Author – Maisie Jeffreys, MSc Student – Molecular Ecology and Evolution group

Elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays) are more vulnerable to extinction than any other vertebrate group, meaning their protection is more important than ever. However, confusion remains surrounding the taxonomy of many species- making conservation difficult. Hence, more research needs to be done to answer taxonomic questions that still surround these endangered species.

Elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays) are more vulnerable to extinction than any other vertebrate group, meaning their protection is more important than ever. However, confusion remains surrounding the taxonomy of many species- making conservation difficult. Hence, more research needs to be done to answer taxonomic questions that still surround these endangered species.

Elasmobranchs are some of the most fascinating creatures of the underwater world. Currently, there are at least 1,118 extant species of sharks, skates, and rays found throughout all corners of the globe: from depths of up to 4,000m in the deep sea and the icy waters of the Arctic, to shallower habitats in estuaries and freshwater lakes. Indeed, this group of cartilaginous fish can be found in just about every aquatic ecosystem on the planet, where they play vital roles in maintaining ecosystem balance.

Unfortunately, elasmobranchs are a group at high risk of extinction; due to habitat destruction, overfishing, and being caught as bycatch, an estimated 25% of species are thought to be threatened worldwide. The impact of elasmobranch decline is poorly understood, but given their important roles in aquatic ecosystems, the consequences are likely to be far-reaching.

Of all the elasmobranchs, the batoids (skates and rays) are the most vulnerable, with around 20% now threatened with extinction. Despite this, effective conservation of batoid fish has been hindered by a lack of accurate scientific data; many species are now listed as ‘data deficient’ on the IUCN red list, making establishing accurate conservation methods difficult.

This lack of data can be partially attributed to the large degree of morphological and ecological similarities among living orders of skates and rays. These similarities cause high amounts of cryptic speciation (animals that look alike but are genetically distinct), which results in taxonomic confusion and unstable nomenclature.

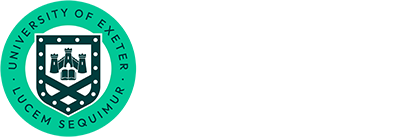

A classic example of cryptic speciation can be found in the Manta rays. Currently, there are two species of Manta ray; the larger species, Manta birostris, can grow up to 7 m in width, while the smaller, Manta alfredi, reaches 5.5 m. However, these were thought to represent just one species until 2009, due to their morphological similarities. This discovery has been vital in the conservation of mantas, particularly as it has allowed the clarification of the two species’ ranges. Since M. birostris is thought to migrate across open oceans, while M. alfredi tends to be resident and coastal, conservation efforts have now been targeted accordingly.

My Masters by Research focusses on resolving taxonomic questions that still surround several other species of endangered rays and skates, including the ‘common skate’ complex (Dipturus cf. flossada and Dipturus cf. intermedia), the Norwegian skate (Dipturus nidarosiensis), the longnose skate (Dipturus oxyrinchus), the thornback ray (Raja clavata) and the Madeiran skate (Raja maderensis). In order to answer these questions, I will be using restriction-site associated DNA sequencing (nextRAD) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing to build phylogenetic trees for analysis. This work could potentially lead to the discovery of new species of endangered skate and has important conservation implications for batoid fish.

This project, supervised by Dr Andrew Griffiths and Dr Jamie Stevens, forms just one part of a host of exciting work being done by the Molecular Ecology and Evolution group (MEEG) here at Exeter University. Several other marine projects are currently underway, including research into the population genetic variation of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), and genetic connectivity in tropical corals and temperate invertebrate systems.

#ExeterMarine is an interdisciplinary group of marine related researchers with capabilities across the scientific, medical, engineering, humanities and social science fields. If you are interested in working with our researchers or students, contact Michael Hanley or visit our website!