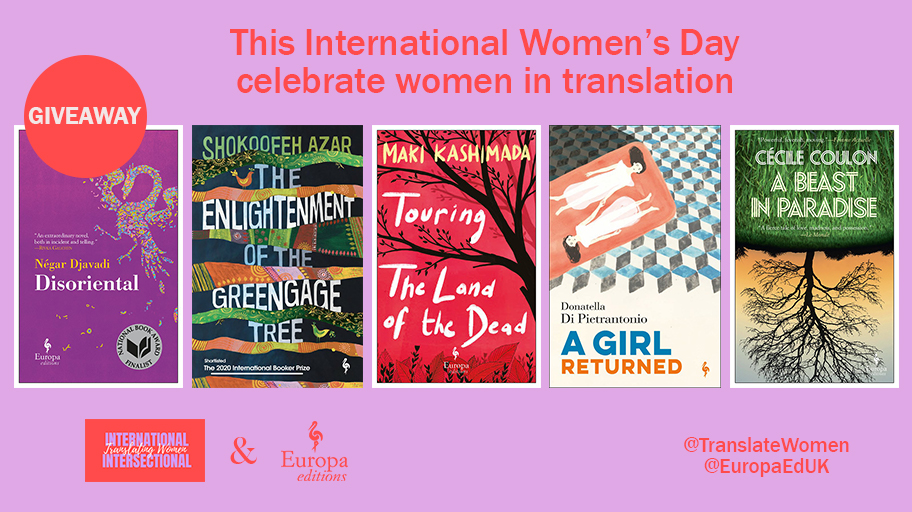

***Don’t miss an exciting Women in Translation giveaway to celebrate International Women’s Day!

Details at the end of the post, or directly in this tweet***

Translating Women: challenging an “invisible mechanism”

The challenge for this year’s International Women’s Day, “How will you help forge a gender equal world?” foregrounds a simple, brutal reality: we do not currently live in an equal world. Women have legal equality in many cultures, but all too often legal and theoretical equality do not map onto real equality of opportunity and experience. This is magnified for women in non-dominant world cultures, as well as for women of colour, working class women, non-cis women, and those embodying other non-normative or non-privileged characteristics – such as sexuality, age and health – that intersect with gender. This social inequality is the fundamental root of the gender imbalance in translated literature: it is widely acknowledged that less than one-third of literature published in translation in English is by women, and this mirrors a more pervasive gender imbalance that has become so normalised that most people no longer even notice it. In an excellent Guardian long read a few years ago, Charlotte Higgins exposed how patriarchy thrives on this normalisation of social hierarchies, functioning as “the invisible mechanism that connects a host of seemingly isolated and disparate events, intertwining the experience of women of vastly different backgrounds, race and culture, and ranging in force from the trivial and personal to the serious and geopolitical”.

Watch my 3-minute International Women’s Day video here!

A key component of this inequality, or of the invisible mechanism of patriarchy, is what Caroline Criado Perez describes in her award-winning Invisible Women: Exposing Gender Bias in a World Made for Men as the “default male”, a way of viewing the world that always uses men as the baseline indicator, the universal “norm”, and which is harmful to women (not only socially and psychologically, but also in some cases physically). There are also less quantifiable characteristics, such as class, and simply less quantified characteristics, such as race or sexuality, that intersect with gender and are further marginalised. Women writers – particularly non-white, non-middle-class women writers – face hurdles in their own country, and these are amplified when it comes to translation. It is more likely that publishers will promote their more successful authors to English-language publishers, and with the invisible mechanisms of patriarchy at work across the globe, the chances are that these prize-winning or best-selling writers will be men. It is, therefore, crucial, that we challenge this system instead of passively allowing it to perpetuate itself for, as the organisers of International Women’s Day remind us, “a challenged world is an alert world”. By not questioning existing structures, we both perpetuate and normalise the inherent bias they carry; if we stop at an argument about the inequality being in the country of origin, then we can only ever reproduce and enable structures that represent only half a world.

From challenge comes change

Translation by its very nature invites communication and understanding between peoples and cultures. At a time when “culture” is too often reduced to nationalism and stereotype, it is essential to advocate for greater diversity and inclusivity: when women are left out of “culture”, the notion of culture itself is impoverished. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie states in her brilliant manifesto We Should All Be Feminists, “Culture does not make people. People make culture. If it is true that the full humanity of women is not our culture, then we can and must make it our culture.” If culture preserves a people or nation and ensures the continuity of civilisation or nationhood, then any culture that does not offer true equality to women, or that does not actively seek to achieve diversity and inclusivity, can only ever perpetuate harmful notions of what humanity is. Ngozi Adichie’s insistence on “the full humanity of women” is also key here: “women” cannot only be understood as heterosexual women, cis women, white women, straight women, or any other dominant characteristic that can be conflated with “womanhood”. Rather, the “full humanity of women” must include minority groups that stretch beyond gender – while women are not a minority, they are still secondary, but we must also remember that within this secondary group are minorities that are often overlooked in feminism and gender politics. What is published in translation, and which books into translation make it onto literary prize lists, is a means for writers from other cultures to enter the Anglophone literary ecosystem, influencing English-language readers and writers and enriching our cultures. So it is vital that there is diversity of representation in what makes it through in translation, otherwise we allow the inequality to persist.

Choose to Challenge: we can all make a difference

You don’t have to wait for amazing books by women from other cultures to come to you; why not actively seek them out? As And Other Stories’ Nicky Smalley reminds us, after all the hurdles they’ve had to overcome to make it into English, the chances are you’ll be rewarded with an amazing read. You can read about my favourite books of 2020, or check out the reviews section. If you’ve enjoyed a book by a woman writer in translation, talk to people about it: pass on your recommendations whether it’s to one friend or to hundreds or thousands of social media followers. And when you ask others – friends, family, teachers, booksellers, social media contacts – for recommendations, if no women are suggested then ask explicitly for them. The more we gently challenge perceptions of “normality”, the more these perceptions are likely to shift towards greater inclusivity, and the more these books appear on bookshelves, the more normal it will be for them to have their place there. If we all make active and conscious changes in our own small corner, then we might get closer to an equal world.

Twitter women in translation giveaway!