Hello all you cool catfish and kittens!

My name is Ben Williams and I am a member of the marine bioacoustics group led by Professor Steve Simpson in Exeter. I’ve recently finished my Masters by Research thesis and I’m now fortunate enough to be working at Centre de Recherches Insulaires et Observatoire de l’Environnement (CRIOBE) on the island of Moorea, French Polynesia. I primarily study tropical reef soundscapes, which operates around the concept that we can learn about coral reef ecosystems simply by listening to the life on these surprisingly noisy habitats. My colleague, Isla Hely, who I’m working with here in Moorea, recently shared a blog post on the events that led up to this expedition, navigating fieldwork prep in a global pandemic, and what we’re working on. In this blog post, I’ll share a few more details on my journey over the past 18 months that led up to where we are now!

Jumping back to September 2019, I had finished my undergraduate degree, an internship with the Exeter bioacoustics group in Indonesia and a second with PhD student Lauren Henly. I was just a few days away from starting my MRes when I got a call from Steve asking if I was interested in changing my plans and joining the team for two months at Lizard Island Research Station on the Great Barrier Reef, just three weeks before departing. Needless to say, I didn’t turn this down! During this fantastic opportunity, I was able to assist more senior group members in their research whilst working on the first chapter of my MRes. I learnt so much more about marine fieldwork and gathered some great data exploring the utility of consumer grade recorders to collect soundscape recordings. During this, I of course remember hearing about the events in Wuhan, thinking “Surely this will boil over soon?”, but our naivety to the world was set to change for the foreseeable future.

Once I had returned and commenced the write up of my first chapter, I began putting in grant applications for the second half of my MRes. At this point, Steve made plans for me to join Isla in Mauritius where I would be able to lead a project studying a unique network of artificial reefs whilst reciprocally helping Isla with her research. Our funding bids were successful and I was days away from booking tickets to arrive in late March. However, just like everyone else’s year, these plans were turned on their head by the pandemic. So, Isla returned and we spent the next few months waiting to see if these plans were going to be possible. Sadly, the Wakashio oil spill also occurred in July, which was devastating to many of the reefs around the island and the final nail in the coffin to this expedition.

Research students were one group of many who faced challenges as a result of the pandemic, with months of preparation, work or experiments thrown out the window. I found myself having to go back to the drawing board for my second chapter. I therefore opted to explore some data I had helped the group collect previously in Indonesia. This was recorded at one of the world’s largest reef restoration projects – myself and Ellie May wrote a couple of blog posts for Exeter Marine about this work. Here we wanted to determine whether we could find a difference between healthy and degraded reef soundscapes, and whether this could be used to indicate the progress of restored sites. The project lead, Tim Gordon, had explored some really interesting angles with this data so far, and I was left scratching my head as to how I could build on this. But, through perseverance a eureka moment came when I found we were able to combine computationally generated metrics from these recordings and some complex statistical analysis skills I had learnt during my undergraduate degree. This turned out to be some of my best work to date and I was delighted to have been able to make the best of a bad situation!

So, after two awesome fieldwork seasons, countless hours of programming in ‘R’, learning to use new pieces of software such as GraphPad, MATLAB and Audacity, I was able to put together my 27,000 word thesis and polish this off with my supervisors Steve Simpson and Lucille Chapuis.

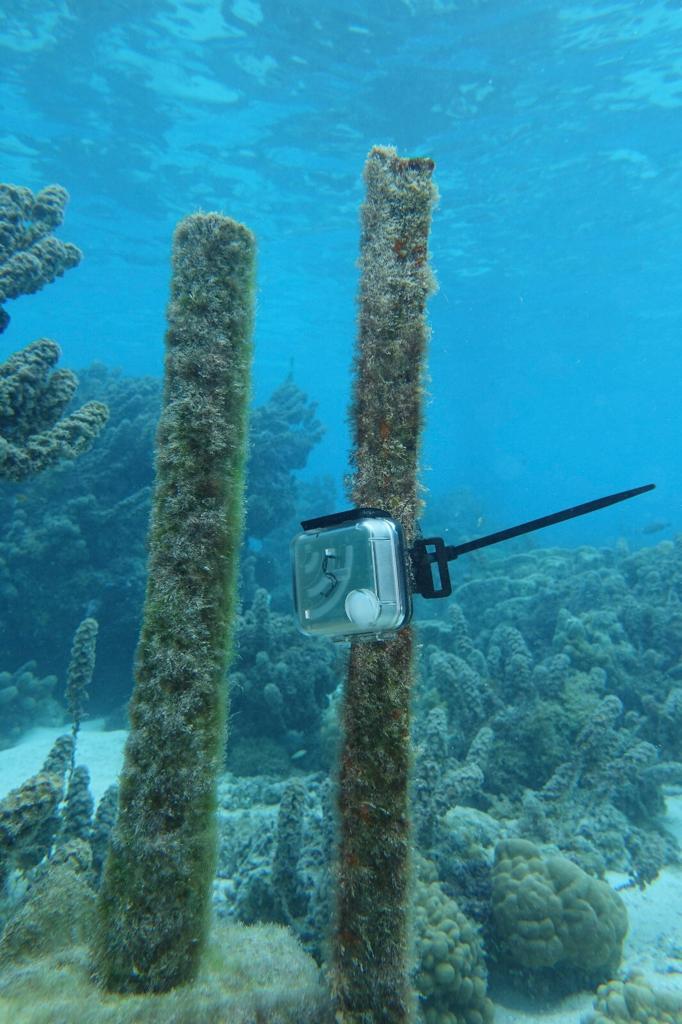

I was then immediately able to move on to work here in Moorea for the next three months, alongside Isla Hely, with the generous support of Exeter Marine, the Fisheries Society of the British Isles, and the Challenger Society for Marine Science. Here, I’m trialling some exciting new recording technology known as AudioMoths, which came about after setting up a collaboration with the developers who are helping us bring AudioMoths to the marine environment. These recorders have a lot of potential to provide an intelligent, open source, and cost effective alternative to our typically £2000+ hydrophones. I’m also studying the impacts of artificial light at night (ALAN) on reef fish as well as one or two other projects we’re keeping quiet for now! It has been brilliant to join long-term collaborators with Exeter, Suzanne Mills and Ricardo Beldade, who are leading the ALAN work here and have played a huge part in making our fieldwork happen. Myself and all involved are also very aware of how fortunate we have been to be able to commence this work, and remain very grateful to all the incredible people at the University of Exeter and CRIOBE who have made this possible!

Myself and Isla will be sharing more on our work in the coming weeks, for now you can follow me on twitter (@_ExeBen_) and Instagram (@bwilliams1995) where I’ve been posting updates on our work!

#ExeterMarine is an interdisciplinary group of marine related researchers with capabilities across the scientific, medical, engineering, humanities and social science fields. If you are interested in working with our researchers or students, please visit our website!