Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Helen Vassallo

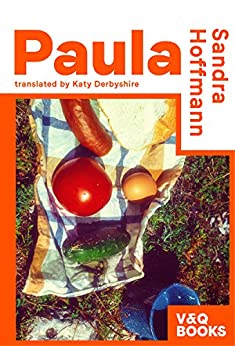

16 September 2020This week sees the launch of German publisher V&Q’s English-language imprint: spearheaded by Katy Derbyshire, the new imprint brings some of the most exciting new fiction in German into English. Two of the three launch releases are by women writers, and so this is the first in a two-part V&Q bonanza: today I’m reviewing Paula by Sandra Hoffman, translated by Derbyshire herself, and next week I’ll be talking about Daughters by Lucy Fricke, translated by Sinéad Crowe.

Paula is Hoffmann’s attempt to understand a woman who was stiflingly close to her but yet remained distant. Her maternal grandmother (the eponymous Paula) is a troubled and taciturn woman who has never revealed the identity of her child’s father: a devout Swabian Catholic, Paula is typically depicted with one hand in her apron pocket, worrying her rosary beads as she works her way through the prayers that are the silent soundtrack to her granddaughter’s life and narrative. Imprisoned in a silence that takes over the house and leaves her adrift into adulthood, Hoffman sets out to reclaim words never said, and so to understand Paula, “as though all the unspoken words were seeking ways out of that mute body and into the room, forging the way to you.” She is clear from the start that her imagination will fill in the blanks of a story she only knows in fragments (“I am an unreliable narrator”, she warns us and, later, “memory is inconstant”). As well as words, Hoffmann considers the importance of photographs in reconstructing memory (or in constructing it where it is withheld). Static images of a moment fixed in time allow the person viewing the photograph to impose a story on them, but in the end they too are wordless and can never create a story beyond the moment that they capture. Fiction, then, becomes Hoffmann’s only recourse to “close gaps between image and image, fragment and fragment.”

I appreciated the truthfulness of the blanks and gaps, for there is no plausible way that Hoffmann could offer a full backstory of someone who, as she acknowledges, “took her whole life to the grave”. Yet this all-pervasive silence is harmful, persisting doggedly even when the young Hoffmann was taken to family therapy because of the eating disorder that the deliberate silence passed down through generations has triggered. Hoffmann’s narrative is prompted by her need to know who her grandfather was, to break through the schweigen (a word I’m delighted to have discovered – it opens the text and features in the excellent translator’s note), but this is impossible as Paula died without revealing her secret, and left no posthumous clue. We only know fragments – for example, that Paula was engaged to a man who died in the war (but could not have been the father of her child), or that she drowned her sorrows in plum brandy when Hoffmann’s mother was young – but we never get to know Paula beyond the melancholy of a life half-lived, and which is perhaps best summed up in this reflection: “It was as though her laughter forbade itself, as if taking joy from life was forbidden, as if she had sinned so severely against her God that only prayer helped now.”

Paula has devoted her life to prayer, and this religious devotion is passed down to her granddaughter in the form of guilt and shame: as a child, Hoffmann becomes obsessed with saying five flawless “Our Fathers” to cancel out any involuntary negative thoughts she may have had about her grandmother, convinced that otherwise something bad will happen because of the bad thoughts. In this sense, Paula functions as a kind of malevolent deity, who her granddaughter believes is all-seeing and all-knowing: Paula is a difficult presence, suffocating and invasive in her silence, and fostering Hoffmann’s fear that “she’ll make me turn into her, she’ll make sure there’s no difference between her fear and mine, between her prayers and mine.” As secrets and silence swell around her, the young Hoffmann feels that there is no room in the house for her, and envies friends who have a space of their own with no grandparent constantly lurking outside their bedroom door. Ultimately, then, she creates her own “territory” by writing: writing is not only an attempt to understand her grandmother, but also to free herself from Paula, to understand the difficult closeness of their relationship and to come to terms with it.

The translation is, unsurprisingly, excellent. Derbyshire is a skilled linguist, sensitive to the nuances between her two languages and attuned to questions of register, syntax and lexical variety. Some of my favourite instances of word choices include verbs such as “clouds scud above us like flags”, “Up on the slope a fox skulks past”, but really you could open this book at any page and find a beautifully crafted sentence, paragraph, thought or thread. Derbyshire writes in her translator’s note about finding Hoffmann’s “voice” in English (this is particularly important for the opening section of the text, but save the translator’s note for after you’ve read the book – it’s well worth reading it once you’ve absorbed Paula rather than pre-emptively before you spend a few hours with Hoffmann’s family), and though I can’t read the original German, there is something distinctive and consistent in the melancholy, the care, the images, and the crystallisation of years of pain in single breathtaking sentences that mark this out as a superb translation.

I’m delighted that Paula has found its home in English, and hope that the new imprint of V&Q Books will continue to bring us great women’s writing from German; in the meantime, I’ll see you back here next week to talk about Daughters.