Ros Schwartz is an award-winning translator from French; she has translated over 60 titles, and in 2009 she was made Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres for her services to literature. Her latest work, a translation of Selfies by Sylvie Weil, was published by Les Fugitives earlier this year.

Your recommendations for how to pitch works will have been seen by many emerging translators; how do you find new works to translate, and how do you choose publishers to pitch your translations to?

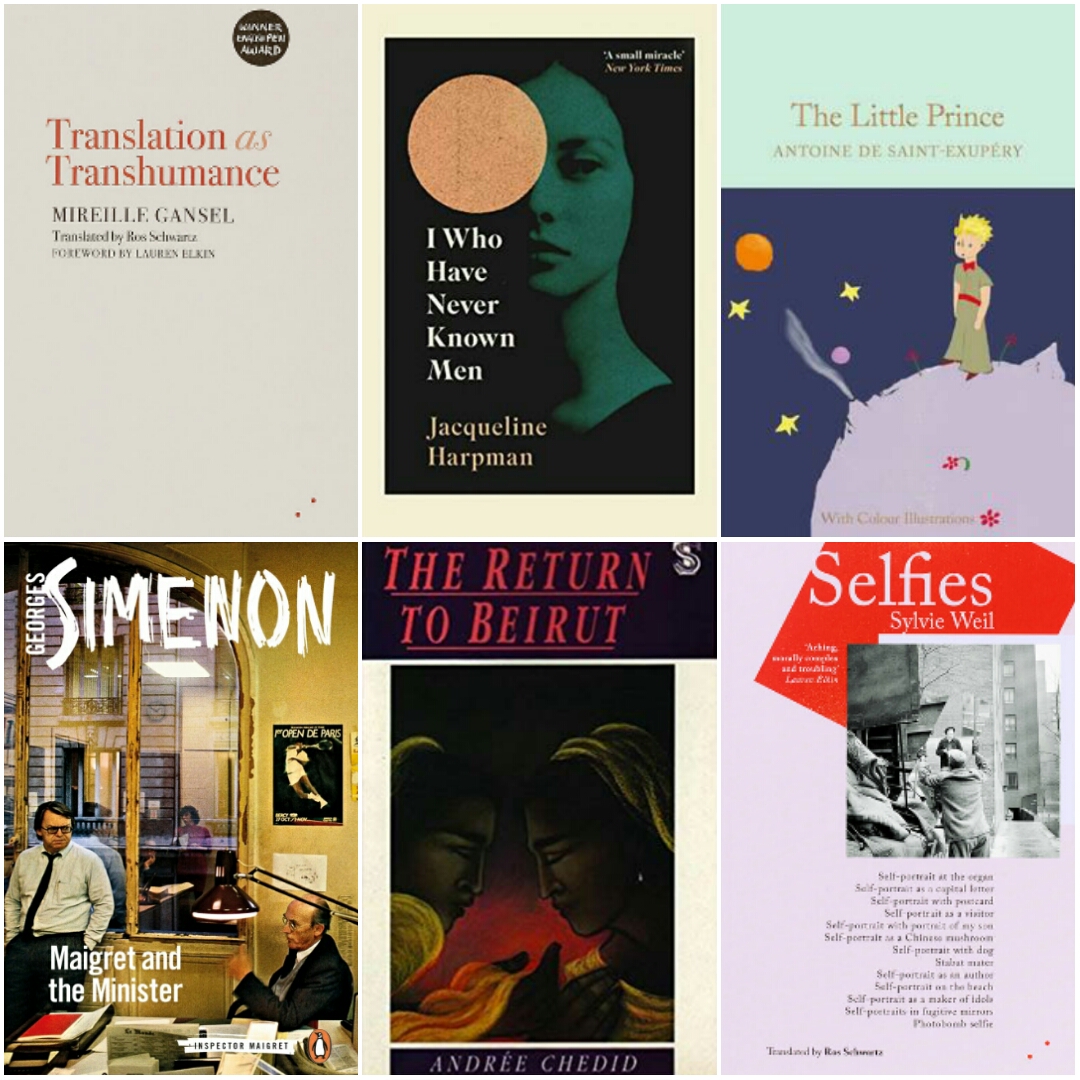

It’s not something I do very often these days. That’s how I got started, and all my pitching recommendations come out of my own mistakes! Now I only pitch when I find a book that I’m completely passionate about because it’s incredibly time-consuming writing to publishers, translating the sample, and so on. I think with Translation as Transhumance [by Mireille Gansel] I probably spent more time pitching it than I did actually translating it. You can only do that for one book every ten years, when a book really grabs you and you’re just so passionate about it that you feel as though the book was written for you to translate. Then you can put in all that effort.

You found a home for Translation as Transhumance with Les Fugitives. What made you choose to place it there?

The whole story of this book – and I’ve written about it in my Afterword – is one of extraordinary serendipity, where you know that something is just meant to happen. The book was sent to me by a Nick Jacobs, who is a retired publisher and a friend of [author] Mireille Gansel. He wanted to get the book translated, someone gave him my name, and he sent me the book. I read it, completely fell in love with it and said to myself “I have to find a publisher for this.” So I started writing to publishers, and they all said the same thing: that on a personal level they loved it, but it wasn’t commercially viable. This went on for about a year, and I had written to every publisher I could think of at that point. In the meantime Les Fugitives had just started out, and a friend of mine who knew them sent me their first book Suite for Barbara Loden, by Nathalie Léger, translated by Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon. And when I read it I thought “this is my publisher.” So I wrote to Cécile Menon, director of Les Fugitives and sent her my sample translation. She had exactly the same reaction as me. I applied for a French Voices grant which helped me find a US publisher, and my translation was published there by the Feminist Press. It has really struck a chord with readers. A lot of publishers said it was too niche, but I have emails from artists, visual artists, all sorts of people who are not translators and who are moved by the book in some way. It’s got so many wonderful aphorisms about translation but it’s not just about translation or about language; a lot of people have responded to it. And in these current times of insularity and xenophobia, it’s a real antidote. Gansel talks about translation as hospitality, and that’s a really key concept.

Yes, in particular her words “In these times of solitude and solidarities: translation, a hand reaching from one shore to another where there is no bridge” are very timely, aren’t they?

Absolutely. I think that’s probably why a lot of people are very moved by it because it really says everything that needs to be said.

The next book that you published with Les Fugitives also focuses on the imbrication of personal experience and wider histories. What drew you to Sylvie Weil’s Selfies?

Cécile offered it to me. She acquired it and she sent it to me in 2016, just before Christmas, and I fell in love with it. And that’s something I have to say about women writers: it hasn’t happened to with any male authors but with both Mireille and Sylvie I actually fell in love with the person. I read Sylvie’s book over Christmas and I was so excited by it; she’s got a dry, ironic sense of humour and we connected on the humour level. I think empathy is essential for a translator. And with both Mireille and Sylvie I felt that empathy.

What do you perceive as the greatest challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature, and how does this affect who gets published and who gets translated?

Is there more gender bias in translated literature than in literature in general? Who are the gatekeepers? Who decides? Who chooses? Who are the funding bodies? There are gatekeepers at every stage. And interestingly, there are a lot of women editorial directors in publishing. So I don’t know that translation is doing any worse than women’s writing in general. What we can do about it as translators is to seek out powerful books by women writers and take them to publishers. It’s as simple as that. Publishers are busy people: they get bombarded the whole time from every foreign publisher on the planet sending them books for consideration. And the only way we can change things is by actually unearthing brilliant books and bringing them to the attention of publishers. This does happen, it is happening.

Isn’t there a double marginalisation for women writers in translation, because the men are the ones who are going to rise to the top of the pile in their own country, and so they’re the ones that going to come to the attention of foreign agents? What do you think might usefully be done to respond to and overcome such biases?

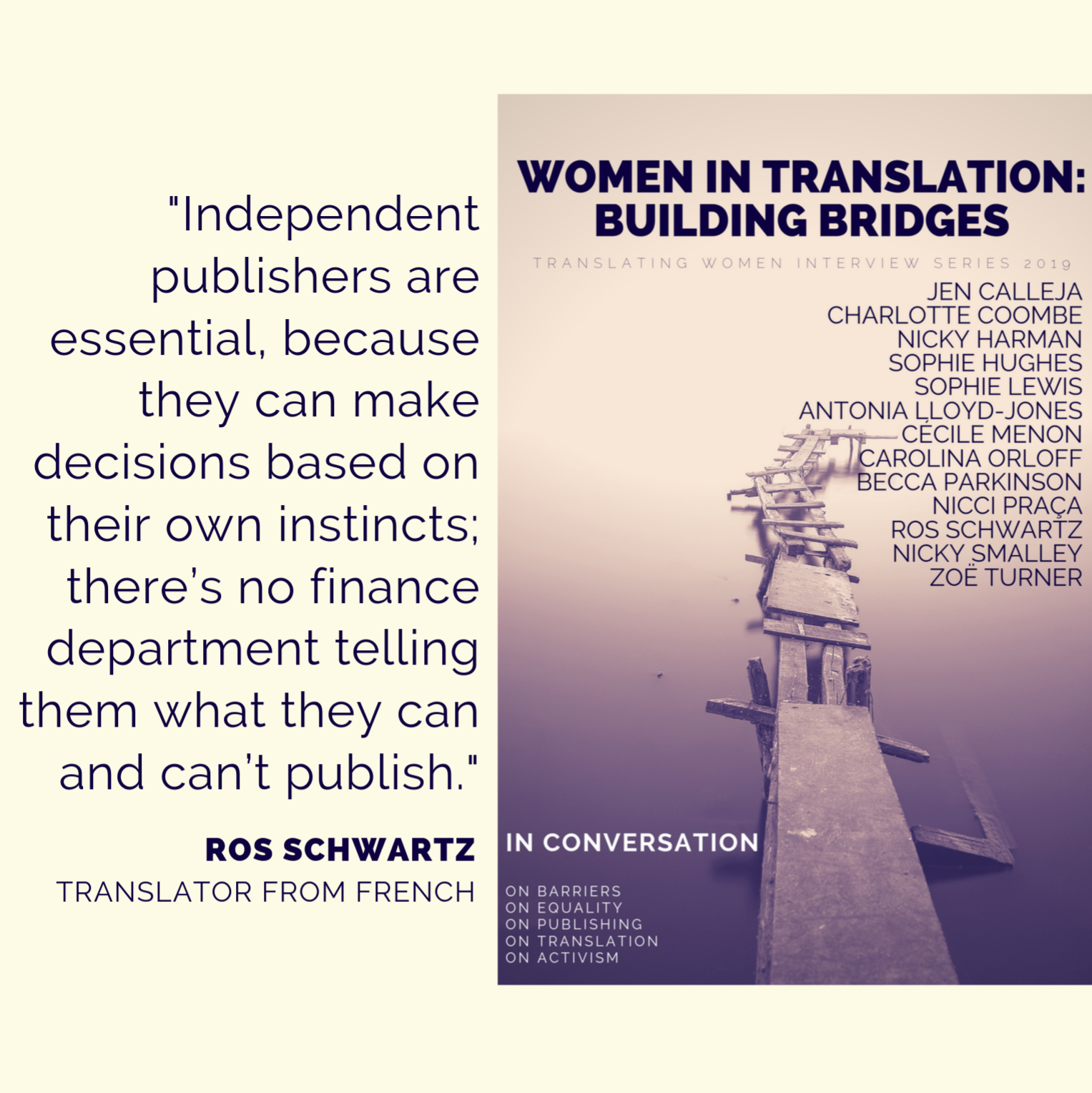

Independent publishers are essential, because they can make decisions based on their own instincts; there’s no finance department telling them what they can and can’t publish. And booksellers are essential as well. For example, the Women in Translation month Facebook campaign has been hugely successful: based on Meytal Radzinski’s research, we collectively decided to have August as “Women in Translation” month. The hive mind came up with a list of amazing books by women that existed in translation and we all just went to our bookshops and said “Hey did you know it’s Women in Translation Month?” and they said “no, what do you mean?” so we gave them a list of books and a logo. They already had many of the books on their shelves and they made special displays, which brought customers through the door. We went back to those bookshops and asked them how the promotion had worked for them, and they said they’d sold lots of books, it brought people through the door and started a conversation. So there are a lot of things that we can all do, little things, to raise consciousness about the issue.

You are involved in a number of networks; what activities do they undertake beyond (and behind) translation, and how do they help translated works towards publication? To what extent would you consider their work as activist?

The PEN Translates programme is absolutely crucial. It’s the main funding programme in this country and the money comes from the Arts Council. PEN is responsible for selecting the books that receive grants. Literary quality is the number-one criterion, but we also consider the book’s contribution to diversity. When the committee meets to discuss which books are going to receive a PEN award, we take into account reports by experts who have read the book in the original language and know the culture of the country, but we make sure that the funding allocation is gender- balanced as far as possible and that it supports writers from countries that aren’t often translated. All other things being equal, we try to privilege those books that need more exposure. So that programme has been instrumental in bringing writers into translation that might not otherwise have made it.

And the latest awards have had a really healthy representation of women writers; was that a conscious choice?

Yes, because when we narrow the books down for the longlist, we’ll then look at the language balance and the gender balance, and we try to make it as diverse as possible. I feel quite optimistic about where literary translation is at the moment compared to it was even a decade ago. Translators have created networks and are very supportive of one another; we’re not working on our own. There’s a lot going on and we’re all on the same page. Translated literature has outsold English literature for the first time, and despite the gloom and doom and all the rest of it, I feel quite optimistic about translating literature and about women writers as well.