lusophone African literature alongside Portuguese literature. One thing I remember from those years is the flow of African-centred material, both in Portuguese and in translation, that came from Brazilian academia. It was (and continues to be) overwhelming. I soon realised that one had to travel there, attend conferences, meet experts and fellow students, writers and poets, because Brazil was completely unavoidable if you were researching Lusophone Africa.

Portugal was important too, but in another, less urgent way. Going to Brazil to discuss Lusophone African cultures and literatures was very much like trying to look in three different directions simultaneously. It was often intellectually stimulating, and certainly extenuating. I had first noticed Brazilian constructions of blackness, brownness and whiteness back in Portugal, through popular culture and telenovelas, but this was the first time I was experiencing these being projected onto me, a white Portuguese young student who knew way less than she thought.

In my first visit to Brazil, back in 2006, I, like many tourists, stopped in the street and bought a painting from a black street artist, Vitorino, which now adorns my office wall. The work depicts a bahiana woman sitting down on a stool, her head and torso turned to the left. Next to her is what I later learned to recognise as a tabuleiro filled with acarajés. At the time, I didn’t know that eight years onwards I would be writing about this very Afro-Bahian street-food, and that the project would lead me to conceive of another project on memory and mobility in the Brown Atlantic. The flight from Lusophone African literature, the subject of my PhD thesis, was already on its way. It began with the buying of this painting.

I can see it now, how the act of buying reified my own whiteness in Brazil, directing my research in certain ways at the expense of others. As I witnessed, in the Brazilian conference halls, what I often perceived as the idealisation of Africa and its re-inscription on the body through clothes, jewellery, hairstyles, music, and food, I experienced my own Portuguese whiteness on the street as a reified experience. Or better put, I experienced myself reifying my whiteness with my habits, my purchases. Me witnessing my whiteness take up space before me, filling my luggage in the airports of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, and later Salvador da Bahia, Santa Catarina, Minas Gerais.

I can see it now, how the act of buying reified my own whiteness in Brazil, directing my research in certain ways at the expense of others. As I witnessed, in the Brazilian conference halls, what I often perceived as the idealisation of Africa and its re-inscription on the body through clothes, jewellery, hairstyles, music, and food, I experienced my own Portuguese whiteness on the street as a reified experience. Or better put, I experienced myself reifying my whiteness with my habits, my purchases. Me witnessing my whiteness take up space before me, filling my luggage in the airports of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, and later Salvador da Bahia, Santa Catarina, Minas Gerais.

I would not want “Women of the Brown Atlantic,” the new project driving my research, to take off without being calibrated by these reflections, because it is, in many ways, the culmination of my early journeys through the Brown (and Black) Atlantic(s) – Portugal, UK, Brazil, Mozambique, USA, Italy – ten years of travelling, crossing borders, meeting people, learning and (mostly) unlearning about black and white histories, trying to work out how to write, how to be a feminist, how to think about this world’s (neo)colonialism, racism and sexism, how to talk about Africa (which eventually became the title of one of my undergraduate second year modules!), how to engage with Brazil, and finally, how to look at Portugal afresh.

“Women of the Brown Atlantic: Real and Imaginary Passages in Portuguese 1711-2011” is a project concerned with the (in)visibility of black female mobility and memory in the Brown (i.e., Portuguese speaking) Atlantic. One way in which it encourages new engagements with black history is by questioning the usefulness of the image of the archive as a universalised metaphor for the storage of memory. Is the archive metaphor adequate to theorise black female memory of the Brown Atlantic? If this memory is grounded in the invisibility/silencing of black women, is it adequate as a universalised memory metaphor per se?

With these two questions, the project aims to revise the use of the archive metaphor, and its historical complicity with the maritime, from the specific viewpoint of Lusophone black women and white men’s engagement with remembering as a creative process. The notion of memory as archival is often permeated with assumptions about (maritime) archives as neutral storehouses that hold the past and future and are thus able to mobilise a totalising interpretation of the past. However, as record keeping systems, archives are not neutral, but active storehouses where power is negotiated, contested and confirmed. “Women of the Brown Atlantic” develops a new framework for claiming under-theorised gendered and queer memory sites of the Brown Atlantic by introducing the potentially field-changing metaphor of the rainbow, derived from an Afro-Brazilian popular saying: “if you walk under the rainbow, you run the risk of changing your sex.”

In Brazil, the image of the rainbow is tendentiously associated with Orishá Oxumaré, the male-female snake-like God of movements and cycles in the Candomblé Afro-Brazilian religion (Verger 2002), who holds the power to change people’s sex. This project takes Oxumaré’s symbol, the rainbow, arguably queerer than the rainbow flag of the LGBT movement, so as to revise the use of the archive metaphor and its historical complicity with the maritime.

I draw on established Afro-Brazilian writers (Carolina Maria de Jesus, Conceição Evaristo, Ana Maria Gonçalves, among others), all of whom have engaged with Oxumaré’s symbol in order to write about and remember pasts of slavery and poverty, but also to discern where their hopes and desires for the future may lead. In their stories, attempts to walk under the rainbow are akin to small exercises in hope(lessness). To chase the rainbow is to be forever in the middle of an impossible journey. This chase could be described as a disruptive journey to “somewhere free of the signs for the body” (Dianne Brand, 2001), since it requires the chaser to be willing to literally lose her body as she knows it, to open it up to new (sexual, gendered) possibilities other than arriving at the other side.

Similarly, the rainbow, as an unreachable arc presiding over ambiguous, hybrid and conflicting sites of identification and memory making, demands that literary critics, historians, film scholars and artists fully engage with the possibility of failing to produce the memory that the rainbow incites.

It is from this improbable, indeed impossible, location that I aim to develop a framework for claiming under-theorised memory sites of the Brown Atlantic beyond forms of spatially bounded memory. The rainbow, and the Brazilian saying linked to it, constitute the conceptual centre of this study, bringing forth an understanding of the past as an improbable threshold that cannot be crossed but only precariously pursued.

Welcome to the Exeter Language and Culture Blog

We are thrilled to inaugurate this new blog, hosted by the Department of Modern Languages at the University of Exeter. We will be posting here about issues relating to and arising from our activities in teaching, scholarship, research and the promotion of language learning.

Recent Comments