By Joel Rodrigue (Vanderbilt University) and Yong Tan (Nanjing University of Finance and Economics)

For the typical Chinese exporter, foreign sales grew exponentially after China’s entry to the WTO. How was this so-called ‘economic miracle’ achieved in such a short span of time? Answering this question has been the focus of policymakers, government officials, and academic researchers across the globe.

Our recent paper adds to a rich literature studying the determinants of Chinese export growth.[1] In particular, we examine the impact that consumer loyalty has on the market strategies adopted by Chinese firms to successfully grow into high-value export markets. Even if they were aided by falling trade costs, convincing foreign consumers to purchase Chinese goods for the first time is no small feat. To clear this hurdle we argue that Chinese firms systematically chose to enter markets producing low quality products and setting low prices.

This doesn’t mean the stereotype that Chinese exports are broadly low price or low quality is accurate. Rather, as foreign consumers adopted new Chinese goods, producers adjusted production to produce higher quality, higher price, higher-value varieties. In this sense, the rapid Chinese export-driven economic growth has occurred alongside an observable rise in the nation’s firm-level climb up the value-chain.

Our approach builds on the static O-ring models of endogenous quality choice under monopolistic competition.[2] We extend this setting to consider the dynamic pricing and product quality decisions by bridging this framework with models of habit persistence and demand accumulation.[3] A key outcome from this marriage of ideas is that exporting firms will alter markups and product quality over time in order to grow sales rapidly during the initial years after entry and develop a large customer base.

The degree to which firms care about the future, however, depends on the firm’s long-run outlook in competitive export markets. Small, unproductive firms are more likely to produce low quality products and yield little discount initially because they don’t expect to serve the same consumers more than once. In contrast, the most efficient firms optimally aim to reach consumers by offering good value for their dollar: high quality products at a relatively low price.

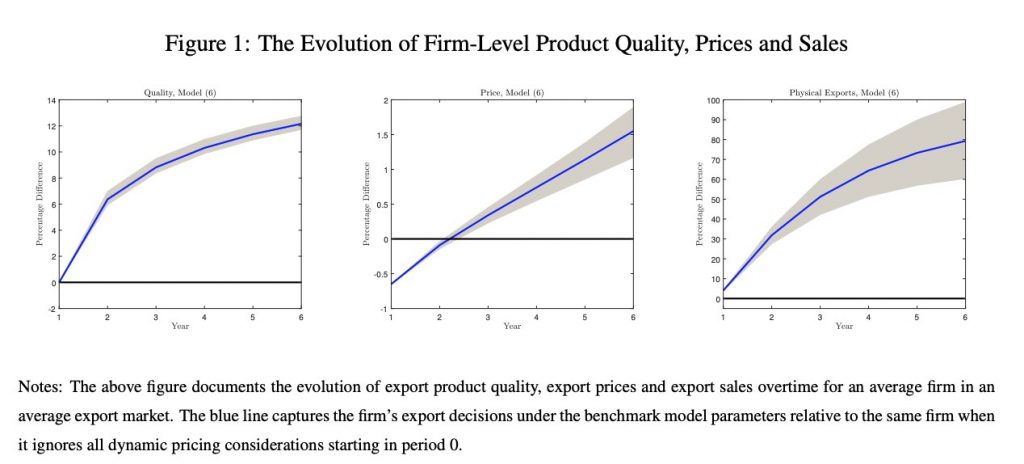

To fix ideas we focus on the production of electric kettles, a small electronic appliance, typical of much of China’s export growth. In Figure 1 we depict the evolution of export prices, product quality and export sales for a representative firm in a typical export market. New Chinese exporters, despite producing low quality varieties, sell these goods one percent cheaper than established firms selling the same quality of electric kettle. While this difference might sound small, it is worth at least 4 percent higher export sales in the firm’s first year – often the difference between breaking even or losing money when a firm enters new markets.

Over time the impacts are even larger. While the export sales of a typical kettle producer grew by nearly 80 percent between 2001 and 2006, Chinese producers systematically added new features to their products: stainless steel casings, rapid heating systems, larger capacity, etc. Adding these desirable product characteristics, however, is not free. Rather, we document that over a five-year period typical input costs rose by twelve percent to incorporate higher quality attributes.

Not surprisingly product quality upgrading is likewise found to drive a large part of Chinese export growth; observed product improvements account for at least 17 percent of the aggregate growth in kettle exports over the same time period. As Chinese firms further entrenched themselves in foreign export markets, their profits rose accordingly: markups increased by nearly 2 percent over the same time period as Chinese firms exported kettles at higher and higher profit margins.

The consequences for trade policy are manifold. In particular, price effects are likely to be muted in response to changes in trade policy. While tariff declines are found to directly reduce the price consumers pay, product quality upgrading has an opposing effect. Quality upgrading offsets price declines because high quality products are more expensive to produce, but also because it induces higher producer markups.

In contrast to the long march towards free and unfettered trade after WWII, recent tariff policy can broadly be characterized by unprecedented tariff increases in many countries. Nowhere is this more evident than US trade policy vis-à-vis China where tariffs have increased sharply, but – surprisingly – prices have remained remarkably stable despite the rise in trade costs.[4] Could this reflect changes in product characteristics and markups? That remains unclear. What is clear is that Chinese producers will react to tariff change on multiple fronts to maintain and grow their foothold in US export markets. Ignoring the multi-dimensional responses of producers can potentially misrepresent the nature and impact that tariff policy has on firm behavior.

References

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David Weinstein, (2018); “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare.’’ NBER Working Paper No. 25672.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo, Pinelopi Goldberg, Patrick Kennedy, and Amit Khandelwal, (2019); “The Return to Protectionism.” NBER Working Paper No. 25638.

Gilchrist, Simon, Raphael Schoenle, Jae. W. Sim, and Egon Zakrajsek, (2017); “Inflation Dynamics During the Financial Crisis.” American Economic Review, 107(3): 785-823.

Kugler, Maurice and Eric Verhoogen, (2012); “Prices, Plant Size, and Product Quality.” Review of Economic Studies, 79(1): 307-339.

Piveteau, Paul, (2018); “An Empirical Dynamic Model of Trade with Consumer Accumulation.” Working Paper, Columbia University.

Rodrigue, Joel and Yong Tan, (2019); “Price, Product Quality, and Exporter Dynamics: Evidence from China.” International Economic Review, forthcoming.

Endnotes

[1] Rodrigue and Tan (2019).

[2] See Kugler and Verhoogen (2012).

[3] In our model, habit persistence is based on Gilchrist et al (2017), while demand accumulation is based on Piveteau (2018).

[4] See Amiti et al (2018) and Fajgelbaum et al (2019).