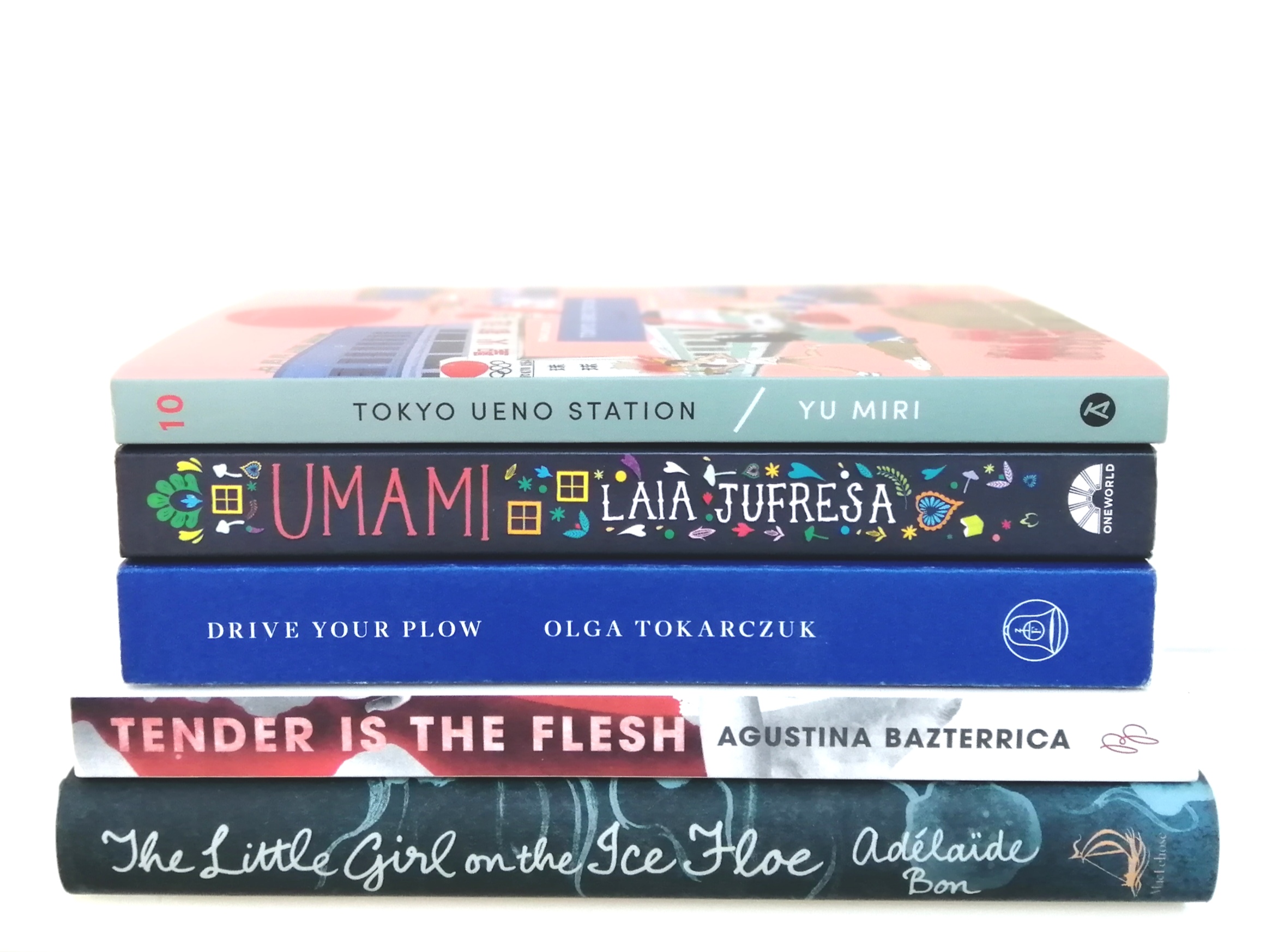

In my recent open letter, I talked about my belief that literature from other cultures – especially from marginalised voices – can be a crucial means of fostering empathy in times of crisis. As I watch news coverage of the coronavirus pandemic I become ever more convinced of this, and so here are five books by women in translation that I’m recommending for the global crisis.

1. Was anyone else less than sympathetic to Mike Pence’s complaint that the coronavirus nasal swab test is “invasive”? For those who feel conflicted about a potentially life-saving rapid sweep of the nostril with a cotton bud, I recommend:

The Little Girl on the Ice Floe

Adélaïde Bon, translated from French by Ruth Diver, Maclehose Press (available in the US in Tina Kover’s translation for Europa Editions).

This account of living with the trauma of child sex abuse is as urgent as it is painful. In 1980s Paris, Adélaïde Bon was a happy, privileged nine-year-old living a charmed childhood, until the day that a stranger raped her in the stairwell of her building. In this brave and powerful memoir, Bon pieces together the incident that shaped her life, in an attempt to come to terms with its devastating consequences. In her determination to reconstruct the events and so reassemble herself, Bon confronts the man who defined her life by taking her childhood. A brief nasal swab won’t seem quite so melodramatic when you read what it is to keep living after every intimate orifice has been penetrated by a paedophile.

*

2. I’ve seen some scaremongering (and, as far as I can tell, unsubstantiated) clickbait speculating about fatal disruption to the food chain: before propagating sensationalist news, want to know how bad that really could be? I recommend:

Tender is the Flesh

Agustina Bazterrica, translated from Spanish (Argentina) by Sarah Moses, Pushkin Press.

This chilling, gripping study of the cruelty humans are capable of inflicting on each other by artlessly following those who peddle lies and trade in fear is the ultimate dystopian novel: this is a world in which it is legal to breed and slaughter humans whose vocal chords have been cut so that you won’t have the inconvenience of hearing them cry out in pain as they are dismembered for your dinner party. The most terrifying thing about this superb debut novel is how believable Bazterrica makes the circumstances: it really doesn’t feel like a massive leap from the discovery of a deadly virus that led to the extermination of all animals and paralysis of the food chain, to the legalisation and normalisation of eating human flesh. After you read this, finding alternatives to pasta/ eggs/ flour won’t seem like much of a hardship (and a plant-based diet will never have seemed so appealing).

*

3. Described in various (sometimes dubious) contexts as a “great leveller”, this virus hits us all and doesn’t differentiate. It will attack Hollywood stars, world leaders and heirs to thrones indiscriminately, but make no mistake about it: some social groups will suffer from it more than others. To help us remember our common humanity, I recommend:

Tokyo Ueno Station

Yu Miri, translated from Japanese by Morgan Giles, Tilted Axis Press.

The radical divide between the very wealthy and the very poor is shown in this lyrical meditation on loss and home as a homeless man dies in Tokyo’s largest park and finds himself condemned to haunt the park indefinitely in his afterlife. Tokyo Ueno Station is a sharply observed and extraordinarily beautiful novel about the fate of those on the edge of society: a man who has lost everything watches the living carry on making their mistakes, unable to warn or help those he once knew and loved. His story is intertwined with that of the Japanese Imperial family: in his life, he was sporadically relocated during imperial visits so that his very existence would not be an eyesore to those who needed to believe in the prosperity of their nation. A magical and poetic novel, which reminds us to be kind to the people who are most vulnerable, and to be the community we want to see.

*

4. Much of the supposedly “reassuring” narrative around coronavirus deaths rests on the majority of fatalities being people who are over 60, or who suffer “underlying health conditions”. Though I know this is meant to offer relief that the majority of those affected will recover, a death is a death – a personal, irreconcilable loss – no matter what the age or state of health of the deceased. As a reminder that the life of an older person is worth no less, I recommend:

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead

Olga Tokarczuk, translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd Jones, Fitzcarraldo Editions.

This tale of vengeance, murder, and retribution is also a powerful reflection on ageing and perceptions of “usefulness”. Through her inimitable narrator, Mrs Duszejko, Tokarczuk offers profound insights into the human condition, the isolation of the non-conformist, the lack of equality for women, and the daily impatience faced by the elderly. Drive Your Plow is also an indictment of animal cruelty, and a reminder not to stand in judgement or to dismiss those who are different from ourselves. By turns hilarious and profound, Drive Your Plow is a book that can be read and enjoyed at any time, but which has particular resonance right now with its philosophical reflections on life and death, acute observations of ageing and invisibility, and poignant reminders about the luxury of being able to cross borders.

*

5. One thing I’ve loved seeing in the media is stories of people who have never before interacted with their neighbours now providing them with a lifeline, and streets coming together for socially distanced exercise or dance, or to applaud frontline healthcare workers. For anyone who’s never talked to their neighbours before, I recommend:

Umami

Laia Jufresa, translated from Spanish (Mexico) by Sophie Hughes, Oneworld Publications.

This beautiful, polyvocal novel is set in and around Mexico City, and tells the story of a group of people living in the five houses of Belldrop Mews, during a particular period of their communal lives when “the dead weigh more than the living.” The story/ies are narrated from five different perspectives, but each character in Umami is quietly struggling with grief and loss, and trying to reassemble a broken life. They interact, though not constantly, and when they do, their common grief is never far from the surface. Yet they hide this, trying to maintain an appearance of normality and of coping – but if we can learn one lesson from this global crisis, it is that we are not alone in our fear and frustration, and that solidarity and community will help us to overcome the dark times.