Home » Articles posted by Site Admin

Author Archives: Site Admin

Remote Work in Tax Administrations Survey

By Ioannis Lentas, Nikolaos Moustakidis and Bettina Derpanopoulou

Human Resources Directorate

Independent Authority for Public Revenue, Hellenic Republic

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on health and the economy across the globe. Governments have taken measures to control the spread of the virus and the consequences arising from this. These measures, include, for example, restriction of movement, social distancing, closed schools, and mandatory working from home. Though the production chain has been severely affected, governments have responded quickly by putting plans in place for ‘Remote Working’ (or ‘teleworking’). This blog discusses the results of a survey conducted by the Independent Authority for Public Revenue (IARP) of Greece via the Intra-European Organisation of Tax Administrations (IOTA) network. The objective of the survey was to better understand the challenges around ‘Remote Working’ in tax administrations and, importantly, identify the extent to which this mode of working can be sustained in the future. The survey was carried out during the summer of 2020 (through June-August) and it involved HR department managers from twenty two Tax Administrations [1]. The survey consisted of 13 closed questions.

With the risk of oversimplification the survey shows that respondents thought that:

- tax administrations have reacted quickly to introduce remote working,

- remote working, if managed well, can help in enhancing productivity but the impact on well-being needs to be understood and considered, and

- remote working cannot be applied horizontally across the organisations.

Figure 1: map of participating (in blue) countries

Main Findings

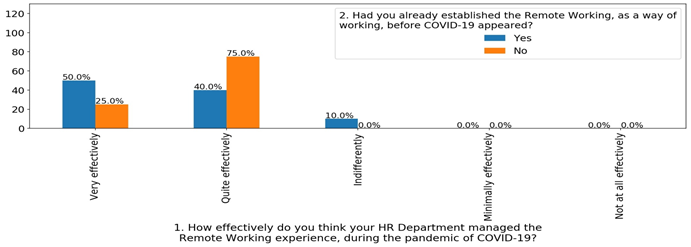

The majority of respondents (>95%) stated that their HR Department was effective in managing the remote working scheme during the COVID-19 pandemic, in spite of the fact that the majority (54.5%) had not previously established the practice before the start of the pandemic, in spite of the fact that the majority (54.5%) had not previously established the practice before the start of the pandemic.

Figure 2: Managing remote working

In addition, one third of the participants said that the organisation do not possess the technological equipment to effectively work away from their offices.

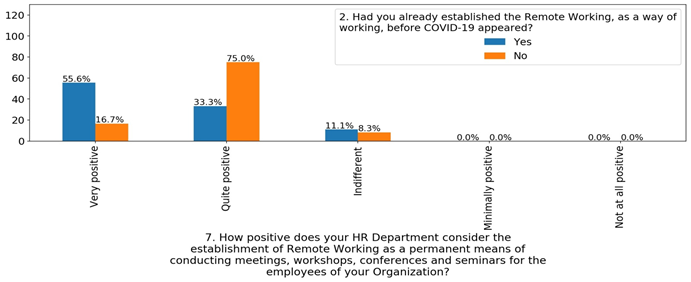

Interestingly, respondents (>90%) view the potential of remote working to conduct online meet-ups and seminars add real value to the organization.

The survey identified that respondents held different views on the frequency of ‘Remote Working’ and the needs associated with this, with most respondents preferring remote working for a specific number of days each week.

Remote working, however, is widely thought (80%) of being impossible to apply in a horizontal manner across all employee jobs and some differentiation would have to be made according to the tasks undertaken by the employees.

More specifically, the best fit for a remote working scheme was (in descending order): headquarter (70.6% selection rate), managerial, audit and lastly taxpayer service jobs (a mere 11.8% selection rate).

With regard to measures taken to help staff face the COVID-19 pandemic, tax authorities have responded quickly and provided information on contraction and spreading prevention measures. To a much limited extent, some organisations provided special care to vulnerable groups (45%) and 40% provided antiseptics.

A slim majority of respondents were also found to have conducted a survey to inquire staff members about their well-being (54.5%).

It was also reported by the vast majority of respondents (>90%) that their department (HR) was actively involved in the decision making process during the COVID-19 crisis.

Overall, a strong majority of over 85% of respondents appeared to be satisfied with the manner in which the crisis was handled by their organizations.

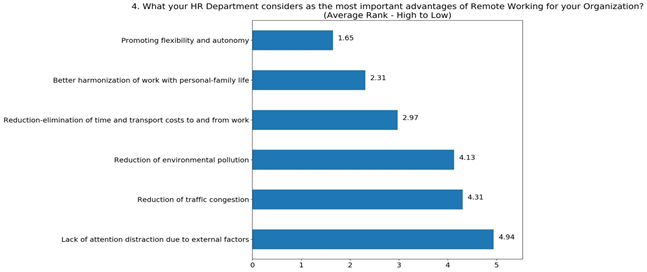

The top three recognised benefits of remote working comprise the flexibility and autonomy it offers, the improvement in professional-personal life balance and the elimination of transportation time and cost.

Figure 3: Advantages of remote working

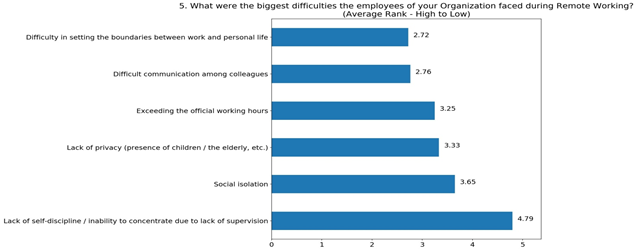

On the flip side, the three most important difficulties in applying remote working were identified to be issues of setting boundaries between work and personal time, difficulty in communication among colleagues, and exceeding the official work hours.

Figure 4: Difficulties of remote working

Effect of established Remote Working implementation

We now explore how respondents with and without previously established implementation of remote working schemes answered the questionnaire in order to identify how this prior experience affects their responses.

Previous experience in remote working appears to correlate with more positive assessments of the COVID-19 response to implement remote working.

Figure 5: Overall effectiveness assessment vs. established remote working implementation

Established remote working schemes also correlate to a more positive view of remote working as a permanent means of conducting meeting activities.

Figure 6: Remote working as a permanent means of meeting vs. established remote working implementation

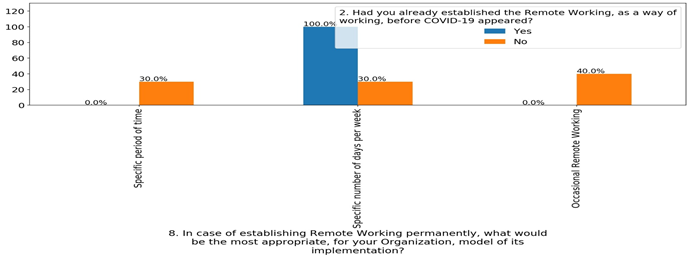

All respondents with established remote working agreed that a specific number of days per week is the more appropriate setup while those without were evenly split among the three options.

Figure 7: Remote working scheme selection vs. established remote working implementation

Those experienced with established remote working programs consider to a much higher degree (37.5% vs 8.3%) that remote working can be applicable to all jobs.

Another difference is the level of involvement that HR departments had in operational decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizations with established remote working were far more involved in the process (almost 90% reported ‘Fully’ participating) than those without (41.7% respectively).

Respondent Similarity – Clustering

Using the replies provided by the participating countries in the survey we can see how similar they are in their views and implementation on remote working and their response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Based on a similarity and clustering analysis three distinct clusters emerge:

Cluster No.1 comprising Belgium, Germany, Estonia, United Kingdom, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Finland features excellent overall response satisfaction, previous experience with remote working, high HR involvement in decision making, significant means to apply remote working, and highly positive attitude towards remote working for use in meetings.

Cluster No.2 comprising Bulgaria, Latvia, Belarus, Moldova and Romania features the second best rates (after cluster No.1) in overall response satisfaction and in positive attitude towards remote working for use in meetings.

Cluster No.3 comprising Armenia, Greece, Spain, Malta, Norway, Russia and the Czech Republic features the second best rates (after cluster No.1) in previous experience in remote working, level of HR involvement in decision making and in means to apply remote working.

Conclusion

The survey showed that remote working, even in the occasions that was introduced for the first time, functioned quite effectively. It also showed that there are productivity gains from remote working but under the condition that it is designed correctly.

Therefore, it is of high importance to understand its challenges and take them seriously into consideration so that it can become more sustainable for the future, more efficient in terms of productivity and more appropriate for the well being of the employees.

[1] The countries which participated into the survey are: Armenia, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Moldavia, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, United Kingdom.

COVID-19 and AFRICA: The World Should Take Bold Actions

Christos Kotsogiannis

Professor of Economics, University of Exeter, and Director of Tax Administration Research Centre (TARC)

Michael Masiya

Researcher at The African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF)

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the health and social fabric of society and the economy of countries across the globe. Nearly all countries to date have reported COVID-19 infected cases, but they have followed different trajectories as their exposure to the virus, their response and level of preparedness have differed. Europe and the US have been under a COVID-19 siege, while confirmed cases in Africa are lower but rising, albeit at a slower pace.

As of 21st May 2020, all 54 African countries had reported a collective total of 95,482 cases of COVID-19, with South Africa (18,003 confirmed cases) being top of the list closely followed by Egypt (14,229), then Algeria (7,542). The pandemic is affecting life significantly everywhere, but in Africa, the impact can be more long-lasting and devastating. Africa’s health infrastructure is the least developed in the world. As of April 2020, Central African Republic, for instance, with population of around 5 million, had just three ventilators. Sierra Leone, with a population of 7.5 million and Burkina Faso with a population of 19 million, each had less than twenty. Infant and maternal mortality are significantly high too, signifying the underlying challenges and the pressure on the health system.

African countries are predominantly agriculture-based economies, where populations engaged in agricultural activities live hand-to-mouth, with limited access to sustainable income. Estimates show that Africa has the highest rate of informality in the world, at 72 percent of non-agricultural employment, and that 94 percent of workers with no education are informally employed. Walking long distances to access basic amenities like water, firewood, and food makes lockdowns impractical in rural Africa (Madagascar, Malawi, Ethiopia and Kenya for example). In a March 2020 campaign to boost access to water in developing countries, the World Vision estimated that women and children in rural Africa walk an average of 6 Kilometers just to access safe water! A prolonged pandemic will also affect crops and therefore food prices. For instance, in Malawi, one of the top three most impoverished countries in the world, food contributes slightly over 45 percent towards headline inflation. Under these circumstances, informal sector workers may hardly appreciate the importance of social distancing rules and global impact of COVID-19.

Revenue mobilization has been an urgent issue over the years, but now with the pandemic it becomes more even more challenging, as governments announce relief measures to ease the impact of the pandemic. Kenya, for example, reduces the standard VAT rate from 16 percent to 14 percent, Malawi offers a 6 month tax amnesty and South Africa provides a tax subsidy of up to R500 per month ($26,60) for the next four months (from April 2020) for those private-sector employees earning below R6 500 ($346).

Whatever measures a country takes, inevitably there will be a loss in production and much-needed revenues. The Africa Purse (2020), for example, estimates that COVID-19 will cost Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) between $37 billion and $79 billion in output losses for 2020. This is due to a combination of effects, ranging from trade and value chain disruption, to disruptions caused by containment measures. Further estimates suggest economic forecast for SSA will fall sharply from 2.4% in 2019 to -2.1 to -5.1% in 2020 due to the impact of COVID-19. This will have a significant impact on the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development which is the most comprehensive blueprint to date for eliminating extreme poverty, reducing inequality, and protecting the world at large. The anticipated recession of Africa economy due to COVID-19 will surely delay meeting the 2030 Agenda targets.

Lack of containment of COVID-19 (and the uncertainty surrounding the behaviour of the virus itself) could also cause displacement of people and increase the migration flows from Africa into Europe. And it will surely worsen poverty and inequality, due to large numbers of fatalities in poorer communities.

World Bank data shows that debt service in 2018 was approximately 2.1% of regional GDP. To service this debt and simultaneously provide for a policy stimulus by redirecting expenditure on health will be nearly impossible. The challenge has prompted discussions in international institutions (World Bank and the IMF) for a bilateral debt standstill, to soften the impact of COVID-19. The G20 too have recognized that coordinated effort is required to support Africa in dealing with the economic and social consequences of COVID-19.

While these are welcome discussions, care of course must be exercised in making sure that the funds are directed for their intended purpose. In some countries, where elections are coming up, diverting funds towards electoral campaigns might be very tempting According to a 2015 report released by the African Union’s (AU) high-level panel on illicit financial flows and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), Africa is estimated to be losing at least US$50 billion annually to illicit financial flows, including fraud, tax avoidance, offshore investments and siphoning of billions of dollars meant for the poor. At the time when the whole world is facing a crisis and the G20 trade some of their stimulus off to Africa, the best way to give back is to enforce the utmost levels of good governance in handling the relief or funds. Beneficiaries must ensure that the stimulus is solely directed towards mitigating the impact of COVID-19.

Recently, 18 leaders signed a letter (see ‘Only victory in Africa can end the pandemic everywhere’, FT 14/04/2020) arguing for a stimulus package of at least $100bn so African countries have enough fiscal space for health expenditure (including, procurement of medical supplies and equipment, building diagnostic capacity and training and improving the health screening of people) but also for mitigating the economic and social consequences of the pandemic. The arguments are well justified. This is not an economic crisis, but a crisis caused by a global pandemic. The world should collectively take bold actions.

Recent Comments