Yesterday Olga Tokarczuk was announced as the winner of the (delayed) 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature. I’m not going to linger on the reasons for awarding the 2018 and 2019 prizes together – or about why I’m only focusing on Tokarczuk and not the 2019 winner – you probably already know them. There are also issues surrounding diversity, with many people criticising the 2018 and 2019 awards for being euro-centric and white (despite Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel Prize in Literature committee, saying in the week before the announcement that “We had a more Eurocentric perspective on literature and now we are looking all over the world” – as if looking is enough, a gesture towards inclusivity before falling back into old habits). These criticisms are valid points, and it’s important to make them: we can’t champion women in translation without considering how other forms of bias intersect with gender bias. I can’t pretend I wouldn’t have liked the 2019 winner to have been… different (in so many ways). And I’ll come back to Olsson later, because he had some pretty inflammatory things to say about women too…

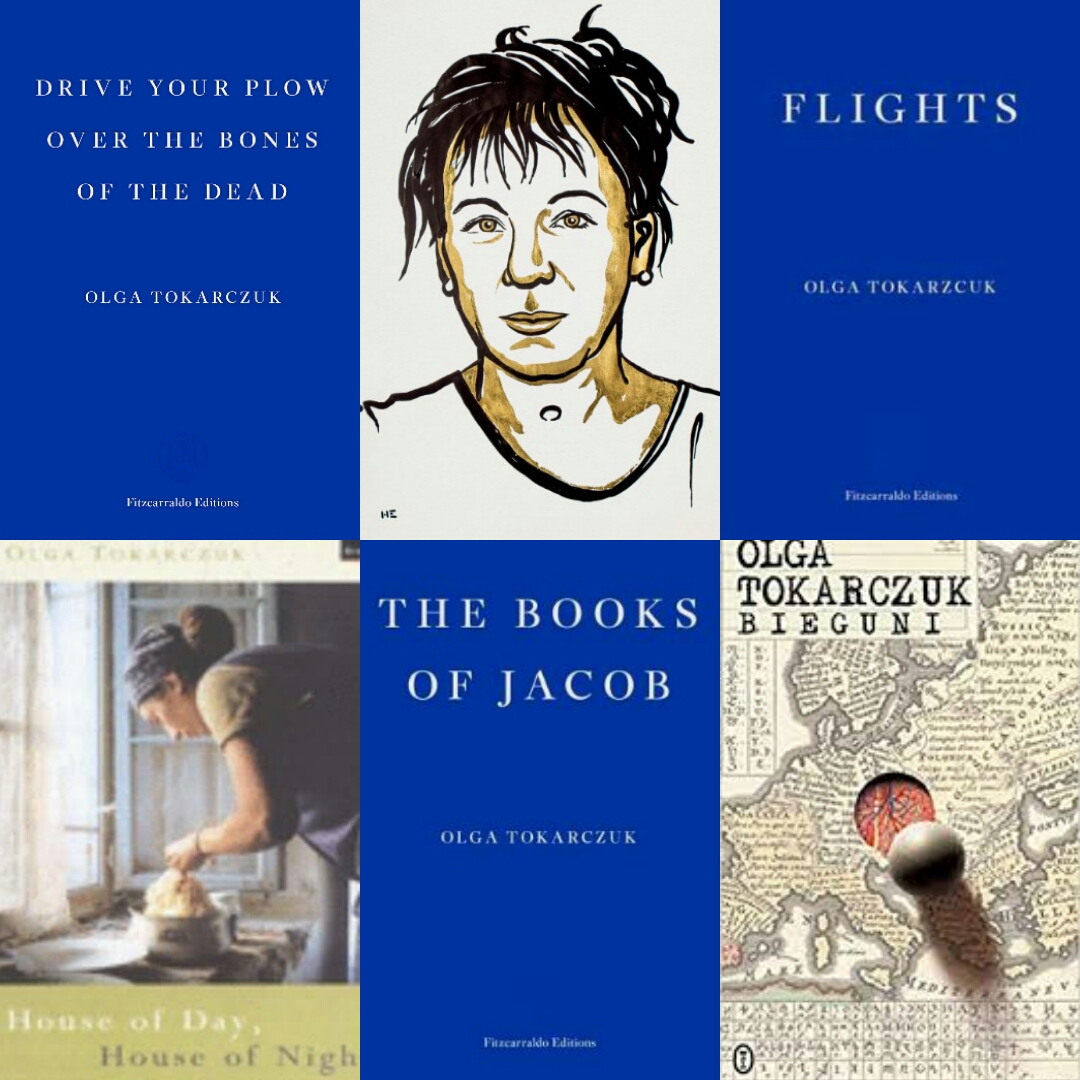

Regular readers will already know my admiration for Tokarczuk’s work – for the incandescent, challenging Flights (translated by Jennifer Croft) and for the gloriously fatalistic Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, and also longlisted this week for the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation). These were both published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, who form part of a wave of brave, outward-looking independent publishers resisting narratives of nationalism and isolationism, and who we need in these insular times. But though Tokarczuk may have exploded on the Anglophone literary scene with Man Booker International-winning Flights a couple of years ago, this was not an overnight success story. Rather, it was the result of years of work: Croft had been trying to get her translation of Flights published for ten years, and Lloyd-Jones, who translated Tokarczuk’s House of Day and House of Night back in 2002 (published by Granta Books), has championed Tokarczuk’s work (and Polish literature) tirelessly for years.

So yesterday’s win didn’t come out of nowhere. Tokarczuk has been widely read in Poland and in other European countries for decades. We’re the ones who are late to the party: it took fifteen years between the publication of Lloyd-Jones’s translation of House of Day and House of Night and Croft’s translation of Flights, which coincided with Poland being the guest of honour at London Book Fair, and the first time that Tokarczuk was tipped to win the Nobel prize. Then there was the Man Booker International win in 2018, and Fitzcarraldo’s nurturing of Tokarczuk’s œuvre (as well as the 2018 publication of Drive Your Plow, they will publish Croft’s translation of The Books of Jacob in 2021). I’m not suggesting that Tokarczuk won the prize because she was translated into English; that would reinforce the Anglophone dominance of the Nobel. But I do think that, for those of us celebrating the award in the English-speaking world, congratulations should also be extended to her brilliant translators, who have made her accessible to so many people who otherwise would not have been able to read her.

So there is much to celebrate. But there is also much still to do. Back in May, I was interviewed by a journalist who, when I mentioned some of the factors above, insisted that “Olga would have been published in English anyway” because she is a brilliant writer. I agree that she’s a brilliant writer – erudite, quick-witted, philosophical, and shrewd – but that isn’t the only reason her work is available for me to read. Indeed, attributing everything to a writer’s innate “brilliance” plays into the myth of meritocracy that so often excludes women and other marginalised groups from the top table. Chair of the Nobel Prize in Literature committee Anders Olsson also said in the lead-up to the announcement that “Previously it was much more male-oriented. Now we have so many female writers who are really great, so we hope the prize and the whole process of the prize has been intensified and is much broader in its scope.”

Wait, what? Now we have so many female writers who are really great? Ah, so THAT’s why only 14 of the previous 114 laureates were women. There just weren’t many women writers. Or not many great ones.

No. No. No.

They were there, they just weren’t seen. They were great, they just weren’t recognised. If we blindly and glibly accept that the gender disparity is about quality and not about visibility, then we are complicit in a system that privileges white Eurocentric masculinity. I’m delighted that Tokarczuk was awarded the 2018 prize, not just because of her brilliance, but also because of the way she resists borders, embraces diversity, and, in the words of the Nobel committee themselves, “represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life.” Note to the academy: Be More Olga.