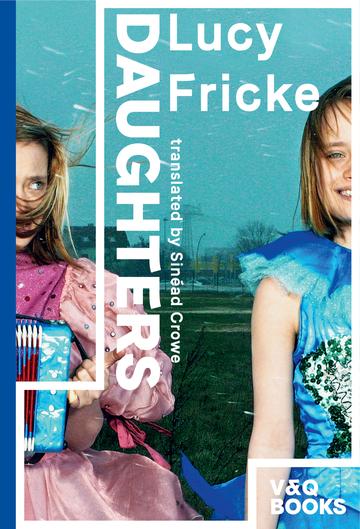

Translated from German by Sinéad Crowe (V&Q Books, 2020)

The new English-language imprint of V&Q Books offers another belter for its launch: following on from last week’s review of Paula (Sandra Hoffmann, translated by Katy Derbyshire), today I’m looking at Lucy Fricke’s Daughters, a book that manages to switch effortlessly between grief and humour and which, in a superb translation by Sinéad Crowe, is one of my favourite books so far this year.

Meet Betty. She’s a writer, recently turned 40, single, grieving, recovering from depression but clear-sighted enough to know that she won’t give up alcohol and adventure to aid her recovery. Betty is our narrator, and one of the most riotously caustic literary companions you’re likely to meet. Betty is best friends with Martha, who is a few years younger and desperately trying to have a baby with her husband Henning (who Betty thinks is the best thing to happen to Martha, though Henning himself considers Betty to be a nefarious influence on Martha). Betty and Martha are going to take us on a madcap road trip through Western Europe, for reasons that start out seeming fairly clear and become more complex as the story unfolds.

As well as a common loss that recurs as a leitmotiv through the narrative, Betty and Martha have another significant connection: they both have disappointing, absent, and pretty useless fathers. More than that: they are both still helplessly bound to those fathers – whether by a sense of duty or by genuine affection – and it is the fathers who become both the instigator and the destination of the daughters’ journey.

The journey itself originally comes about because Kurt, Martha’s terminally ill father, announces that he has booked himself into a euthanasia clinic in Switzerland, and his last request is that Martha take him there because, as Martha puts it, “it’s not enough to get his own daughter to pay for him to die, but he expects me to drive him there too.” Still reeling from a recent accident, Martha feels unable to drive herself, and so ropes in Betty to act as chauffeur and chaperone for a journey that should be morbid but is truly hilarious.

The gang never make it as far as Switzerland. There’s a detour (romantic intrigue and promises broken), an accident, and a clue to the whereabouts of another father long presumed dead. Daughters is a fast-paced and eventful journey that packs an emotional punch, but tragedy is always underscored with humour: for example, of Kurt’s final trip, Betty’s stance is that “the thought of making one’s final journey in a Golf depressed me. I ordered a second pint and a shot”; faced with a set of tall bronze doors, she reflects that “if the doors of heaven are anything like that, I’ll never get in”, and of desperate new beginnings she opines that “At every new stage of life you end up back at Ikea, where every hope begins and ends.”

With two forty-ish women falling apart and taking to the open road, this book could very easily have fallen into tropes of gender and facile stereotypes (there is even an overt reference to Thelma and Louise), but the beauty of Fricke’s narrative direction is that it sidesteps all such conventions. Yes, there is an almost-final scene that could have felt contrived in other hands, but Fricke brings together her various narrative threads so skilfully, and smashes the picture-perfect ending so deftly, that she is always one step ahead of expectation. The friendship between the two women is multi-dimensional: they have a quiet complicity as well as a common grief; each is the only one the other can count on to offer unconditional support, yet they are fully aware of one another’s flaws (Betty is selfish, sensitive only in matters that concern her, whereas Martha “had a tight grip on herself … so tight that she was in danger of strangling herself”). Above all, their bond is very human: Betty says of Martha that “There was no one else in the world with whom I could laugh so uproariously at misfortune” (as literary companions go, one could say the same of Betty herself).

Sinéad Crowe’s translation is edgy and full of verve, and nowhere more so than in the range of lexical expression she uses to reproduce Fricke’s humour: Betty is a “left-eyed bawler”, dangling in Kurt’s car is “a fir-shaped air freshener that had given up the ghost long ago”, and teenage dreams come to an abrupt end with the realisation that “we’d wanted to be champion race-car drivers, and now, twenty years later, we couldn’t even get out of a northern Italian car park.” Crowe excels in communicating Fricke’s sardonic wit, but also allows the pathos to come through in plaintive sentences such as “I had no idea how tenacious grief can be”, “neither of us talked any more about the powerlessness and unhappiness that hounded us every day and were slowly eating away at us”, or the one that most moved me: “Love began with you.”

I love the translator’s notes at the back because, as with Paula, it is revealed after the fact that this seemingly effortless prose is the result of much deliberation. It’s not that I (ever) want the translator to be invisible – hence my love of translator’s notes, and joy every time I see a translator’s name on a book cover – but rather that I prefer it if the process of translation – the brow-furrowing, synonym-searching, come-back-to-it-later or try-it-out-loud to see how it sounds and all the other countless demands that getting to grips with writing a text in another language entails – doesn’t jump out at me as I read. To me, the magic of a great translation (and a great translator) is making a complex task appear effortless. Both Katy Derbyshire with Paula and Sinéad Crowe with Daughters pull that off; I highly recommend that you give V&Q’s new women in translation a whirl.