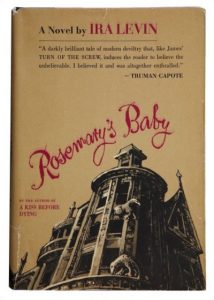

Book: Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1967) – made into a film the following year by Roman Polanski. Both were extremely successful.

Accuracy:

Not very. Leaving aside the whole question of how likely it is that you’ll end up sharing a New York brownstone with a witches’ coven who get your husband to impregnate you with the Devil’s seed, and prevent you from getting a medical second opinion that might dissuade you from going to term with the Son of Satan, this is a very perfunctory account of childbirth (and recovery). The birth scene is eclipsed by Rosemary’s dawning realization that she is at the mercy of her husband, her neighbours (who are really witches), and her doctor (also one of the coven); every so often she remembers to have a contraction; then they give her an injection that makes her contractions feel ‘faint and disconnected from her floating eggshell head’. And that’s it, until she wakes up to feel ‘pain between her legs like a bundle of knife points’ (ouch). Post-partum, she takes to a breast pump with highly unrealistic ease.

The description of quickening (‘Something moved in her […] where nothing had ever moved before. A rippling little pressure’) is charming and accurate.

Empathy: Total. Rosemary focalizes every scene, so we see her vain, manipulative husband and her repulsive neighbours through her sympathetic and forgiving eyes; but we also share her reluctant but determined recognition that they are all plotting to subvert her pregnancy (wrongly, she thinks they’re planning to use her infant as a blood sacrifice to Satan).

Style: Fast-paced and highly readable (unsurprisingly selling 5 million copies within a year of publication).

The Pregnancy Test: Is this a book about the power or the vulnerability of pregnant women? Rosemary’s Baby doesn’t give us any new insights into how pregnancy feels; Rosemary is a very typical, nice young woman with vaguely Lamaze-inspired aspirations for natural childbirth. But her battle to control her pregnancy and to protect her child could be read, as Karyn Valerius proposes in her informative article “‘Rosemary’s Baby’, Gothic Pregnancy, and Fetal Subjects“, as a reflection of American women’s struggle to decriminalize abortion, particularly in the wake of the thalidomide tragedy. Roe vs Wade was not passed until 1973. P.A. Boswell in Pregnancy in Literature and Film (2014), although she discusses the film rather than the book, argues that the former provides ‘our first glimpse of a mature pregnancy narrative in contemporary film: pregnancy reveals the power of the pregnant woman’ (120). It’s true that in the book, Rosemary ultimately accrues status from her devotion to the child and her undeniable position as Satan’s Mother, but her influence is back-dated: during her pregnancy, she is tricked and manipulated. I like to read this novel as an updating of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s seminal 1892 “The Yellow Wallpaper”, in which a (childless) woman slowly goes mad, well-meaningly neglected by her husband and doctor as she becomes increasingly convinced that a woman is trapped behind the yellow wallpaper in her room. In Rosemary’s case, there really is a woman behind the wallpaper; she doesn’t have to go mad to become free. She does, however, have to have a child with claws, horns, and golden-yellow pupils.

Verdict: Positive.