Home » COVID-19

Category Archives: COVID-19

Remote Work in Tax Administrations Survey

By Ioannis Lentas, Nikolaos Moustakidis and Bettina Derpanopoulou

Human Resources Directorate

Independent Authority for Public Revenue, Hellenic Republic

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on health and the economy across the globe. Governments have taken measures to control the spread of the virus and the consequences arising from this. These measures, include, for example, restriction of movement, social distancing, closed schools, and mandatory working from home. Though the production chain has been severely affected, governments have responded quickly by putting plans in place for ‘Remote Working’ (or ‘teleworking’). This blog discusses the results of a survey conducted by the Independent Authority for Public Revenue (IARP) of Greece via the Intra-European Organisation of Tax Administrations (IOTA) network. The objective of the survey was to better understand the challenges around ‘Remote Working’ in tax administrations and, importantly, identify the extent to which this mode of working can be sustained in the future. The survey was carried out during the summer of 2020 (through June-August) and it involved HR department managers from twenty two Tax Administrations [1]. The survey consisted of 13 closed questions.

With the risk of oversimplification the survey shows that respondents thought that:

- tax administrations have reacted quickly to introduce remote working,

- remote working, if managed well, can help in enhancing productivity but the impact on well-being needs to be understood and considered, and

- remote working cannot be applied horizontally across the organisations.

Figure 1: map of participating (in blue) countries

Main Findings

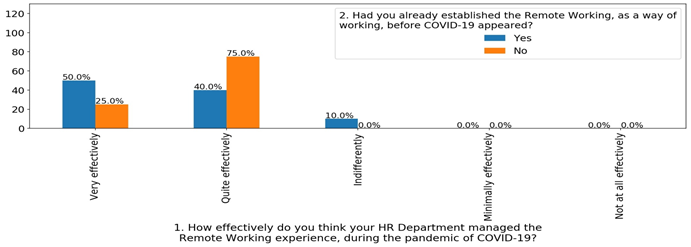

The majority of respondents (>95%) stated that their HR Department was effective in managing the remote working scheme during the COVID-19 pandemic, in spite of the fact that the majority (54.5%) had not previously established the practice before the start of the pandemic, in spite of the fact that the majority (54.5%) had not previously established the practice before the start of the pandemic.

Figure 2: Managing remote working

In addition, one third of the participants said that the organisation do not possess the technological equipment to effectively work away from their offices.

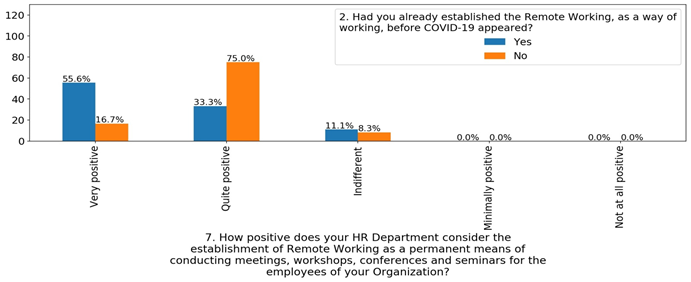

Interestingly, respondents (>90%) view the potential of remote working to conduct online meet-ups and seminars add real value to the organization.

The survey identified that respondents held different views on the frequency of ‘Remote Working’ and the needs associated with this, with most respondents preferring remote working for a specific number of days each week.

Remote working, however, is widely thought (80%) of being impossible to apply in a horizontal manner across all employee jobs and some differentiation would have to be made according to the tasks undertaken by the employees.

More specifically, the best fit for a remote working scheme was (in descending order): headquarter (70.6% selection rate), managerial, audit and lastly taxpayer service jobs (a mere 11.8% selection rate).

With regard to measures taken to help staff face the COVID-19 pandemic, tax authorities have responded quickly and provided information on contraction and spreading prevention measures. To a much limited extent, some organisations provided special care to vulnerable groups (45%) and 40% provided antiseptics.

A slim majority of respondents were also found to have conducted a survey to inquire staff members about their well-being (54.5%).

It was also reported by the vast majority of respondents (>90%) that their department (HR) was actively involved in the decision making process during the COVID-19 crisis.

Overall, a strong majority of over 85% of respondents appeared to be satisfied with the manner in which the crisis was handled by their organizations.

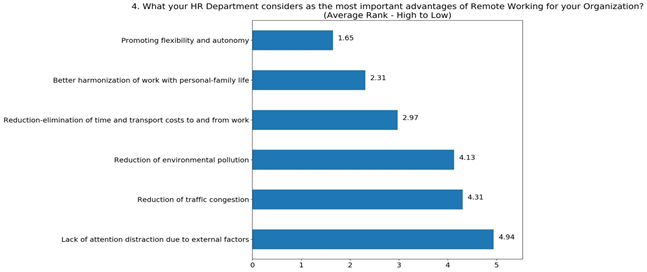

The top three recognised benefits of remote working comprise the flexibility and autonomy it offers, the improvement in professional-personal life balance and the elimination of transportation time and cost.

Figure 3: Advantages of remote working

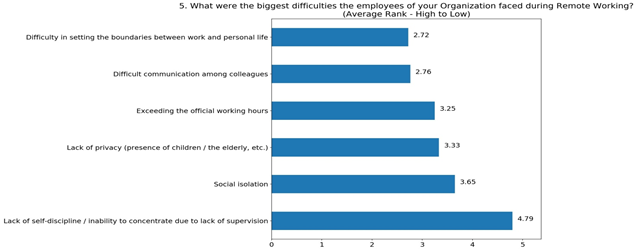

On the flip side, the three most important difficulties in applying remote working were identified to be issues of setting boundaries between work and personal time, difficulty in communication among colleagues, and exceeding the official work hours.

Figure 4: Difficulties of remote working

Effect of established Remote Working implementation

We now explore how respondents with and without previously established implementation of remote working schemes answered the questionnaire in order to identify how this prior experience affects their responses.

Previous experience in remote working appears to correlate with more positive assessments of the COVID-19 response to implement remote working.

Figure 5: Overall effectiveness assessment vs. established remote working implementation

Established remote working schemes also correlate to a more positive view of remote working as a permanent means of conducting meeting activities.

Figure 6: Remote working as a permanent means of meeting vs. established remote working implementation

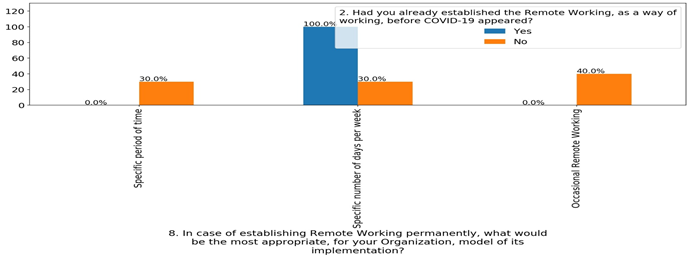

All respondents with established remote working agreed that a specific number of days per week is the more appropriate setup while those without were evenly split among the three options.

Figure 7: Remote working scheme selection vs. established remote working implementation

Those experienced with established remote working programs consider to a much higher degree (37.5% vs 8.3%) that remote working can be applicable to all jobs.

Another difference is the level of involvement that HR departments had in operational decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizations with established remote working were far more involved in the process (almost 90% reported ‘Fully’ participating) than those without (41.7% respectively).

Respondent Similarity – Clustering

Using the replies provided by the participating countries in the survey we can see how similar they are in their views and implementation on remote working and their response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Based on a similarity and clustering analysis three distinct clusters emerge:

Cluster No.1 comprising Belgium, Germany, Estonia, United Kingdom, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Finland features excellent overall response satisfaction, previous experience with remote working, high HR involvement in decision making, significant means to apply remote working, and highly positive attitude towards remote working for use in meetings.

Cluster No.2 comprising Bulgaria, Latvia, Belarus, Moldova and Romania features the second best rates (after cluster No.1) in overall response satisfaction and in positive attitude towards remote working for use in meetings.

Cluster No.3 comprising Armenia, Greece, Spain, Malta, Norway, Russia and the Czech Republic features the second best rates (after cluster No.1) in previous experience in remote working, level of HR involvement in decision making and in means to apply remote working.

Conclusion

The survey showed that remote working, even in the occasions that was introduced for the first time, functioned quite effectively. It also showed that there are productivity gains from remote working but under the condition that it is designed correctly.

Therefore, it is of high importance to understand its challenges and take them seriously into consideration so that it can become more sustainable for the future, more efficient in terms of productivity and more appropriate for the well being of the employees.

[1] The countries which participated into the survey are: Armenia, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Moldavia, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, United Kingdom.

How are we paying for this economic crisis? EU’s new budget

Clara Volintiru and John D’Attoma

The EU is stepping up to the economic challenges posed by Covid19 with a recovery plan titled Next Generation EU of 750 billion euros. Together with the new multiannual EU budget it all rounds up at almost 2 trillion euro, which are to be dispersed through grants and loans to member states. As member states rally in solidarity, mutualizing debt, a looming issue persists: will the next generation foot the bill? Will it be worth the burden?

There is very little room for the austerity-based approach of the previous crisis which has left governments across Europe with little political capital. The continent shifts from the concept of European sovereignty to that of European solidarity, but leaders stumble on how to proceed with the European project. As always, it is a question of money: will countries pool together their resources and further the political union, or will they continue to stand apart, cautious of their national electorates’ reaction to what is characterized by many to be a “Hamiltonian moment” for Europe? Interestingly enough, recent polls show Europeans more inclined to support further integration, as the pandemic has convinced many of the need for more EU cooperation. And this is all about common action in the end – the ever-elusive convergence and cohesion across all member states, North and South, East and West. The move towards common action in the health sector in the context of the Covid19 could be the very thing to jumpstart the next phase of a more political EU.

Given the current context, with the motto of standing “together for Europe’s recovery”, Germany seems forced to take the lead and pay the bill, as the single largest economic power in the EU. But it is highly unlikely it will do so without a clear contingency plan on public finances at the national level.

Global public debt is expected to reach an all-time high, exceeding 101% of GDP, and the average overall fiscal deficit is expected to soar to 14 percent of GDP in 2020, according to the latest IMF projections. For many EU countries, the year could close with double-digit public deficits—for Spain and Italy for sure, but also likely for France, Poland and Romania.

Therefore, a new strategy to reign in public deficits is needed. Rather than slashing spending, another approach could be to strengthen tax administrations and fiscal collection through digitalization and tax administration reform. At the EU level, estimates placed the tax gap at approximately 825 billion euros per year, and in many EU member states tax gaps exceed healthcare spending. In contrast to Northern states, Southern and Eastern European countries have extensive tax gaps that could be addressed through digitalization and public administration reform. In many of the newer member states, tax revenues are only about a third of their GDP.

Even before the Covid19 pandemics, the tide was turning towards a new digital era for fiscal authorities. Governments play a pivotal role when it comes to digitizing payments in an economy—from tax collection to shifting government wages and social transfers into accounts, governments can lead by example and play a catalytic role in building a digital payments infrastructure and ecosystem where all kinds of payments—including private-sector wages, payments for the sale of agricultural goods, utility bills, school fees, remittances, and everyday purchases—are done digitally. This process yields better traceability of payments, thus countering fiscal evasion, and it has shown its merits in many European countries. However, such solutions are difficult to implement in contexts of ample subnational disparities of development as in the case of larger Central and Eastern European countries like Romania and Poland or Southern countries with consolidated informal traditions like Italy or Greece.

Institutional capacity is clearly another driving factor of fiscal collection. In our large scale behavioral experimental study of Europe and America, we found that cross-national differences in fiscal compliance could be associated with institutional differences. It is time EU realizes that general conditionalities do little in the way of convergence, and realistic technical assistance packages should be geared towards meaningful institutional reform and harmonization of practices across the EU. This is particularly important for countries with a poor track record on state capacity in Eastern or Southern Europe. It is also useful for insulating these funds from political opportunism and clientelism in countries with authoritarian tendencies such as Poland and Hungary.

We understand that improving administrative capacity is not a panacea for the tax gap and that any reform plan must realistically account for a number of other factors, such as the number of SMEs in an economy, informal norms, political opportunism, and poor institutional capacity. And the stakes are literally much higher in the context of the unprecedented financial package put forth by the EU.

Clara Volintiru is an Associate Professor at the Bucharest University of Economic Studies (ASE) and a GMF Rethink.CEE fellow 2020.

John D’Attoma is a Lecturer at the University of Exeter Business School and a member of TARC.

The Chancellor’s summer economic statement

By İrem Güçeri, Centre for Business Taxation, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

On Wednesday, the Chancellor announced a £159 billion package to tackle the challenges arising from the Covid-19 crisis. In this blog, I will discuss three of the Chancellor’s announcements: the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) phase-out plan, the series of policies under ‘Supporting Jobs’,[1] and the VAT reduction for the hospitality sector.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has conducted a survey on the impact of Covid-19 on UK businesses which sheds some light on their state as we move from a phase of acute disruption due to the crisis to one of initial recovery,[2] and shows which policies have been used most. The latest results, for the first half of June 2020, show that 95% of respondents (in both ‘SME’ and ‘large’ categories) used the furlough scheme, and more than half the respondents benefited from VAT payment deferrals. The response in relation to the furlough scheme is in line with evidence from Norway: Alstadsaeter et al. (2020) find that the most important schemes during the initial phases of the Covid-19 crisis have been those that relate to employer-employee relationships and in general, support the labour force.

A paper I co-authored with colleagues at the CBT, as well as Michael Devereux’s earlier blog, argue that the transition out of the furlough scheme should come partially in the form of employment subsidies, and in combination with a partial furlough applying to workers on reduced hours. Return to work on reduced hours is now supported within the furlough scheme, a welcome adjustment in line with the idea of a gradual phase-out rather than an abrupt termination of the scheme. The £1,000 Job Retention Bonus for retaining workers from October through to January is broadly in line with the employment subsidy that we proposed. However, it is not clear that the size of the subsidy is high enough to induce businesses to re-employ furloughed workers. And the fact that it is a lump-sum also means that it will be more effective in helping the re-employment of lower paid workers.

For a worker employed full-time at the minimum wage, the three-monthly salary amounts to around £4,200, in which case the employment subsidy is below 25% – which may be too low to have a significant impact. But the rate of support falls further as pay increases, making it less likely that businesses will retain higher-skilled employees and employees in more skill-intensive jobs. Overall, the employment subsidy is a welcome development, but at the current rates of support, some businesses will inevitably lay off workers with job-specific skills from October onwards. Facilitating matches between the newly-unemployed skilled workforce and vacancies may entail substantial costs. After the layoffs, re-training will be very important for these workers to return to employment.

As these workers are laid off, the demand for such workers may not pick up quickly, given the uncertainty that still prevails in the economic environment. The package allocates £2.1 billion to the Kickstart scheme, targeted at 16-24-year olds from disadvantaged backgrounds, and another £1.6 billion to apprenticeships, other youth programmes and to expanding the Jobcentre Plus support for the unemployed. Currently, what the package means for the newly-unemployed from October onwards is not spelt-out in great detail, especially for older, more experienced, and possibly higher-skilled employees.

Another major announcement is the temporary VAT rate cut for the hospitality sector from 20% to 5%. In his blog last week, Eddy Tam argued that VAT rate cuts may lead to higher demand by UK consumers, pointing to evidence from an earlier VAT rate cut during the 2008-09 recession. But this crisis is like no other. The Chancellor’s announcements on the VAT reduction and Eat Out to Help Out are very specific and may have arrived too soon.

They may have arrived too soon because the hospitality sector is still facing significant capacity constraints due to the requirement to be socially-distanced environments. That is a supply-side constraint, not a demand-side constraint. Increasing demand may then have little impact on the total size of business of the sector. Targeting the Eat Out to Help Out scheme to weekdays that are normally quiet seems like a small attempt to address this issue.

However the effects of the VAT rate cuts may also help businesses more directly. Studying a VAT rate cut for restaurants in France, Benzarti and Carloni (2019) find that 55% of the proceeds from the rate cut is absorbed by business owners, rather than the customers or the employees. In the current environment, that represents additional support for troubled businesses – even if the stated aim of the policy is to stimulate demand and employment. Second, experience shows that prices are more likely to respond to VAT increases, but they are found to be less respondent to VAT reductions in the same way (Benzarti et al., 2020). If this is the case, a temporary VAT cut might even result in higher prices after the policy ends.

The policies announced by the Chancellor on Wednesday are a welcome step in the direction of supporting a speedy recovery, to maintain otherwise viable UK businesses, and to protect and create jobs. But the Job Retention Bonus may not be of sufficient scale. And targeting very specific activities too soon may generate distortions and tighten government finances without improving the society’s overall welfare, especially if the current constraints are on the supply side rather than on the demand side.

[1] See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-plan-for-jobs-documents/a-plan-for-jobs-2020.

[2] The caveat of this survey is its modest response rate, which remained at around 30% for its first 7 waves so far. Importantly, the responses come from ‘surviving’ businesses, and not from those who had to permanently stop trading.

References:

Alstadsaeter, A., Bjorkheim, J.B., Kopczuk, W., Okland, A. (2020) “Norwegian and US policies alleviate business vulnerability due to the Covid-19 shock equally well”, mimeo.

Benzarti, Y. and Carloni, D. (2019) “Who Really Benefits from Consumption Tax Cuts?

Evidence from a Large VAT Reform in France” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, February 2019.

Benzarti, Y., Carloni, D., Harju, J, and Kosonen, T. (2020) “What Goes Up May Not Come Down: Asymmetric Incidence of Value-Added Taxes”, Journal of Political Economy, December 2020.

This blog was originally published by the Centre for Business Taxation (CBT) (http://business-taxation.sbsblogs.co.uk/2020/07/13/the-chancellors-summer-economic-statement/

Recent relevant research from the Centre for Business Taxation:

Discretionary Fiscal Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic, Michael P. Devereux, İrem Güçeri, Martin Simmler and Eddy Tam, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, June 2020.

Tax Policy and the COVID-19 Crisis, Richard Collier, Alice Pirlot, John Vella, Intertax, forthcoming.

COVID-19 Challenges for the Arm’s-Length Principle, Matt Andrew and Richard Collier, Tax Notes, Volume 98, Number 12, June 22, 2020.

Chronicle of a Crisis Foretold? Latin America in the time of Coronavirus: Revenues, Growth and Policy Responses.

By Matteo Pazzona, Brunel University London

According to the World Health Organization, Latin America is the current epicentre of the Covid-19 pandemic. While many countries have been able to control the spread of the virus, in Latin America the peak has yet to be reached. Some numbers might help signify the extent of the looming crisis. Brazil is the second country in the world in terms of deaths and confirmed cases. Peru, an early adopter of lockdown measures together with Chile, sits 8th in the inauspicious global ranking of contagions, with more than 240,000 confirmed cases. In Chile, the situation seems to be out of control and it is the 5th country in the world in terms of cases per capita, although testing six times more than Brazil. Mexico adopted a late response and has now more than 22,000 deaths, a number which (as with all these numbers) is probably underestimated. The virus could spread in the region thanks to the high number of informal sector workers, the high level of urbanization and weak health systems, which make the lockdowns measures difficult to enforce. There are success stories too: countries like Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina, and Nicaragua show low levels of cases and deaths, for now at least. Argentina has around a tenth of confirmed cases and deaths compared to Peru, a country of similar population. In Colombia, the city of Medellin acted fast and with the help of technology was able to limit the spread of the virus.

The challenges ahead for governments, and particularly tax authoritiesin these countries, are considerable. The crisis will negatively impact tax revenues directly – through lower taxable income and consumption- but also a decrease in tax compliance, especially from the struggling segments of the population. Fiscal authorities will need to need to adapt their tax strategies to accomplish fiscal sustainability and promote economic recovery. According to a recent report, in 2020 the region GDP will decrease by 7.4 %, the largest slump in the world. The two biggest economies, Brazil and Mexico, will have a negative growth of 7.6 % and 8.5 % respectively. The current crisis is happening after a period of low growth which started in 2014, caused mainly by the drop in commodity and oil prices. The current crisis leads to further drops: countries such as Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, or Peru are already experiencing a drastic reduction in exports which is likely to extend for many more quarters. The tourism industry, which represents a significant share of employment and revenues, has also been severely hit.

Besides, the economic structure of many Latin American countries is dominated by small companies (99% according to the OECD) which being less likely to have a financial buffer to survive the crisis, might go bankrupt rapidly. There has been also a significant decrease in remittances flow from migrants working abroad. According to the World Bank, the region will experience a 20% decline in the flow, the highest ever recorded. Financial volatility has also been a constant in the last months, with many currencies devaluating and significant capital flight. The pandemic will also lead to a surge in inequality and poverty, as reported by the World Bank. That is very unfortunate, especially because many countries had managed to decrease their levels in the last two decades. The current crisis will also be costly in terms of human capital accumulation, which will affect the most fragile sectors of the population. All this inevitably will have a significant impact on tax revenues, and the growth trajectory of the economies.

Latin American governments have implemented a wide range of welfare programs to sustain individuals and firms. They have helped vulnerable households through direct transfers or employment subsidies, among others. For example, Brazil extended the well-known and successful Bolsa Familia program and created a new transfer scheme for informal workers. Several countries, for example El Salvador, have helped directly or indirectly the firms through tax breaks, loan instalments, and public credit guarantees. However, the fiscal power of many countries is limited compared to richer ones and the fiscal space is further restricted by six consecutive years of soaring debt/GDP ratio, due mainly to the effects of low commodity prices on government revenues. The large share of the informal economy, 40% according to the OECD, further constrain the fiscal power of the region. Despite this, the countries that managed to create a fiscal buffer in the last years and have better access to the financial markets were able to implement more aggressive policies. For example, the fiscal COVID-19 related spending in Peru accounts for 12 % of the GDP, 10 % in Brazil, and 7 % in Chile according to IMF data. On the other hand, Mexico will spend between 0.6 % and 1% of the GDP in such measures (depending on the source used). These figures need to be taken cautiously because it is difficult to identify COVID-related expenditures from normal ones. Moreover, tax breaks or credit guarantees are not visible in fiscal accounts.

Fortunately, countries in Latin America will receive international financial help. The Inter-American Development Bank increased the loans to countries by $3,300 million, plus $5,000 to sustain the private sector. The World Bank Group committed to providing $160 billion to alleviate the health, economic, and social impacts of COVID-19 around the world and a big part of these funds will go to the region. The IMF has also secured a significant amount of money to help many countries in the region.

COVID-19 and AFRICA: The World Should Take Bold Actions

Christos Kotsogiannis

Professor of Economics, University of Exeter, and Director of Tax Administration Research Centre (TARC)

Michael Masiya

Researcher at The African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF)

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the health and social fabric of society and the economy of countries across the globe. Nearly all countries to date have reported COVID-19 infected cases, but they have followed different trajectories as their exposure to the virus, their response and level of preparedness have differed. Europe and the US have been under a COVID-19 siege, while confirmed cases in Africa are lower but rising, albeit at a slower pace.

As of 21st May 2020, all 54 African countries had reported a collective total of 95,482 cases of COVID-19, with South Africa (18,003 confirmed cases) being top of the list closely followed by Egypt (14,229), then Algeria (7,542). The pandemic is affecting life significantly everywhere, but in Africa, the impact can be more long-lasting and devastating. Africa’s health infrastructure is the least developed in the world. As of April 2020, Central African Republic, for instance, with population of around 5 million, had just three ventilators. Sierra Leone, with a population of 7.5 million and Burkina Faso with a population of 19 million, each had less than twenty. Infant and maternal mortality are significantly high too, signifying the underlying challenges and the pressure on the health system.

African countries are predominantly agriculture-based economies, where populations engaged in agricultural activities live hand-to-mouth, with limited access to sustainable income. Estimates show that Africa has the highest rate of informality in the world, at 72 percent of non-agricultural employment, and that 94 percent of workers with no education are informally employed. Walking long distances to access basic amenities like water, firewood, and food makes lockdowns impractical in rural Africa (Madagascar, Malawi, Ethiopia and Kenya for example). In a March 2020 campaign to boost access to water in developing countries, the World Vision estimated that women and children in rural Africa walk an average of 6 Kilometers just to access safe water! A prolonged pandemic will also affect crops and therefore food prices. For instance, in Malawi, one of the top three most impoverished countries in the world, food contributes slightly over 45 percent towards headline inflation. Under these circumstances, informal sector workers may hardly appreciate the importance of social distancing rules and global impact of COVID-19.

Revenue mobilization has been an urgent issue over the years, but now with the pandemic it becomes more even more challenging, as governments announce relief measures to ease the impact of the pandemic. Kenya, for example, reduces the standard VAT rate from 16 percent to 14 percent, Malawi offers a 6 month tax amnesty and South Africa provides a tax subsidy of up to R500 per month ($26,60) for the next four months (from April 2020) for those private-sector employees earning below R6 500 ($346).

Whatever measures a country takes, inevitably there will be a loss in production and much-needed revenues. The Africa Purse (2020), for example, estimates that COVID-19 will cost Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) between $37 billion and $79 billion in output losses for 2020. This is due to a combination of effects, ranging from trade and value chain disruption, to disruptions caused by containment measures. Further estimates suggest economic forecast for SSA will fall sharply from 2.4% in 2019 to -2.1 to -5.1% in 2020 due to the impact of COVID-19. This will have a significant impact on the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development which is the most comprehensive blueprint to date for eliminating extreme poverty, reducing inequality, and protecting the world at large. The anticipated recession of Africa economy due to COVID-19 will surely delay meeting the 2030 Agenda targets.

Lack of containment of COVID-19 (and the uncertainty surrounding the behaviour of the virus itself) could also cause displacement of people and increase the migration flows from Africa into Europe. And it will surely worsen poverty and inequality, due to large numbers of fatalities in poorer communities.

World Bank data shows that debt service in 2018 was approximately 2.1% of regional GDP. To service this debt and simultaneously provide for a policy stimulus by redirecting expenditure on health will be nearly impossible. The challenge has prompted discussions in international institutions (World Bank and the IMF) for a bilateral debt standstill, to soften the impact of COVID-19. The G20 too have recognized that coordinated effort is required to support Africa in dealing with the economic and social consequences of COVID-19.

While these are welcome discussions, care of course must be exercised in making sure that the funds are directed for their intended purpose. In some countries, where elections are coming up, diverting funds towards electoral campaigns might be very tempting According to a 2015 report released by the African Union’s (AU) high-level panel on illicit financial flows and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), Africa is estimated to be losing at least US$50 billion annually to illicit financial flows, including fraud, tax avoidance, offshore investments and siphoning of billions of dollars meant for the poor. At the time when the whole world is facing a crisis and the G20 trade some of their stimulus off to Africa, the best way to give back is to enforce the utmost levels of good governance in handling the relief or funds. Beneficiaries must ensure that the stimulus is solely directed towards mitigating the impact of COVID-19.

Recently, 18 leaders signed a letter (see ‘Only victory in Africa can end the pandemic everywhere’, FT 14/04/2020) arguing for a stimulus package of at least $100bn so African countries have enough fiscal space for health expenditure (including, procurement of medical supplies and equipment, building diagnostic capacity and training and improving the health screening of people) but also for mitigating the economic and social consequences of the pandemic. The arguments are well justified. This is not an economic crisis, but a crisis caused by a global pandemic. The world should collectively take bold actions.

Recent Comments