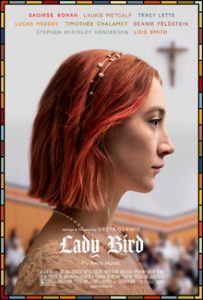

Who doesn’t love that scene in Lady Bird (Gerwig, 2017) when she throws herself out of the car to make a point to her obstinately loving mother about wanting to go to a college far away? There’s something in the mother-daughter relationship that powerfully encapsulates the frustration of not making oneself understood. Yet it’s all too rare to find a popular film that explores this frustration without demonizing that mother figure. This is because questions of voice and being heard are closely intertwined with the changing fortunes of feminism and postfeminism. Until lately, popular cinema has tended to align the daughter with a good, fun-loving postfeminism and the mother with a bad, prickly feminism (Rowe Karlyn, 2011). Think of witty Juno and the silent, absent mother who sends her cactuses. In Lady Bird, by contrast, our sympathies are divided between mother and daughter by comic self-consciousness. Lady Bird’s action is hilariously melodramatic, not tragic, and our horrified laughter perhaps puts us partly on the side of her exasperated mother.

When Waters and Munford (2014) wrote that ‘feminism is a ghost that popular culture cannot lay to rest’, they seemed to anticipate the recent, powerful return to feminism that films like the Italian Cosmonauta (Nicchiarelli, 2008) and the British Ginger and Rosa (Potter, 2012) call for. Both films are set in the early 1960s, the twilight years of the ‘feminine mystique’, when middle-class women often found themselves trapped in an idealized and passive domesticity. Their stories are told through the eyes of appalled daughters who come to a slow understanding of their mothers’ apparently pitiful subjugation (mothers played by postfeminist icons, Claudia Pandolfi and Christina Hendricks, their glamour re-cast in domestic drudgery). Moving from contempt for their mothers’ lack of power, the girls learn the hard lesson that allegiance with patriarchal power eventually silences them as daughters too. In a memorable scene in Cosmonauta, 16-year-old Luciana finds that her contribution to Communist Party debate is only accepted when re-worded by a male teen colleague and that sexual experimentation sees her, but not her male lovers, punished. Ginger, on the other hand, finds her loyalty to her father forces her to remain silent about his devastating affair with her best friend, Rosa, leaving her feeling that she might explode. ‘What is it that you can’t say?’, asks her older (feminist) friend, Bella.

In a context of social silencing, the films seek to ‘envoice’ the girls through creative use of soundtrack, while the metaphors of space rockets and nuclear explosions that illuminate the socio-historical backgrounds also hint at a latent ‘illegible rage’. In the postfeminist context Angela McRobbie (2009) has defined this destructive feeling as a form of sickness experienced by young women when they are silenced. What silences them, she argues, is the popular discourse that they have achieved equality, and can no longer interpret their gendered experience as a possible reason for discontent: ‘the new female subject is, despite her freedom, called upon to be silent, to withhold critique in order to count as a modern, sophisticated girl’ (p. 34). The directors of these two films use a moment just prior to second-wave feminist activism to reflect on the dangers of this silencing and to highlight the continued need for feminist intervention by making it the hope-filled future for the girl protagonists of these films. Here, as Munford and Waters suggest, ‘the redeployment of images from the past serves the radical agenda of the feminist present by mounting a new feminist call-to-arms’ (pp. 169-171). This cinema seeks to make the girl the sympathetic forerunner of second-wave feminism, rather than a fun-loving postfeminist frustrated by feminism’s humourless or absent embodiment in the mother . Since 2017 #Metoo has given vent to a social media explosion of rage, taking shape as a chorus of hitherto silenced female voices. As new forms of popular feminism emerge, how will cinema revisit themes of generational difference, feminism and voice? The more recent Lady Bird seems to represent a shift, in which the voices of mothers and daughters no longer re-present stages of feminism and postfeminism in conflict, but engage in much more nuanced and emotionally complex dialogues, informed, on both sides, by various shades of feminism itself.

Key Films

More Films

Further Reading

- Kathleen Rowe Karlyn, on Meangirlsin Unruly Girls, Unrepentant Mothers: Redefining Feminism on Screen (University of Texas Press, 2011), pp. 88-92

- Ros Gill, ‘Postfeminist media culture: Elements of a sensibility’, European Journal of Cultural Studies10:2 (May 2007), 147-166

- Suzanne Ferriss and Mallory Young, ‘Introduction: Chick Flicks and Chick Culture’, in Chick Flicks: Contemporary Women at the Movies(London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 1-26

- Sarah Gamble, ‘Postfeminism’, in The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Postfeminism (London: Routledge, 1998), 36-45

- Frances Gateward and Murray Pomerance, ‘Introduction’, in Sugar, Spice and Everything Nice: Cinemas of Girlhood (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press)

- Rosalind Gill, ‘Post-postfeminism?: new feminist visibilities in postfeminist times’, Feminist Media Studies(2016), 16:4, 610-630