Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Helen Vassallo

8 March 2020This year’s theme for International Women’s Day, “Each for Equal”, ties in with the emphasis on intersectionality that is key to any kind of progressive feminism. Since “intersectional feminism” is itself a term that can be bandied around to encompass everything and nothing, I’ve been focusing my thoughts on what it can mean for women in translation.

I recently wanted to avoid over-using the word “empower” in a piece I was writing, so looked in a thesaurus and was surprised to find “privilege” offered as a synonym. Perhaps my surprise is partly prompted by the ubiquitous – and scathing – appearance of the term “privilege” in reaction to Jeanine Cummins’s controversial novel American Dirt, but it made me wonder: why is “empower” a positive word and “privilege” so loaded with scorn? Can the two be reconciled? Empowerment as an active process can be the sharing of privilege, or rather, using what privilege we have to work towards equality and justice for those who do not have that privilege. The criticisms levelled at Cummins were for appropriating Mexican experience, speaking for (or over) Mexicans, rather than giving them the platform to speak for themselves. It is the use of privilege that makes it not entirely synonymous with “empowerment”: privilege can be used to empower, but it can also be used to perpetuate established systems of power, and that’s where change needs to happen.

In 1981, writer and activist Audre Lorde stated that “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” This is as true today as it was thirty years ago: how can we claim progress in the movement for gender equality in translated literature if predominantly white European women are getting translated? And how many of those are straight, cis, middle-class, non-disabled? Let me be clear: this is not an indictment of being any of those things. The problem is when we see these characteristics so frequently that they come to be synonymous with “normal”, and we forget that there are other voices that we are not hearing. In her powerful manifesto We Should All Be Feminists, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie affirms that “culture does not make people. People make culture. If it is true that the full humanity of women is not our culture, then we can and must make it our culture.” The full humanity of women does not mean only one model of womanhood that we define as “normal” – and if we can’t change culture overnight, we can at least make conscious changes about the way it is represented on our bookshelves. If we care about equality, then we have a responsibility to read books that are not just about our own experience, that do not simply confirm our own way of living in the world. It is a source of constant bewilderment and frustration to me when reviewers or readers claim they couldn’t “relate” to a book because they don’t know the culture. I find this the literary equivalent of going to a different country and heading straight for the English pub: why should writers from other cultures make their narratives more westernised just to make them more easily digestible to us? And doesn’t the translator have a responsibility NOT to impose that in the translation? One of my favourite books, Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season (translated by Sophie Hughes for Fitzcarraldo Editions and reviewed here), was recently described by Ann Morgan as a book that does not “come meekly to the reader”, and this epitomises everything that I think translated literature should be: a door opened onto other cultures, a wake-up call lest we slip into complacency, a reminder that identity is never singular and that diversity characterises our planet.

In the Building Bridges interview series I conducted last year, almost all of my brilliant interviewees talked about the barriers women writers face at every stage – before they write, then when they seek publication, and after that to be brought to the attention of English-speaking literary agents. So there are two major intersecting prejudices here: being a woman and being “foreign.” With regard to how literature from outside the Anglosphere makes its way in, Tiffany Tsao recently gave an illuminating and impassioned perspective on the way in which national cultures are “packaged”: who gets to choose how their culture is represented in literature? Not the women, I’ll wager. And certainly not the full humanity of women. Then Margaret Carson identifies the issue of visibility for women writers in both their home culture and in translation even when they are published (in an article from In Other Words that you can read by searching the archives on the women in translation tumblr). Next, recent research by Richard Mansell confirms that even if they make it into translation, women are less likely to be longlisted for big literary prizes. These barriers are amplified for women of colour, working class women, disabled women, trans, queer or non-binary writers, but we CAN help to dismantle them. Mansell notes that “change is happening right now in translated fiction,” indicating that we have an opportunity, a moment to be seized before it passes: market logic suggests that if the demand is there, slowly the supply will follow – and that’s the first link in the chain of barriers that I mention above. So, in the spirit of “Each for Equal”, let’s seek out these voices, and support the publishers who champion them. If you have the privilege/empowerment potential of disposable income, support by buying books. If you don’t, borrow and request from your local library. The more these books appear on shelves, the more “normal” it will be for them to exist there.

*****

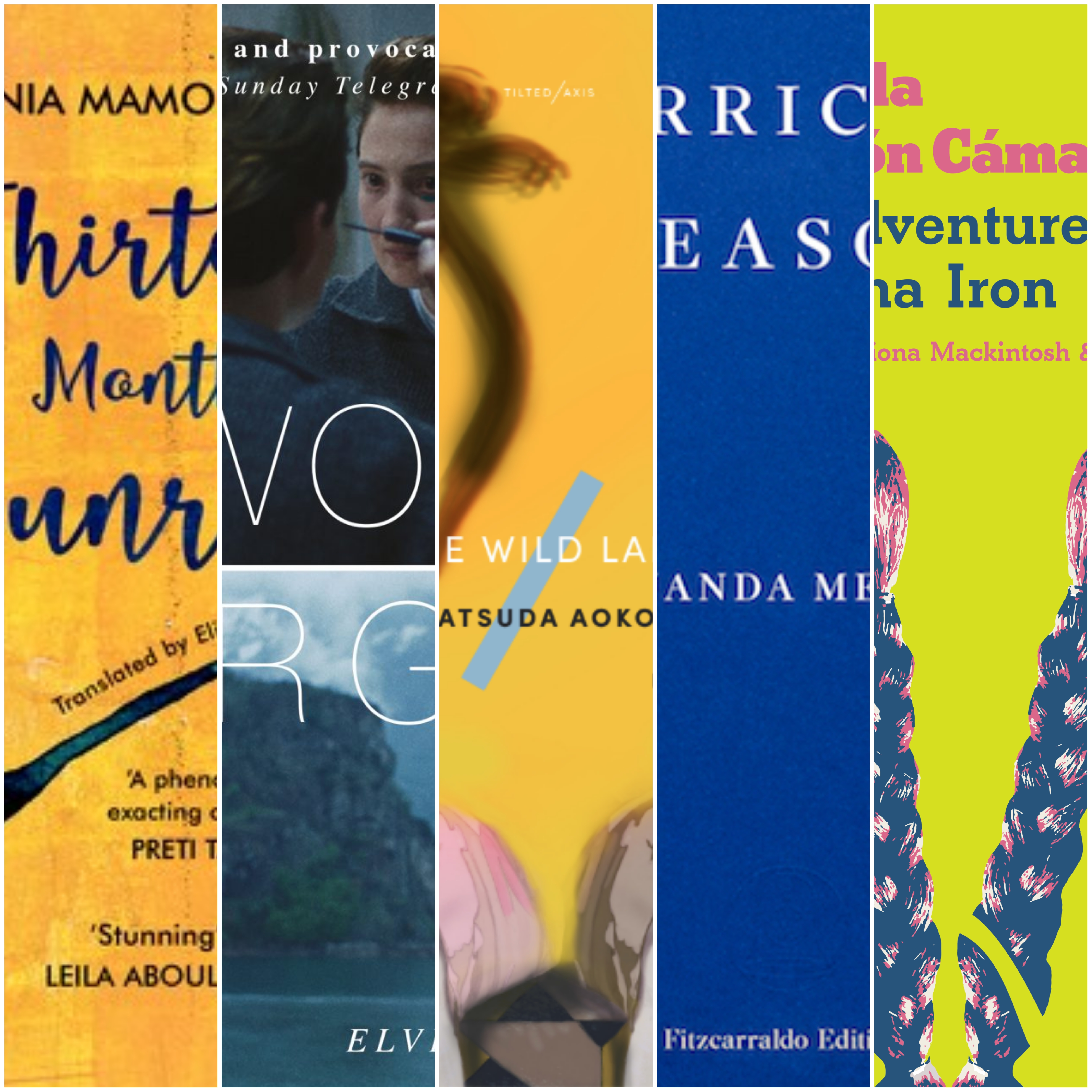

Here are a few recommendations of voices and stories that challenge preconceived ideas of “normal” in its various forms, with links to the publishers’ websites:

Elvira Dones, Sworn Virgin, translated by Clarissa Botsford. A rare literary insight into Albania’s landscape and traditions, this brave, absorbing and deeply moving tale of a woman sworn to live as a man reflects on selfhood, sacrifice, and what “being a woman” means. Published by And Other Stories, the only press to commit to Kamila Shamsie’s call to make 2018 a Year of Publishing Women.

Matsuda Aoko, Where the Wild Ladies Are, translated by Polly Barton. This collection of contemporary feminist twists on Japanese ghost stories puts women at the centre, allowing them to unleash their power through a web of spooky, wry and interconnected tales. Published by Tilted Axis Press, champions of intersectional reading who are on a mission to decolonise translation by “tilting the axis of world literature from the centre to the margins.” Tilted Axis have also published Indonesian writer and disability activist Khairani Barokka’s Indigenous Species, a sight-impaired-accessible art book (though, for clarity, not a translation).

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, The Adventures of China Iron, translated by Fiona MacKintosh and Iona MacIntyre. This queer feminist re-telling of a gaucho epic is a bold, revolutionary and subversive dialogue with Argentina’s history and literary canon, and is currently longlisted for the 2020 International Booker Prize. Published by Charco Press, whose catalogue to date includes 17 titles from diverse voices from across Latin America; 8 of the 17 are by women (and with the next release, it will be a perfectly balanced 9 of 18!)

Fernanda Melchor, Hurricane Season, translated by Sophie Hughes. A torrential vision of people on the margins of society, and a rage against a world that abandons there. Set in the fictional Mexican town of La Matosa, a place riven with violence and superstition, this is a tale of the monsters we make with global indifference, and is currently longlisted for the 2020 International Booker Prize. Published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, who deliberately sought out a Polish author in response to the backlash against the Polish community in the UK following the Brexit referendum. You might have heard of that author, Olga Tokarczuk, since then…

Rania Mamoun, Thirteen Months of Sunrise, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette. The first major translation of a Sudanese woman writer, this anthology brings together urgent, thoughtful and occasionally surreal short stories that reflect variously on love, contingency, broken promises, despair, religion and corruption. Published by Comma Press, who are known for their radical approach to publishing and have just released the groundbreaking anthology Europa28, bringing together women’s voices from across Europe in the wake of Brexit.

For a great list of intersectional feminist readings originally written in English, see this guide that Sophie Baggott compiled for the International Women’s Development Agency.