Author: Tom Jenkins (PhD Student) – Biosciences, Streatham Campus

I started my PhD study under the supervision of Dr Jamie Stevens at the University of Exeter in October 2014 on a NERC Great Western Four+ Doctoral Training Partnership (GW4+ DTP) studentship. This programme was appealing to me because it encouraged collaborations among academic and non-academic partners to achieve mutual research objectives in environmental science. Natural England, the UK government’s advisor for protecting the natural environment in England, is the official non-academic partner linked with my PhD. In our research group, the Molecular Ecology and Evolution Group (MEEG), we use a variety of molecular techniques to examine variations in the DNA of various aquatic and terrestrial species in an effort to answer questions about the population biology and ecology of these animals. Of particular interest to me is the application of such data to inform and address matters of marine conservation and management.

Marine connectivity

Connectivity is generally defined as the degree to which individuals/larvae/eggs are exchanged between populations, the study of which allows us to estimate dispersal distances and explore patterns of immigration between populations of a species. For some marine species, high connectivity can be extremely important for the persistence of isolated populations or for (re)colonising habitats that become available. One of the aims of marine conservation is therefore to establish Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) of adequate size and spacing to help maintain natural connectivity by reducing human disturbance in key or vulnerable areas.

My research

My PhD centres on assessing the connectivity of two bottom-dwelling marine invertebrates around UK and western European coasts, the pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa) and the European lobster (Homarus gammarus). To do this, I am using molecular markers to study patterns of population genetic structure across both species’ geographical ranges. These data allow us to detect genetic similarities or differences between populations, which we can use as a proxy for indirectly estimating the amount of connectivity between discrete populations (i.e. ↑ similarity = ↑connectivity – but evolutionary processes other than connectivity can also influence the genetic structure of populations which can complicate interpretations of the data!).

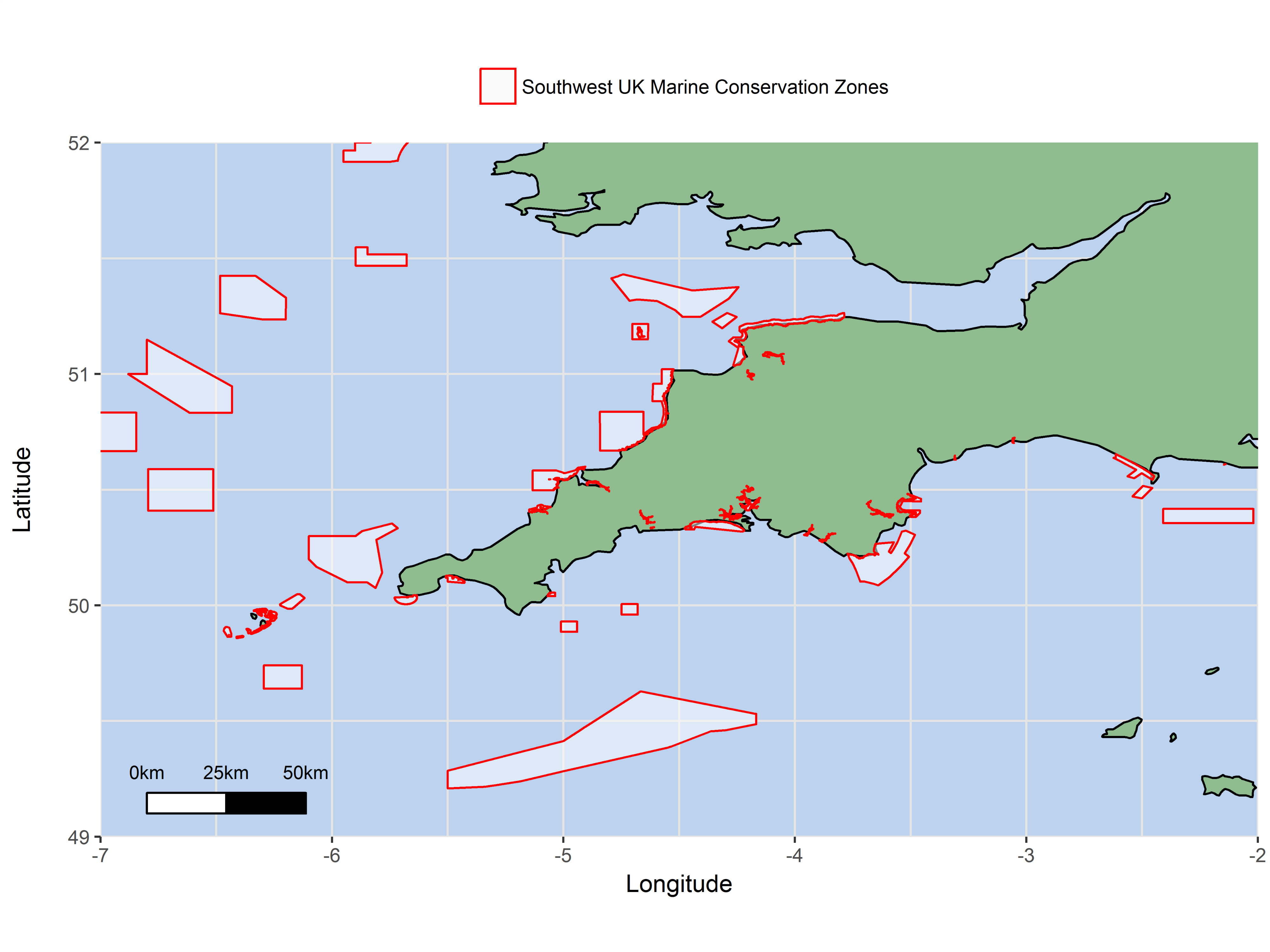

Pink sea fan

The pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa) is a cold-water soft coral that is protected in the coastal waters of England and Wales by the UK government, and it is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Because of its rarity across the UK, several Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs) have been specifically designated around southwest Britain with the protection of pink sea fan colonies in mind (e.g. The Manacles MCZ). Our published research found that at distances of >500 km, pink sea fan colonies are likely to follow a stepping-stone model of connectivity, such that colonies which are closer together are more connected than those further apart. In contrast, at distances <500 km, we found that populations were genetically quite similar, suggesting high connectivity between areas at this spatial scale. For the colonies sampled across southwest Britain, high connectivity was apparent which suggests that the network of MPAs in southwest England and Wales appears to be sufficient for maintaining connectivity in this species! We think that this could be useful evidence to support the existing MCZs designated around southwest England and Wales.

European lobster

The European lobster (Homarus gammarus) is a crustacean typically found hiding in crevices on rocky substrates at depths from the low tide mark to 50-150 metres. Their high market value means they are targeted by fishermen and therefore it is important that these fisheries are managed sustainably.

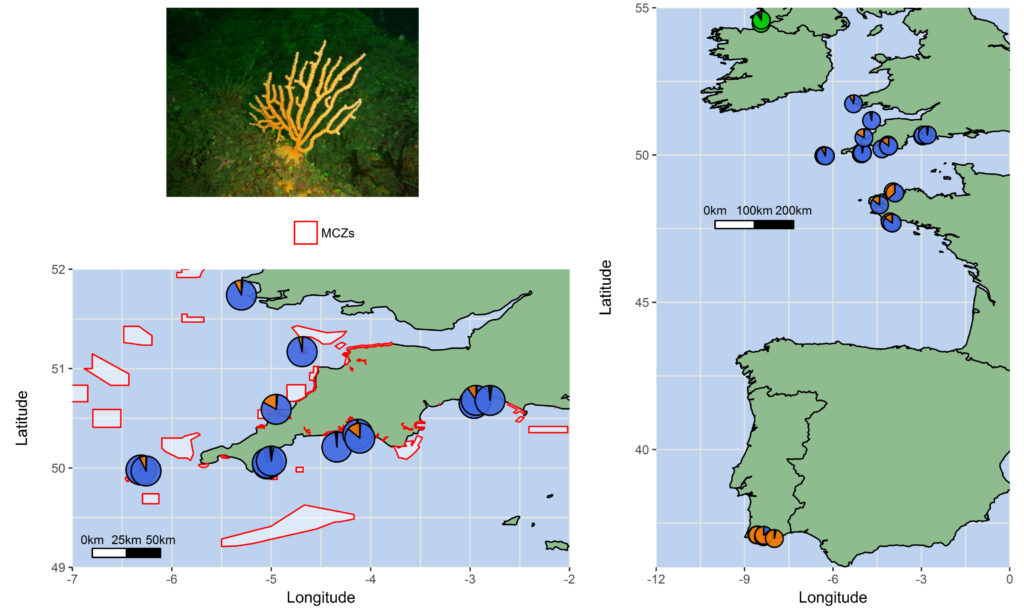

For this lobster study, I have been fortunate enough to collaborate with the National Lobster Hatchery (Padstow, Cornwall) and members of the public (e.g. local fishermen/shellfish merchants) which has massively helped me to collect tissue samples for genetic analysis across most of the range of European lobster (from the Mediterranean to the British Isles and Scandinavia).

At this stage, I have isolated variations in DNA sequences known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from across the genome – this panel of SNPs was recently published and will hopefully be a useful resource for future genetic studies of European lobster. My ongoing work is using this SNP panel to explore the population genetic structure of European lobster across our sampling sites. For me, it will be very interesting to find out what patterns of connectivity are present across these geographical areas and, moreover, the results may help the National Lobster Hatchery decide where they can release their Cornwall-bred juvenile lobsters without impacting the natural genetic make-up of the lobster population being restocked.

This blog accompanies a new paper in Marine Policy, read here.

#ExeterMarine is a interdisciplinary group of marine related researchers with capabilities across the scientific, medical, engineering, humanities and social science fields. If you are interested in working with our researchers or students, contact Michael Hanley or visit our website!