Translated from Indonesian by Stephen J. Epstein (Harvill Secker, 2020).

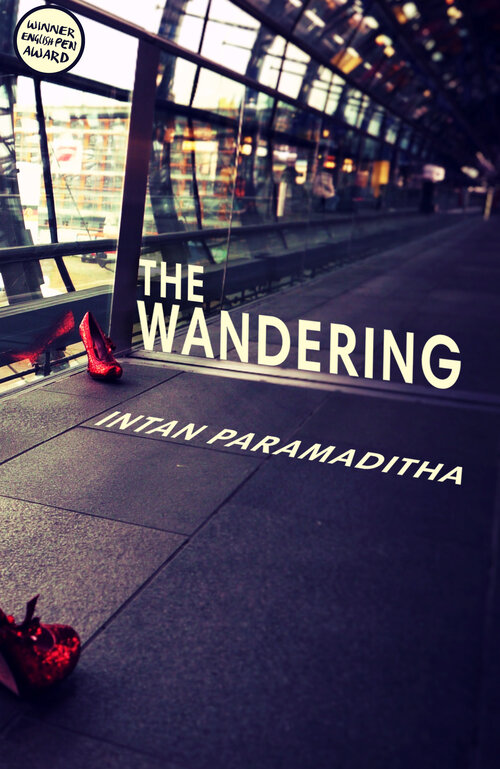

The Wandering is an innovative, thought-provoking twist on the Choose Your Own Adventure genre. Written in a compelling second-person narrative, it is based on the following premise: You are bored with your predictable life in Jakarta, and you wish to escape. A demon lover comes to tempt you with a gift that could be cursed: a pair of red shoes that will take you wherever you want to go. But be careful what you wish for, because you may not like where you end up – and you will never be able to return home. What do you do?

This is the perfect match of theme and genre, and is impeccably executed. With every choice I made I was curious about the alternative, where it would lead and whether I’d end up with the same destiny, whether the ending is the same whichever path you take (it’s not), and whether you experience the whole book but in a different order (you don’t). I loved Choose Your Own Adventure books when I was a child, but I never had much luck with them. I’d usually end up sacrificed on a jungle altar by page 20 (and it seemed every path led back there), so I really wanted to be a survivor in The Wandering. In for a penny, in for a pound, I thought: in this magical literary world where I’ve made a pact with a devil for a pair of red shoes, I tried to make the choices I really would make, or at least would make in a dream, since the reality is fairly unlikely to come to pass – so yes, go on, let me always move forwards instead of playing it safe, give me a magic mirror that allows me to see my true self, bring it on!

I met a sticky end before I was halfway through the book.

I went back to the last big choice: the magic mirror. Maybe I should have gone back further, to a previous choice: in my second adventure I had a banal but steady life, I was even something like happy. But what if I hadn’t settled down with the handsome yet uninspiring illegal immigrant? I went back to that choice and tried again. Another mundane relationship, another settled existence with neither great drama nor great happiness. So my first choice about the mirror wasn’t the problem, but this must mean that somewhere earlier on I made a false step.

You’ll notice I’m talking about my character in the first person. This is one of Paramaditha’s great achievements: making me believe in the story, become invested in it, wanting to know all my possible fates in this crystal ball of a novel. Part of this is down to her second person narrative: addressing her readers as “you” is designed to create an intimacy that I found entirely successful. Part of its triumph lies in the constant suspense, which is excellent – I suspect that a cynic might occasionally find it a little melodramatic, but I threw myself into it (I mean, if I’m going to have a pair of magic red shoes gifted to me by a Mephistophelian lover, then I’ve got to expect a little melodrama) and so it didn’t bother me at all. In fact, there is only one sentence that I found slightly heavy-handed, when we are told that “you sense that your decision will determine your path from here.” This is one of several conscious references to the genre (“You began to suspect that your failure to transcend mediocrity stemmed from a wrong turn in your life”; “Adventures don’t always offer unlimited choice”; “If you’re having an adventure you always want to know what would have happened if you chose a different road”; “Did you make the wrong choice?”), but in over 400 pages was the only one that felt a little forced to me.

As for the translation, it is both playful and dramatic, acrobatic without ever losing clarity. Reading the author’s acknowledgements and the translator’s note, I learnt how closely Epstein collaborated with Paramaditha, and the editing debt he acknowledges to Paramaditha’s friend and champion, author and translator Tiffany Tsao. It’s clear how closely and passionately they have all engaged with this work: Epstein makes stunning choices of verbal adjectives (“You felt as if your limbs were lashed to the bed”; “the lanes clogged with traffic”), offers pithy renderings of epigrammatic philosophical observations (“as befits a journey, happiness is a terminal, not a destination; nobody stays there too long”) and perfectly captures the darkly mischievous voice that directs, admonishes and tempts: “Forgive the imperiousness of this adventure, but you know that sometimes life takes away all options. Choice is a luxury. Marrying Bob is your emergency exit” (forgive the spoiler; marrying Bob is only one of a great number of options!); “If you want to know the fate of the red shoes, turn to the next page. If you don’t want to know the fate of the red shoes, well, who gives a damn? Turn to the next page”; “If you want a final adventure that might only create a spectacular mess, turn to page 405” (and yes, OF COURSE I turned to page 405). I’m curious to know how Epstein translated – whether he followed a thread through to its conclusion and went on the journey too, or whether he did it in a more linear fashion, jumping between stories while advancing chronologically through the pages. I can’t help but hope that he went on the wandering as he translated.

This book is escapism taken to the next level, while still making serious and significant comments about modern societies. Intertexts range from well-known literary works, popular songs and films to more subtle (and, I’m ashamed to say, over my head) references to Indonesian literature which, when they were pointed out to me, made me feel very acutely the question posed by one of the characters: “why don’t we hear of Indonesian writers outside the country?” Alongside such mirrors (magic or otherwise) held up to her adventurers, Paramaditha also excels at mordant observations about migration, the brutality of Trump’s America, the falsehood of the American dream, and the personal dimension of the “refugee crisis”, and many of the stories reprise the refrain, also discussed in the afterword, “good girls go to heaven, bad girls go wandering”. As befits the theme and genre, reflections on movement versus stasis abound (“For some, the world is indeed very small. But a small world such as this is not – or hasn’t been – yours. So far, the world you know is vast and random”), but above all, The Wandering is about relationships – their integrity, their contingency, their familiarity and their failures. As I was turning though pages to get to my next instalment, I would see names that were unfamiliar, and know that another choice meant different encounters: this made me think about the world, about chance and fate and the choices we make: some of these are just detours, different ways of ending up at the same place. But others change our direction, leading to different encounters, places, and life paths. When you’ve read enough of the possible stories you realise you don’t always meet Meena, or Yvette – it is your choices that bring you to them or let them pass you by. You might end up in the same place – even on the same flight to Peru – but with an entirely different life, observing the people who would have been close to you if you’d made a different choice.

I *think* I had every possible adventure in the end. Some of them were against my instincts and turned out satisfactorily. Some were instinctive and pretty ill-fated. If I learned anything about myself, it’s that I’m better at decisions in real life than in a dramatic alternative universe where I’ve made a pact with the devil for a pair of magic shoes. And what about you? I recommend that you don these glorious red shoes and see where they take you…

Review copy of The Wandering provided by Harvill Secker.

Follow the “Red Shoe Odyssey” on Intan Paramaditha’s website, and view the shoes’ adventures.