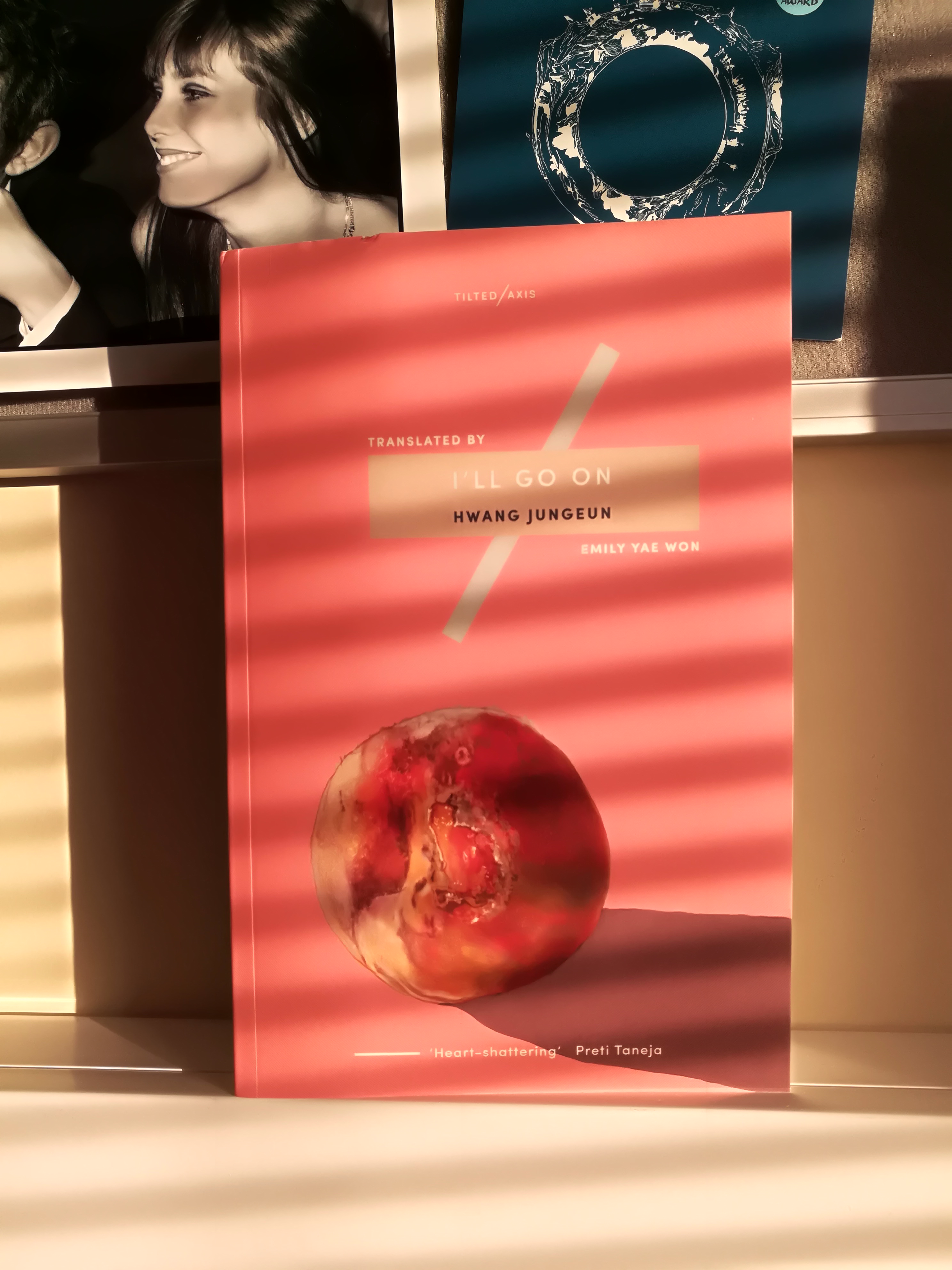

Translated from the Korean by Emily Yae Won (Tilted Axis Press, 2018)

I’ll Go On was the final 2018 release in my Tilted Axis subscription, and I’d been eagerly awaiting it all year. It is the story of sisters Sora and Nana and their family bonds: with their damaged mother, Aeja, who was once brimming with love but has now given herself over to grief, with the enigmatic yet tender boy next door, Naghi Oraboni, and with Naghi’s mother, who fed and sustained Sora and Nana through their childhood. The original title, Soranananaghi, binds the three main protagnists’ names together in an incantation, also incorporating the word ‘sonagi’ (meaning ‘downpour’), and both of these meanings are echoed one drunken evening in three drops of water that Naghi names as Sora, Nana and Naghi, and that join together to make one single body of water. The English title is brilliantly chosen, as it is a phrase repeated like a refrain throughout the book: “I’ll go on” is the epitome of the characters’ determination to live out their lives, resigned to not feeling happy. This is far from being the only example of Emily Yae Won’s deftness in the translation: there are many references to the characters that make up the Korean names, and her incorporation of these never feels heavy-handed or “textbook-like”. I always find it hard to imagine the translation process from a language I know nothing of and a culture I know little about, but this translation seemed to me to keep all the cultural importance of the original, and some of the linguistic features, while still ensuring it was a smooth read in English.

I’ll Go On is narrated in four parts: Sora, Nana and Naghi all take their turns narrating, and then Nana takes over again for the short final section. I have come to greatly enjoy stories with multiple narrators, and one of the things I like about this technique is exemplified brilliantly in I’ll Go On: viewing the same event from different perspectives. The meeting of Sora, Nana and Naghi as children is recounted by both Sora and Naghi, likewise the revelation that “single-member tribes do exist in the world, you know”; an incident when Naghi strikes Nana to remind her that “forgetting, that’s how people turn monstruous. It’s how you become oblivious to other people’s pain” is remembered by both Nana and Naghi, and tense conversations between Sora and Nana are related by both sisters.

At the heart of the story is Nana’s pregnancy: Sora, the older sister, has always looked after Nana, and now feels that Nana has betrayed her, bringing another life into their family unit. Sora resents the pregnancy but tries to be kind; Nana resents Sora for trying to be kind. Sora’s only concept of motherhood is painful: she addresses Nana in her internal monologue with the musing:

“Has Nana set her heart on becoming a replica of Aeja?

Is that it, Nana.

You want to be another Aeja?

Fall in love like she did, and make a baby, and then have the baby, all so you can turn into an overbearing mother?”

As for Nana herself, she struggles with her (lack of) emotions towards the baby growing in her womb: she likes the father well enough, but does not want to marry him, and does not want to form an attachment to her child:

“When it comes to love, that seems about the right amount of emotional involvement: to be able to soon get back on your feet no matter what occurs. Where whether by mutual agreement of by one-sided betrayal or because one of you vanishes into thin air overnight, the other can manage to say, in due time: I’m fine. That seems about right. Even once the baby is here, Nana has decided that that will be the extent of her love for the child and for Moseh ssi.

Pouring all your heart into love as Aeja had done – that level of devotion is what Nana wants to guard against.”

Love is an emotion that can turn sour, that can become overwhelming grief, that can leave you a husk, and neither Sora nor Nana want this kind of love to befall them. They prefer recognisable parameters: companionship, shared memories, walls around the heart. And yet, it is in her attitude towards her unborn child that Nana realises with horror how like her own grief-hardened mother she is becoming: “It dawned on her that having been so intent on her own pain, it hadn’t occurred to her to consider the unequivocal anguish now presented before her. And that this made hers the closest likeness to that heart which Nana wholly detested, namely, Aeja’s heart.” The selfishness of Aeja’s pain, the way in which it closed her off to the pain of others, including her own children, is replicated in Nana – and yet this is not portrayed in some moralistic, daughter-understanding-the-mother way, but rather to show the terror of a child whose mother would prefer to leave the world than care for her, on realising that she too has allowed herself to become so consumed by pain that she cannot see the pain she is inflicting on others. And so we see a cycle: of life, love, resentment, and of the ways in which all three main characters are trapped in a past they cannot set free. This is reflected in Aeja’s repeated questioning of Nana about her pregnancy: Aeja chants “Are you happy? Are you happy? Are you happy?” without waiting for an answer, and Nana listens to “the question that’s being repeated over and over like a curse.” Aeja’s lack of happiness in her own life did not prevent her from wanting happiness for her children, but she fails to see that it is her own behaviour that has wrung out all possibility for happiness from them.

The main emotional connection the three narrators share comes through food: they were all nourished through childhood on the food prepared by Naghi’s mother, Ajumoni, a hardworking widow whose only desire in life is to have a grandchild. Just as it was Ajumoni who fed Sora and Nana through their childhood (“They were the plainest of lunchboxes. Plain and commonplace. And yet to have contained so much in such a compact form is nothing short of immense”), so it was also Ajumoni who gave Sora and Nana the maternal love they lacked in their own home, and it is her food that sustains them even as adults, when they gather together to make dumplings, setting their differences aside as they work together to prepare a feast, the taste of which embodies for Nana “The longing, the delight, the tenderness, the fear, the loneliness, the regret, the joy – all muddled, all at once. All one big mess.” Ajumoni’s food defines both childhood and home for Sora and Nana, to the extent that “no matter what delectable and fine food they may come across now, anything that’s not of this home is simply – for Sora and Nana both – other, the taste of not-home.”

Hwang is adept at crafting profound philosophical reflections in the quietest of ways: the fleeting nature of human life within the vastness of history is made evident in the assertion that “the world’s end will only befall us gradually, and this will give Nana time to think properly about things”; the overwhelming nature of pain is given shape in Naghi’s description of Aeja’s widowhood, when he acknowledges that “over a lengthy stretch of time, she has steadily, inaudibly, fulfilled her pain and become whole. She has hauled her pain over herself, covering herself entirely with it, like a carapace”; the physical depth of love is evident in Naghi’s claim that “This sensory memory is a yearning, and will never be erased. If it is to be rubbed out, it will be the last memory to go, It will leave me only in my final moment”, and perhaps Hwang’s characters are best defined by Nana’s conclusion about human life: “People are trifling, their lives meagre and fleeting. But this, Nana thinks, is also what makes them loveable”. These are some of my favourite lines from the novel, and show the lyrical beauty to be found within it. What could be a fairly depressing story is raised to a thing of crystalline incandescence because of the sensitivity and humanity with which both author and translator craft this work.

The line that most struck me and lingered on in my memory is one that I wish I could shout out to everyone I pass, to those who are close to me and those who are not, to friends and foes, to world leaders, the people who vote for them, and the people who oppose them. And I’m going to leave this line as the last word, in the spirit of the #WiTWisdom pledge that I mentioned last week: “Don’t erase things from the world just because you are incapable of imagining them.”