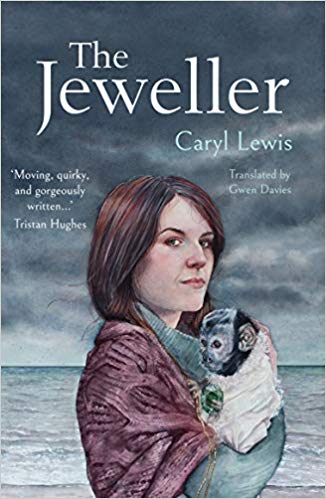

Translated from Welsh by Gwen Davies, Honno Press (2019)

When I received The Jeweller, I was shocked to realise it’s the first book I’ve ever read translated from Welsh. I’ve read books by Welsh authors written in English (most recently, the wonderful Pigeon by Alys Conran, published by Parthian Books), but never anything originally written in Welsh. So this was a first for me – but what a first. If, like me, you’ve never read a book translated from Welsh before, I can only urge you to start with this one. Published by Welsh women’s press Honno, this is a haunting story of death, bonds, the objects we carry with us and those we leave behind. It features a cast of believable, perfectly observed characters, a dexterous plotline with multiple sub-plots and several twists, and is written in a gorgeous near-Gothic prose.

“That was the horror of love: your sweetheart could stick a knife into your eyeball and sharpen it a notch every chance they got.”

Mari is the jeweller of the title: she has a stall in the market of a small coastal town where she sells second-hand jewellery, pieces bought at auction or finding their way to her by other means, and which “after years of being longed for, loved and flaunted by other owners, … shared Mari’s company for a while before finding a new home.” The jewels are not just cast-off trinkets, but have a life of their own as they pass from one owner to the next; similarly, Mari is not simply an eccentric hawker, but has a secret hidden away in “the shroud of a sheet that kept it clear of cold and dust”: little by little, in the privacy of her home, Mari is working on an uncut emerald, “a chip of grave-cloth green” with which she feels an intimate connection, and which offers a superb subtext. At the heart of the emerald is a unique feature that could be the key to its brilliance, but the work needed to bring it to the surface must be carried out delicately and expertly: one false move and it could shatter and be irreparably ruined. This is a subtle metaphor for Mari’s own life, which is revealed to us little by little in the course of the narrative, layers of brittle carapace slowly chipped away until the aching heart is exposed. It could, however, also stand as a metaphor for the book itself, which manages to be both tense and languorous, its sudden bursts of raw beauty mirroring Mari’s intermittent urges to work furiously on the emerald, and its drawing back at the moments of greatest drama echoing the way in which Mari wraps up the emerald and hides it away, leaving it to throb gently just at the edges of her awareness. The writing in the translation is superb: like Mari’s handling of the emerald, aware that “nothing should obscure the light’s journey through the gemstone”, Davies allows nothing to obscure the opalescent beauty of Lewis’s prose:

“But we shouldn’t be afraid of beauty, should we?

Since possessing the stone, Mari had struggled to admire it without wanting to cut it. To open in it just the smallest window. But yes, of course such gorgeous gems can trick you. She’d heard of jewellers sent insane by knowing a stone’s face as incisively as they did their own. They’d put all their faith in it. Been led to believe they had the key to every cell. That it was rock solid. But they’d take up their tools and it would flake to powder just the same. Leaving the memory of that germ of beauty.”

Mari is a private, taciturn character, and it is a feat of both Lewis’s storytelling and Davies’s translation that we are allowed such intimacy with her. We learn of the strained relationship with her father, the local reverend, full of divine love for others but brutal to Mari: “He had been her life. He’d tried diverting her ardour to loftier heroes. But an ordinary father’s love would have been enough. He’d been kind to so many people, impatient with others, even cruel to a few. He was only a man, after all.” The confidence and compassion to which we are invited is aided by the excellent supporting cast, whose relationship to Mari crystallises slowly as the story progresses. We meet her fellow market workers, and follow their routines and relationships as this small community faces the closure of the market, their slow life overtaken by industrialisation. As well as the human characters, we also encounter Mari’s pet monkey, Nanw, who lives in a cage in Mari’s bedroom but whose backstory is unclear. The only part of the narrative that I was strangely unmoved by, though, was a key moment between Mari and Nanw in the roiling sea that had been lapping at the edges of the story throughout; I struggled to get beyond a fairly basic interpretation of Nanw as a surrogate family member, and would be interested to know how others have read this relationship.

As well as her stall at the market, Mari intermittently earns money helping her friend Mo to clear out the houses of people who have died with no next of kin to take care of their belongings. From each house Mari rescues a photograph which she frames and displays on her mantelpiece, rescuing from loneliness and obscurity people she never encountered in life, and surrounding herself with the lives of the dead. This is no quirky macabre obsession: Mari is searching for something, and when the revelation of what this was came, I was completely blindsided: it was a stroke of brilliance, and of wonderful storytelling. Often the phrase “it took my breath away” is an overstatement, but not in this case. You’ll know by now that I don’t do spoilers, so no more on that – but I highly recommend that you read and experience it for yourself.

Review copy of The Jeweller provided by Honno Press