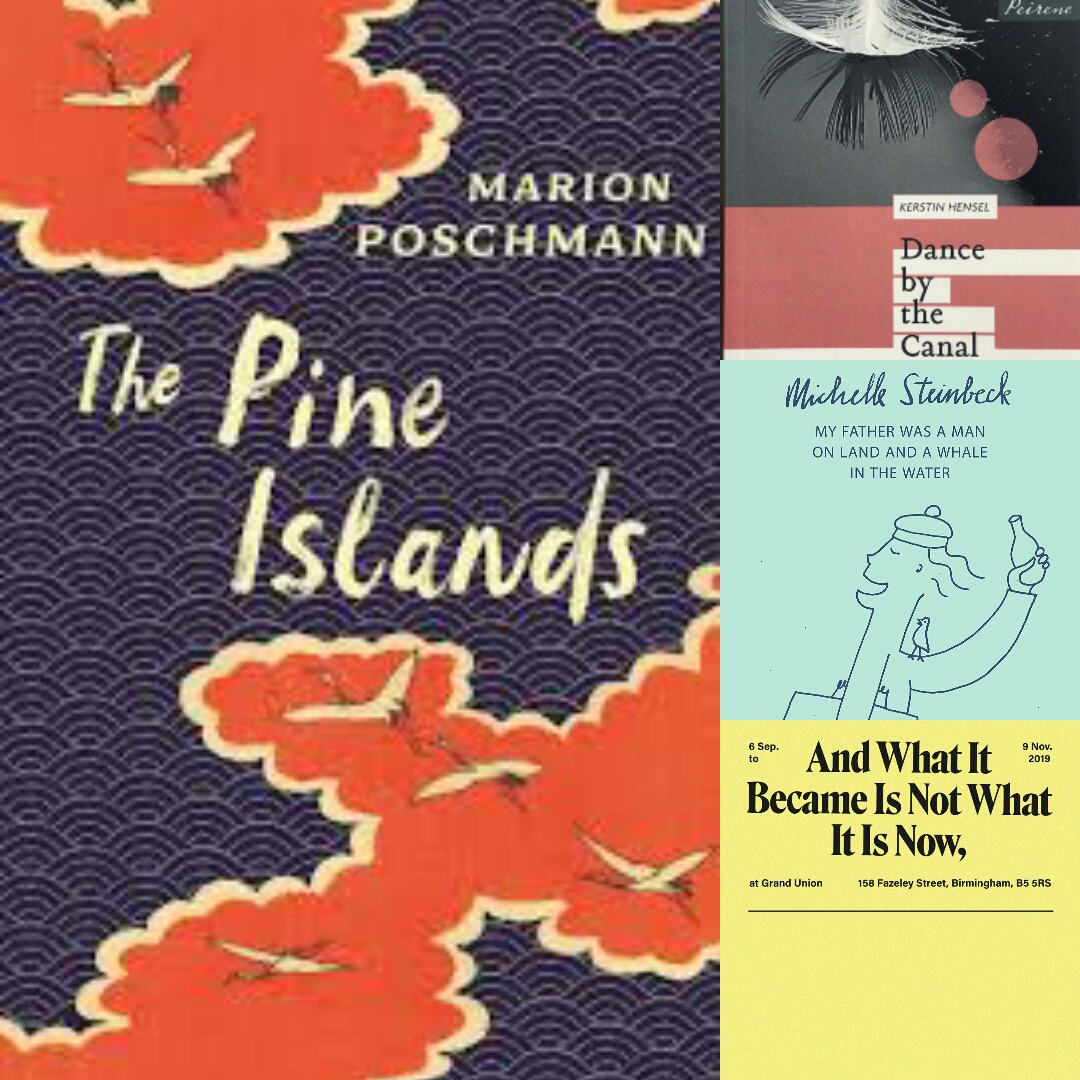

Jen Calleja is a translator from German to English, and a writer of fiction, creative non-fiction, and poetry. She was the inaugural Translator in Residence at the British Library (2017-2019), and in 2019 was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize for her translation of Marion Poschmann’s The Pine Islands (Serpent’s Tail, 2019).

How do you find new works to translate, and how do you choose publishers to pitch your translations to?

The majority of translations that I’ve worked on have come from direct commissions, with publishers getting in touch with me and asking me if I’d like to translate that book, or asking me to write a reader report first, then a sample. Pitching is an exhausting, long-game process, because publishers are very busy, and even if you find an amazing book you have to convince a publisher that it fits with their list. And translation is very expensive, so there’s the issue of whether a publisher would opt to do a translation if they weren’t looking to do one. I have pitched in the past, but I’ve been quite unsuccessful, and I think that’s something that quite a lot of even experienced translators share. It’s an arduous process and can be quite disheartening.

And how did you come across the work of Michelle Steinbeck and Marion Poschmann?

I used to work at the Goethe Institute, and I was involved with the New Books in German magazine. One of the editors there recommended Michelle’s book and it was everything I loved – a surreal contemporary fairytale, which is the kind of writing I really adore. I was reading Leonora Carrington at the time and it reminded me of her, and of Angela Carter, and I read it and mentioned to the Swiss Arts Council that I would love to translate that and they told me the rights were available. They had been sold to Darf Publishing, and so I put all my energy into convincing them that I should be the one to do it, so I did a sample and I contacted them with that, and they commissioned me to do it. As for Marion, I’d heard of her when Serpent’s Tail asked me to do a reader’s report, and I read it (The Pine Islands) and recognised that it was very special and unusual and unexpected. Obviously I didn’t realise it would end up shortlisted for the Man Booker International prize, but I was very confident that it was amazing.

How has being part of the Man Booker International prize helped to promote your work as a translator, and do you feel that the importance of translators is represented in media coverage of the prize?

It gave me validation as a translator to be nominated for a prize like that, because so many of my heroes have been up for that prize. But it also made me feel very panicky because of coming under such scrutiny; many of us witnessed the level of attention Deborah [Smith] had with The Vegetarian, I was very aware that it brings a lot of focus to your work in both good and bad ways. In terms of the media reception, a big deal was made about the fact that it was “dominated” by women, which made me feel very strange because I thought it was presumptuous and it made me feel uncomfortable. I was approached by the New York Times about a piece on why there were so many women translators on the shortlist, and I said that I thought the whole question was ridiculous, that this isn’t something that women are biologically better at, and if it had been the converse no-one would have bothered discussing it. So that was really reducing something that should have been very celebratory for the books, when so much space was taken up by the fact that we were women. There was that moment as well when The Guardian were reporting on the prize and forgot to mention any of the translators in the print edition and had to correct it online. So that missed the whole point of the prize. And you get people saying “I don’t understand why translators get half the money”. But the winner always gets a huge amount of publicity, which is amazing. And the way the build-up to the prize works is to get as much attention as possible for the books at the longlisting and shortlisting stage.

What do you perceive as the greatest challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature, and how does this affect who gets published and who gets translated?

Speaking from my own experience, there are a lot of different reasons why it happens. In terms of German-language publishers commissioning sample translations, nine times out of ten the authors they choose will be male. I’ve done about twenty sample translations in the past few years, and nearly all of them have been men. Also English-language publishers are interested to know if an author has already been translated and won awards, and certainly in Germany it’s often commented on that the longlists and shortlists for awards are predominantly male. So there are issues in the whole infrastructure, and then in the publishing industry there’s still not parity for women being published in English, let alone in translation. And in reviewing culture we know that women aren’t reviewed as much as men, so the problem is from the top to the bottom. There are obviously other issues, such as class: other translators have commented that if you translated a woman, because of the class structures in other countries you’re translating women who are predominantly upper or middle class, so they get translated, but what about all the working-class authors? I think about this a lot, because I’m from a working-class background. Michelle is from a working-class background, but usually you’re translating authors from a completely different background to you, one of privilege. But the gender question is one I’m very aware of. I only really see women if I’m trying to seek out something new.

What do you think might usefully be done to respond to and overcome such biases?

It’s not just in the publishing industry. Sexism and gender bias exist in society as a whole, so until we’ve reached full equality in all realms of life… I mean, people are still challenging the idea that there is gender bias in literature, and there is the VIDA count which is trying to concretise those figures in terms of bias, but people are still against it. So firstly there has to be an acceptance that it exists. There are people consciously opting into publishing women; for example with Marion Poschmann, the publisher specifically wanted to publish more women in translation. So people are making those kind of changes, but it has to be a long-term thing: it might be that for the next year or two people make a big thing of publishing women to push it forward, but people are so reactionary against that kind of positive discrimination without really acknowledging what comes before it. It doesn’t happen in a vacuum, it happens in a historical context. So it’s about making some real choices about women in translation, making an effort to work with women translators, using that as a consultancy basis to find more women. Maybe not using awards as a basis for quality all the time. If the problem already exists in the original country and setting in terms of awards, then a lot of women will struggle.

Do you think that German-language women writers are well represented in translated literature? What/ who would you like to see gain greater recognition?

German as a language is very well represented, better than some other languages. Most of the major European languages are doing okay. There are some amazing German-language women authors, for example Jenny Erpenbeck is one of the major stars of the last few years, and there are many authors who I’ve met for example at the Austrian Cultural Forum who I’d love to translate, but like any foreign-language author who hasn’t been translated, so many of them are famous in their own country but have no recognition here. For example, Olga Tokarczuk was renowned in her own culture, but it’s only in the last couple of years through translation that she’s gained recognition over here. People are saying that one day she could win the Nobel Prize, but without translation that wouldn’t happen [note: since the date of this interview, Tokarczuk did indeed win the Nobel Prize in Literature]. And that’s because English has such a dominant hold on literature worldwide, which is wrong. And that’s why we push for translation into English, because we need it. I mean that in an existential, soul sense; we’re starving for outside voices. We’re so insular and becoming more insular, we think that our way of looking at ourselves is enough, but the only way to really know yourself is to ask a stranger or someone who can see us from the outside, but we don’t want that. There’s a kind of arrogance there, and it’s the reputation that we’ve always had and it’s getting worse and worse, and now we’ve started to believe our own myth, and that’s why it’s important to have translation.