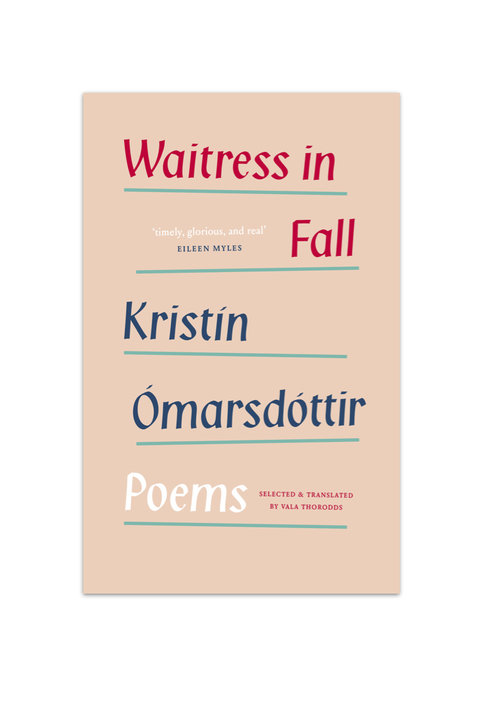

I’m delighted to welcome Laurie Garrison to the blog today, with a review of Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s Waitress in Fall. Laurie is the dynamic organizer of the Women Writers Network, and you can find her full bio here.

In Iceland, Kristín Ómarsdóttir is about as famous as poets can be: she has been nominated for or won a long list of awards, including the Icelandic Women’s Literature Prize; she is a successful dramatist; and one of her novels has been translated into English. Until now, however, none of her poetry has been available in English. It is therefore exciting that a selection of poems written across her entire career has now been translated as Waitress in Fall by fellow Icelandic poet Vala Thorodds, founder of Partus Press. These poems take the reader into another world, one that is rebellious, unexpected, humorous and that (I think) has more in common with French surrealism than most of the poetry being written in English at the present moment.

Take the poem “Lemon Breast”, for example. The mundane genre of cooking instructions is transformed into an erotic absurdity:

Slice the lemon into two equal halves

on the kitchen table but take

one half into your room

and squeeze a little of the liquid

over the brown

soft

half-asleep

nipple.

Lick the drops that trickle down the breast

before the lips are moved

to the top.

Lick first then suck.

When the taste fades

repeat.

Slightly cringeworthy, slightly humorous, reading Ómarsdóttir’s poetry takes me right back to my undergraduate days of studying French surrealism, especially the surrealist theatre where the odd and the unnerving were also comical and entertaining.

As I worked my way through the collection, I decided to remind myself of some of the authors and titles of surrealist theatre that Ómarsdóttir seemed to have so much in common with. So I consulted my prized collection of French books, which I knew to be basically intact despite a transatlantic move and a post-academic career purge. As I looked through the titles, I remembered Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, Roger Vitrac’s Victor, ou les Enfants au Pouvoir, and Eugène Ionesco’s La Cantatrice Chauve surprisingly vividly. Ómarsdóttir’s poems do indeed have much in common with their style of writing: the characters’ absurdity, the seemingly subconscious associations and swift shifts of attention. But…where were the women writers? I started scanning to see if there was a single woman writer on my French shelf, let alone a surrealist. Marguerite Duras’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour was the only text by a woman on my shelf.

I don’t know if undergraduates are taught a more diverse curriculum in French literature classrooms these days, but we are certainly facing a similar problem in the world of translation. If we consider just how few texts become well-known enough or popular enough to be translated into English and then that women have only authored one quarter of translated texts, there is a glaring woman-shaped hole in the translation-publishing industry. This is precisely why we need a translation of poetry like Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s in the English language. She has taken a historically male-dominated form and made it very female. Her explorations of female identity do not so much challenge the status quo as annihilate it in order to rethink everything about the structure of the world.

Ómarsdóttir has virtually said as much herself in an interview with The Rumpus. In reminiscing about the types of things children read at school, where people behave as expected in a highly constructed, conservative reality, she asserts that her work as a whole is written in opposition to this: “I’m against the reality, the designed reality. I am against the structure of our world, which seems to be raised by violence”. In so many of Ómarsdóttir’s poems, violence either lurks in the background or we see clear evidence of it. In the eerie poem, “Three Poetesses”, for example, partially clothed women sitting around a table are joined by a man in a “pirate sweater”. We do not see literal violence but there is a confident possessiveness about the arrival of a man who joins them without a word.

He touches one of them and we are told that they are all dead, “though they await his kisses”. The waiting and the expectation of affection suggest a commentary on patriarchy: they are bound by the awkward relationships created by this structure. They are dead because their roles under patriarchy are prescribed and unrealistic. The man ominously carries the “touched one” off: a simple touch establishes enough dominion that he can do what he wants with her body, her mind being conveniently elsewhere. The oddity of the scene forces the artificiality of the underlying patriarchal structures to the surface: violence is not openly visible, but its consequences are clear. Significantly, the women are “poetesses” now silenced in death, their bodies at the mercy of a man.

In other poems, such as “headless morning” there is much more overt evidence of violence:

early one morning you receive in the post

the head of a man

damp with blood

on the doorstep

Being an English-language reader of these poems, I cannot help but make the connection with the sagas, where beheadings, revenge killings and other forms of violence are simply part of the fictional landscape. The poem is written in the second person, pushing the reader to consider themselves to be in the place of the receiver of the head: “who wishes me ill?/ you think at the same time as you/finger your neck”. At the end of the poem it is unclear what fate “you” have met: “the sun and the morning songs of the birds/empty what’s left of the consciousness”. The emptying of consciousness could be permanent or it might not be. In societies that are founded on revenge killings and vigilante justice, it is unclear what the fate of either the transgressors or innocents will be. Let’s bring this into a more recent historical moment, where the “you” of the poem must live since the head is delivered by the post that also brings “morning papers” and “letters in envelopes”. Iceland may be celebrated as a democracy that established the first parliament in Europe, but violence was very close to the surface at that time and remains a part of its history.

For me, Ómarsdóttir is at her most feminist when she explores relationships between lovers and between married couples. In “Protein” the speaker obsessively prepares food for her lover in a disturbingly submissive relationship where she “see[s] to it that my man has the guts and the vigour to love me”. Feeding her lover is followed by sex where the protein she has fed him is given back to her in the form of an ejaculation: “I tiptoe along his sated body until I get my portion of the workings of the energy wad/ From morning till night I look forward to the moment when he squirts into me the fluid that I do all I can to co-produce”. No mention is ever made of her role in reproduction or her pleasure in sex other than as the receptacle for his semen. She scoffs at single women: “They never prepare food, they don’t have any boyfriends”. The oddity of these associations—food and reproduction, eating and sex—again brings the artificiality of patriarchal structures to the fore.

One of the most impressive qualities of Ómarsdóttir’s poetry is her ability to envision alternatives to the relationship in “Protein”. In “Mountain Hike on a Summer’s Day”, for example, multiple women share a fiancé:

Female relatives who share a fiancé sit down on the mountain

crest, find dice in their backpacks and throw:

“He is mine, he is mine. He is yours, he is yours…”

But they don’t care who gets him. Chance rules the throw.

The women are in charge here and they subvert gendered behaviours. The relationship between husband and wife is based on chance. Patriarchal and heterosexual structures are undone: women decided the fate of a man and they undermine a presumed possessiveness of monogamous, opposite-sex relationships. There is also the strange conflation of birth and marriage in “ode” when a bridegroom is released from a minke whale:

the armpits of the lads, who on the beach

open the bride with man-sized scissors,

bawl with rage

what I remember as I tore the membrane

off my bridegroom

with long, colourful nails

The bridegroom is born from the whale, which seems to be a bride, but the speaker tears ”the membrane” off her bridegroom. The poem shifts quickly in point of view, disorienting the reader and shocking her with the graphic scenes of birth. This is a sort of group marriage, human and animal, more than two involved, carried out through a gruesome sort of violent act. We are led to ask, is this what marriage is like: a rebirth that is painful, bloody, almost too terrible to contemplate?

We need a female poet like Kristín Ómarsdóttir in the English language. She tears down the usual social structures as if they were nothing, letting us see just how odd they are in the context of other endless possibilities of unfamiliar ways of being, living and relating to other people. I hope the ‘minor’ female surrealists that I’m sure were out there, back when I was an undergraduate studying French, are now taught regularly in university classrooms. And I hope the students are taught to recognize how this form is so effective through its refusal to come to heavy, solid conclusions, preferring instead the playful, unpredictable and occasionally humorous. Indeed, for all her undoing of our comfortable reality, Ómarsdóttir leaves us with laughter in the final words of this collection:

I lie down on the ground

mmm

and laugh with the sky

mmm

laughter