Our next Screen Talks will be on Monday 16th December, 6.30pm at Exeter Picturehouse. Dr Will Higbee, an expert in French cinema in the Dept of Modern Languages at the University of Exeter, will introduce Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013). Will has written a guest blog post for us on the film:

As some of you will know, the Screen Talks partnership between Exeter University and the Exeter Picturehouse is organized around a series of themes. Our next film, Blue is the Warmest Colour (French title: La Histoire d’Adèle, chapitres 1 & 2) comes under the heading of ‘Hidden Classics of European Cinema’. The film was released in France earlier this year: a little soon then to objectively be declaring this a ‘classic’, even if it was awarded the prestigious Palme d’Or at the 2013 Cannes Festival. Similarly, given the amount of press coverage generated by the various ‘controversies’ associated with the film (of which more later), as well as more than 700 000 spectators in France to date, it would be hard for us to describe this film as ‘hidden’ in terms of being unknown or waiting to be discovered. Nevertheless, I’m delighted to have been asked to introduce Blue is… as part of the Exeter Screen Talks series; firstly because Kechiche’s films have been an important part of my teaching and research for a number of years now but also because I’m intrigued to find out what Exeter audiences will make of this latest offering from one of France’s most important contemporary directors, as he extends the range and focus of his work.

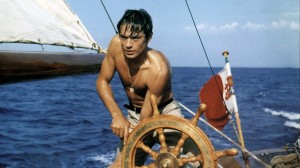

Abdellatif Kechiche was born in Tunisia and arrived in France at the age of six. He grew up on a working-class estate on the outskirts of Nice, not far from the city’s famous Victorine studios. During his youth, he indulged a passion for cinema through regular trips to the Nice cinémathèque, where he first discovered many of the great French actors – Michel Simon, Jules Berry, Harry Baur, Arletty – and later European directors such as De Sica, Pasoloini, Pialat and Sautet. After studying acting at the Conservatoire de Nice, he embarked on a career in the theatre that led to a limited number of film roles. The most notable of these saw him star as an attractive, streetwise Algerian immigrant finding his way in Paris in Le Thé à la menthe (Bahloul, 1984). The film was significant not only because it gave the young Kechiche his first major screen role but also because it was the first of a cluster of films released in France during the mid-1980s that focused on the experiences of the North African immigrant community and their French born descendants in France that became known as ‘Beur cinema’. Though the film was generally well received, Kechiche was unable to build on the initial success of Le Thé à la menthe. Reacting against what he saw as the lack of meaningful roles for French actors of North African origin in French film and TV, beyond stereotypical portrayals as immigrants, delinquents or criminals, Kechiche began to develop his own screenplays in the 1990s. Though encountering the usual problems facing first time filmmakers in attracting funding, in the space of a decade, through a series of four films starting with La Faute à Voltaire (2001), to L’Esquive (2005), La Graine et le mulet (2007) and Vénus noire (2010), which garnered birth critical and commercial success Kechiche moved from a relative unknown theatre and screen actor with aspirations to direct, to one of the most critically acclaimed filmmakers working in France today.

Kechiche’s standing in contemporary French cinema, made his fifth feature Blue is… one of the most eagerly anticipated films in official competition at Cannes in 2013. This sense of anticipation was heightened by the film’s subject matter: a coming of age narrative, inspired by a cult graphic novel by French artist Julie Morah, about a young woman exploring her sexuality, which includes extended and explicit scenes of lesbian sex.

Despite the film’s potentially controversial subject matter, and a demanding running length of three hours, Blue is… received rapturous attention from festival critics and audiences at Cannes and was awarded the Palme d’Or from a jury headed by Stephen Spielberg (the award was given collectively to Kechiche, and the lead actors Exarchopoulos and Seydoux). Respected scholar and critic Ruby B. Rich – widely credited for coining the term ‘New Queer Cinema’ to describe an emerging wave of independent films in the early 1990s focusing on gay, lesbian and transgender protagonists – claimed enthusiastically that Blue is… : ‘carries the female coming of age film into historic new territory.’

Blue is… focuses on the intense relationship between Adèle (played with extraordinary, instinctive force and intelligence by the, until then, little-known Adèle Exarchopoulos) a 17 year-old who is about to leave school and Emma, a confident art student and aspiring painter (played by one of the rising female stars of French cinema, Léa Seydoux). The film follows the development of their relationship and its continuing affect on Adèle’s life even years after the breakup as she builds a career for herself as a primary schoolteacher. As the film’s original French title suggests, Blue is… charts two defining periods in the life of the young Adèle, both of which are framed around her intense and transformative relationship with Emma. It is about her discovering and exploring her sexuality, to be sure, but it is also about her coming to terms with the possibilities and joy as well as limitations and disappointments that life offers her. These experiences are considered not only through her relationship with Emma but also in terms of her intellectual and professional development, as well as through the lens of class, due to her position as the child of working-class parents from a suburb of Lille (North East France) who becomes involved with the more self-assured Emma, the daughter of middle-class parents. (The differences between the two women’s backgrounds are reflected in the film through two very different meals in which Adèle and Emma bring their partner home to meet the respective parents).

Despite the much broader scope of the film, much of the critical discussion of this film has centred on the extended and explicit lesbian sex scenes (one lasting about ten minutes) that appear in the film. Clearly these scenes are an integral part of the film’s narrative as a means of expressing the transformative passion that Adèle’s relationship with Emma sparks in her. However, they form a clear minority of screen time in a film running for very nearly three hours. Arguably, the most memorable scenes in the film are actually those that occur outside of Emma’s candle-lit bedroom – such as the furious verbal and physical attack on Adèle by her classmates as the quiz her about her relationship with Emma, or the visceral intensity of the break-up scene between Emma and Adèle. Much of this intensity is achieved by Kechiche’s consistent, and at times almost overwhelming, use of the extreme close-up on his central actors. Interestingly, too, Kechiche employs the close-up (typically employed to emphasize the desirability of the star) to expose the flaws, insecurities and vulnerability of Adèle as well as her beauty.

In many ways, the film’s queer narrative and focus on white, French female protagonists, represented a departure of sorts for the Kechiche. His first three films had focused in different ways on the North African immigrant community in France, while his fourth (less well-received) feature, Vénus noire, recounted events from the final five years in the life of Sara Baartman, a Khoekhoe tribeswomen from the Cape Colony, who was transported as a servant from South Africa to Europe in 1810 and exhibited as the original “Venus Hottentot,” an object of curiosity, fear and prohibited (sexual) desire, first sold to a bourgeois consumer culture of the exotic in the freak shows in London and then to the libertine salons of nineteenth-century Paris. In truth, the move in Blue is… away from narratives with a focus on immigrant communities, questions of immigration and integration (as well as in the case of Vénus noire, a focus on European fascination with race and the body that would underpin the ideology driving European colonial expansion in the 18th and 19th century), shouldn’t matter. As Kechiche himself intimated in various interviews, his films should be judged primarily by his artistic sensibilities and worldview as a filmmaker rather than ghettoized by his ethnic origins. However, the fact that he is a high-profile French director who originates from one of France’s largest and most visible post-colonial minorities means that, whether we like it or not, there is a burden of representation related to his films – and that the question of the place accorded to immigrant minorities in his films will receive greater scrutiny than in the work of other French filmmakers. What is also noticeable is that Kechiche is one of the very few directors of North African origin working in France today who has been able or made a conscious decision to move away from making films that focus specifically on North African immigrant protagonists or themes of immigration and integration.

And yet, for all this talk of breaking new ground, on closer inspection Blue is… actually demonstrates considerable continuity with Kechiche’s earlier films. Certainly the predominance of blue (from Emma’s hair an denim, to the walls of Adèle’s bedroom, the postbox outside of the family home and the vibrant sea that surrounds Adèle towards the end of the film) reflects a deliberately stylized use of colour not seen in Kechiche’s previous work. However, other elements of form and style (most notably the use of extreme-close ups) have been a noticeable authorial signature in Kechiche’s work since his second feature film, L’Esquive. Similarly, the emphasis on food and mealtimes as moments of celebration, performance but also social critique, reflecting a preoccupation with the cultural politics of class and taste, as well as references to canonical works of French literature (especially Marivaux) have appeared in all of Kechiche’s previous films. Nor is the focus on female subjectivity necessarily anything new for this director. La Graine et le mulet was praised by French critics upon its release in 2007 for foregrounding of a range of strong and independent female protagonists of North African origin: protagonists that were conspicuous by their absence in most Maghrebi-French and North African émigré filmmaking of the 1980s and 1990s. Finally, the focus on the social milieu of the school and the world of the adolescent found in Blue is… had also been explored previously by Kechiche in L’Esquive.

The near universal acclaim that Blue is the Warmest Colour received at the Cannes festival was not, however, replicated upon the film’s general release in France. Kechiche became embroiled in a very public row following a series of articles written by Le Monde’s culture editor, Aureliano Tonet in which Tonet suggested that certain members of the crew working on the shoot found the director’s intense approach to his art and unconventional working practices as bordering on ‘moral harassment’. More damaging, though, was the fallout between the director and his two lead actors, with Seydoux and Excharchopolus commented in interviews that the shoot was a “horrible” experience, painting Kechiche as an overbearing, aggressive and unsympathetic director, with both actors openly declaring that she would never work with the director again. Excharchopolus has since softened her stance, while tensions still run high between Seydoux and Kechiche. In a recent and lengthy opinion piece published for a respected news website in France, which some commenters viewed as verging on paranoia, Kechiche suggested that Seydoux’s behavior was part of a wider campaign against him by certain influential members of the French film industry, even alluding to the possibility of legal action for what he saw as Seydoux’s attempt along with others to sabotage the film at the box-office.

Alongside this protracted and increasingly bitter public spat between Kechiche and Seydoux, more recent reviews of Blue is… have questioned the director’s portrayal of the sex scenes as being shot from a male perspective that somehow evokes a heterosexual fantasy of gay love. In her review for Sight and Sound that coincided with the film’s UK release, Sophie Mayer argued that: “As with many fantasies of lesbianism, the film centres on the erotic success and affective failures of relations between women”. For her part, Julie Maroh (author of the graphic novel that inspired the film) blogged that while she and Kechiche shared a desire to explore ‘how a romantic encounter happens, how a love stories builds and collapses and what remains of that love’, she found the sex scenes unconvincing (wondering if any lesbians were ever present on set to advise the actors). She described her experience of viewing these scenes from Blue is… in the following way:

“The heteronormative laughed because they don’t understand it and find the scene ridiculous. The gay and queer people laughed because they [the straight director and actors] don’t understand it…And among the only people we didn’t hear giggling were the potential guys too busy feasting their eyes on an incarnation of their fantasies on screen.”

Though not responding directly to Maroh’s remarks, Kechiche had the following to say in an interview with Sight and Sound to a question from Jonathan Romney about the director being out of his depth depicting a lesbian relationship:

“…it’s like saying a man has no right to depict a woman or a woman’s emotion because his view would be flawed…It’s really dangerous to enclose homosexuality in a category of special, distinct beings – that’s where racism starts…”

Whatever position you wish to take on these more controversial elements of the film’s production and reception – and this is something hopefully that we can debate in the post-film discussion at the Picturehouse bar after the film’s screening on the 16th – there is no denying that Kechiche has produced a film of considerable power and intensity, matched by the performance of Excharchopoulous as Adèle that speaks to Kechiche’s desire to create ‘a cinema of truth rather than a cinema of reality.’

Dr Will Higbee researches and publishes widely in French and diasporic cinemas, his book