Siam Bhayro

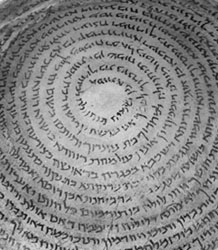

In our department, we have a couple of projects that relate to the study of Aramaic incantation bowls, including the recently launched Virtual Magic Bowl Archive.

At first sight, these dusty little pots may seem of marginal interest at best, particularly for theologians and Bible scholars, but it turns out that they are a really big deal. For a start, they are the best epigraphic source we have for studying the everyday beliefs and practices of the various Christian, Jewish, Gnostic, Pagan and Zoroastrian communities of the near east in Late Antiquity and in the early days of Islam. While manuscript sources have been copied and subjected to repeated editorial activity over the centuries, often in order to present official histories, these humble vessels come straight from Late Antiquity and show us what we were never meant to see.

For example, we see the everyday domestic and health concerns of women, often in very intimate terms. One bowl shows us that a lady called Gista, daughter of Ifra-Hormiṣ, who was almost certainly Zoroastrian, was concerned about the ill effects of erotic dreams. She visited a Jewish scribe to whom she confided her anxieties and who then wrote a text on a bowl for her that sought to counter demons who: ‘resemble human beings – to men in the form of women and to women in the form of men – and with human beings they recline by night’. This shows a remarkable level of cross-community interaction, beyond what the official histories would have us believe, and also allows us an interesting glimpse into what is effectively late antique psychotherapy.

The bowls are written in a variety of types of Aramaic, each reflecting the creed of the scribe – Jewish Aramaic, Mandaic, and Syriac. Yet we see that these scribes, representing the educated elites of their respective communities, were in some way collaborating in the field of magic. For example, the following Jewish text occurs in a Syriac bowl: ‘I cast a lot and take it, and I perform a magical act – that which was in the court of Rabbi Joshua bar Peraḥia’.

The Jewish Aramaic bowls in particular contain many biblical quotations, most of the time in Hebrew. In a number of cases, these references are not preserved among the Dead Sea Scrolls, so the bowl quotations represent the earliest attestations of these verses in Hebrew in any known source. A recently published volume of bowls contains the following such attestations: Exod 15:3; Num 9:23; 10:36; Deut 28:57; Pss 10:16; 24:8; 32:7; 116:6.

In some form or another, I have been working on Aramaic incantation bowls since 1997. As things stand, we have published one volume out of a projected nine on the bowls in the Schøyen Collection, and we are also working on other collaborative projects, e.g. a projected four volumes on the bowls held in the Pergamon Museum (Berlin). In other words, it is possible that the rest of my working life will be taken up in some way with editing and publishing bowls, and explaining their wider significance. So please excuse me if, from time to time, I seem a bit absent as I wander down the corridor in Amory muttering ‘bowls, bowls, bowls’.

Siam Bhayro is Senior Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies,

Department of Theology & Religion, in the University of Exeter