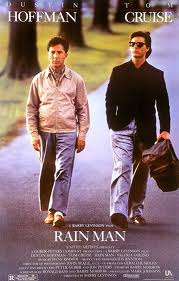

The next Screen Talks event will be on Monday 22nd April at Exeter Picturehouse. Dr Ginny Russell (Research Fellow at Egenis at the University of Exeter) will introduce Rain Man (Barry Levinson, 1988)

Join the event on Facebook and find out more here.

Booking Information: Book online, call the Box Office 0871 902 5730 or buy tickets on the door (half price for students on Mondays).

Dr Ginny Russell has written a guest blog post for us, outlining the film’s influence on the ways that autism is understood:

Rain Man was released in 1988 to overwhelmingly positive reviews. It is the story of yuppie Charlie Babbitt, played by Tom Cruise, and his estranged brother Raymond, played by Dustin Hoffman. Raymond is an autistic savant; his character was modelled on a person named Kim Peek, although not autistic, did have a developmental disability with similarities to autism. He was also a savant with an eidetic memory. Researching the movie, producers referred to the diagnostic criteria for autism to develop the characterisation.

Hoffman’s performance as Raymond is compelling and the character has enormous screen presence in the sense that you never know what he is going to do next. Rain Man won Best Film Oscar in 1988 as well as Best Actor for Hoffman. Despite his limitations, the audience is drawn to Babbet because in his case, normal rules do not apply. In this way, Babbet displays classic symptoms of autism: normal social rules are not easily understood or adhered to. Rain Man’s autistic-hero is a cinematic archetype with a long tradition: Zen, star of the Thai film Chocolate. Peter Seller’s idiot savant in Being There, and Tom Hank’s Forrest Gump are all heroes with limited intellectual and social capabilities who unwittingly conquer their worlds. It is the quality of innocence that draws us to these characters and to Raymond. Raymond is as naive as his brother is scheming and worldly, yet it is Raymond himself who eventually offers his brother the possibility of redemption: an emotional connection that transcends material gain.

For the autism community today, Rain Man had two important consequences. First it raised awareness of the condition, and in its wake has come a flood of popular autistic autobiographies: Temple Grandin, Daniel Tammet and Donna Williams notable amongst them. Autism’s increasingly high profile is most certainly partially responsible for the spectacular rising prevalence of the condition since Rain Man’s release. Such high profile media coverage has led to far greater recognition and application of the diagnostic label. The question of whether the rising prevalence of autism is entirely an artefact of changing diagnostic practice or whether there really are more children with autism today is the subject of my own research.

The second unintended effect of Rain Man was to inadvertently encourage a stereotype that autism equals special abilities. In fact, such savant skills occur rarely in autistic individuals, in about 1-10% of the population with autism according to Darold Treffert, the primary researcher in this field. Savant skills are known as islets of ability and a particular skill, maybe rote memory, artistic ability, or musical talent, is highly developed compared to other skills. Oliver Sacks has written beautifully about his experiences of such cases in his book An Anthropologist on Mars. The problem with the public notion of the autistic savant is it promotes an unhelpful stereotype of what is often a profoundly disabling condition. Most children with autism are profoundly affected, have no special talent, struggle with everyday tasks, and in many cases do not develop speech at all.

Rain Man is often cited by members of the emerging Neurodiversity movement who argue that autism should not be viewed as a sickness but an alternative and valid way of being. Autistic self-advocates frequently refer to Raymond Babbet and other autistic heroes in literature and documentary when they describe their own experience of autism. The philosopher Ian Hacking has suggested that such portrayals themselves shape and feedback into how the disorder is experienced and understood. In this way Rain Man provides a neat illustration of a representation of sickness on screen that has itself influenced understandings of diagnostic criteria as well as vice versa .

Dr Ginny Russell has written extensively about autism and how it is understood and diagnosed. Read more about Ginny’s research here.