Susannah Cornwall

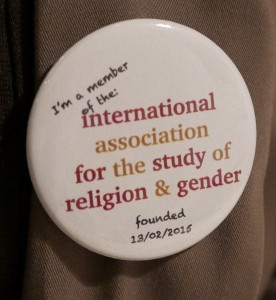

It’s always exciting to be present at the start of something new, and it was a real honour to be invited to be a conference respondent at the Religion, Gender and Body Politics: Postcolonial, Post-secular and Queer Perspectives conference in Utrecht, where the brand-new International Association for the Study of Religion and Gender (IARG) was officially launched. Utrecht is also famous for the Domtoren (the tallest church tower in the Netherlands), and the Dick Bruna Huis, a museum celebrating everyone’s favourite rabbit character, Miffy!

The IARG is newly-minted, but there have been a series of smaller meetings leading up to this conference over the last couple of years. They’ve taken place at SOAS in London; in Oslo; in New York; in Turku, Finland; in Ghent, Belgium; and in Utrecht.

The project has been co-ordinated by Prof. Anne-Marie Korte, Professor of Religion, Gender and Modernity at Utrecht University, and Dr Adriaan Van Klinken, Lecturer in African Christianity at the University of Leeds along with a team of able assistants.

The project has already launched the open-access journal Religion and Gender, which is already publishing significant work in this interdisciplinary area, and is a great first stop for reviews of new books on gender and religion. This last conference featured presenters from the USA, the UK, the Netherlands, Norway, Germany, Spain, Canada, India, Belgium, Italy, Finland, Japan, South Africa, Ireland, Hungary, Turkey, South Korea, and Morocco. The research focus in various of the papers included Indonesia, South Africa, Kenya, the former Yugoslavia, Ireland, Iran, China, Poland, Turkey, Morocco, Zanzibar, Italy, South Korea, Lebanon, and – of course – the Netherlands – so it was a truly international affair.

The keynote lectures were from a range of disciplinary perspectives. Prof. Minoo Moallem, Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at UC Berkeley, spoke on ‘Sensorial Visuality and Material Cultures of Shia Islam’. Her paper focused on the example of coffeehouse painters in Iran, and the influence in sensory and mimetic terms of art and performance on subjecthood and citizenship. She pointed to the hybridity of present-day Iranian culture, noting that Iranian Shi’ism has never been aniconic in the way that many other manifestations of Islam have. This is, of course, directly relevant to many of the discussions taking place across Europe at the moment in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo shootings.

Prof. Ulrike Auga, Professor of Theology and Gender Studies at Humboldt University in Berlin spoke on ‘Confessions of the Flesh: The Performative and the Material Body in the Documentary Fake Orgasm’. This was a fascinating discussion of disclosure and the confessional, using clips from a documentary about the transgender performance artist Lazlo Pearlman, who seeks to bring about self-reflexivity in his audience members and is dismayed when they simply wish to ask him questions about his own body and identity. Pearlman remains adamant, however, that performance can create possibilities for the emergence of new knowledges and contributes to a new social imaginary.

Prof. Sarah Bracke, Associate Professor of Sociology at Ghent University in Belgium, and Visiting Fellow at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard, spoke on ‘A Nonsovereign Subject and her Body: Thinking Piety, Gender, and Embodiment’. Bracke engaged with Saba Mahmood’s book Politics of Piety, published ten years ago this year, and noted that whilst most commentators have focused on Mahmood’s discussion of agency among (mostly female) female adherents to religious traditions, her account of embodiment has been given much less attention. Academic sociology, noted Bracke, has often studied religion as an object, an “other”. Drawing on her ethnographic work on vocation in Italy, Bracke commented that vocation is often gendered as feminine and “receptive”, but might be reclaimed for queer self-actualization via the development of agency in community.

Prof. Scott Kugle, Associate Professor of South Asian and Islamic Studies at Emory University in Atlanta delivered a paper entitled ‘Islamic Reflections About the Body Beyond Heteronormativity’. He argued that it is possible to interpret particular Qur’anic passages as already pointing to sexed and sexual diversity within creation. He pointed to four elements of personhood in Islamic theology: sura or outer form; shakila or inward personality; tabi’a or material genetic inheritance; and fitra or original nature. He noted that many LGBT Muslims have appealed to the term fitra in Qur’an 30:30 as an invocation of the theme of not altering what God has created.

Prof. Sarojini Nadar, Professor of Gender and Religion at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa spoke on ‘Negotiating the “F-words” in Academia: “Faith” and “Feminism” within Contexts of Gender-Based Violence’. She argued that, in some academic fields, scholars are told that they must present their narratives in acceptable ways, and that this has led to feminist and faith-based work being sidelined. The erasure of discourses of violence in sacred texts leads to a lack of attention to the violence against women and minority groups that is still perpetuated.

The paper I personally found most stimulating was that given by Prof. Yvonne Sherwood, Professor of Biblical Cultures and Politics at the University of Kent: ‘The “Hagaramic” as a Provocation for Euro-American, “Judeo-Christian” Parochialism: Surrogate, Rogue, Resident Alien, Foreign Body’. She noted that “Abrahamic” is often used as an “anxious” successor term to “Judeo-Christian”, but has many of the same problems. The “Abrahamic” is, she suggested, a form of regulated plurality in which Jewishness and Islamicness are written into Europeanness, but always on Anglophone and culturally Christian terms. Sherwood posited that the shared genealogies of Judaism, Christianity and Islam might be better characterized as “Hagaramic”, after the resident alien woman whom the biblical Abraham took as his concubine when he was unable to conceive children with his wife Sarah. The introduction of Hagar queers the Israelite genealogy and creates its own complications and a new set of lacks and desires. The “Hagaramic” thereby detracts from the primacy, oneness and uniqueness of the Abrahamic name.

There were also a total of 40 short papers; poster presentations with a prize of €200 for the best project (deservedly won by Matthias Deininger of Heidelberg University in Germany for his project “Preserving the Heteronormative Status Quo: Public Morality, Evangelical Christians and the State in Singapore”); a special plenary session on disability in the academy; a “political forum” with debates on state regulation of boys’ religious circumcision and on the ethics of surgical intervention for intersex infants; a conference dinner at which the Association was launched; and lots more excellent Dutch food and drink!

The full conference programme is online here, and there will soon be further information on the same website about the ongoing work of the International Association for the Study of Religion and Gender and how to join it. Within the fields represented at the conference, “gender” is often shorthand for “women”, with little attention given to variant sex and gender, genderqueer and non-binary identities, or masculinities. I’m pleased to say that wasn’t the case here: fascinating papers on drag queens in Lebanon, waria trans people in Indonesia, and Butchi lesbian gender expression also in Indonesia, among others, meant that a broader range of gender experience was examined. Responding to the conference as a whole was a challenge but also a great honour, and I was delighted to be invited!

Susannah Cornwall

Advanced Research Fellow (HASS Strategy)