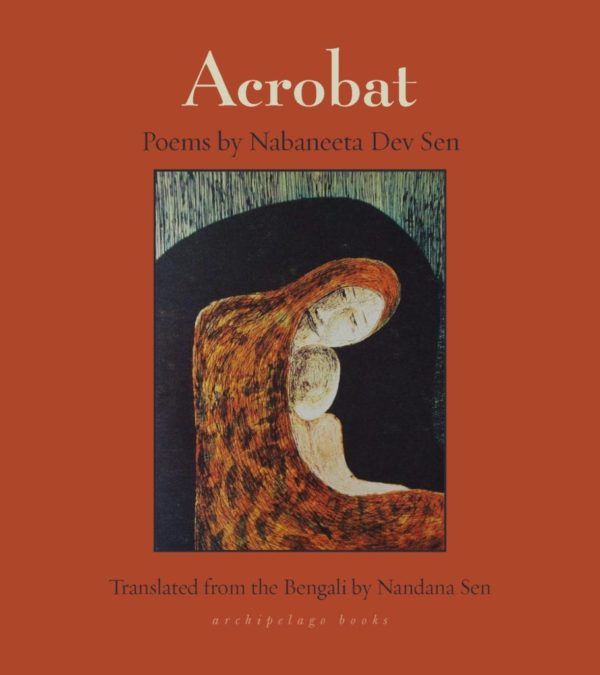

Translated from Bengali by Nandana Dev Sen (Archipelago Books, 2021)

Acrobat is a collection by Bengali poet Nabaneeta Dev Sen, some translated by the poet herself before her death, but mostly translated into English by her daughter Nandana Dev Sen as a poignant and passionate exchange between mother and daughter. As a collection, the poems are vibrant and full of longing – whether for love, for children, for lost youth, or for prolonging life.

As I was reading Acrobat, I felt I probably wasn’t the “right” reviewer for it. I don’t know whether this was because of the point at which I was reading it, or whether it was more to do with my own lack of confidence in understanding poetry. In any case, in my review I’ve decided to focus on the poems that I liked best, the ones I found most beautiful or moving, with the acknowledgement that this constitutes an entirely subjective and inexpert response, and might cover only a fraction of what the collection could mean or represent.

The first stanza that made me stop and read again was this ending of “The Lamp”:

“Just one more page left

one more paragraph, one more sentence—

give me one more word, dear nurse,

just one more day.”

Many of the poems deal with this desire to hold on to life, to live each moment fully and to catch it in a poem; “Time” talks of five minutes stretched into a lifetime, “Unspoken” understands “forever” as “today”, “Right Now: Forever” exclaims that “Time has not the power to extinguish me”, and “In Poetry” urges us to “Stay alive … Stay awake in every line”. This was the theme that most stood out to me through the collection, and it is particularly plaintive given that this is a posthumous publication: time is also presented as relentless, a snatcher of youth and a cruel harbinger of decay.

This multifaceted approach to theme is also present in the representations of love: it is by turns joyful (“Beyond it all,/ Stands a mountain of laughter, of joy./ On that mountain, I will build a home with you/ One day”), painful (“He leaves his footprint in my eye”), tender (“Let my heart/ nurse your aching body”) and wistful (“We would meet, that was the plan. /Look, my love, I am still here”).

If love is a celebration, a tenacity, and an emotion experienced in the present, it is also a fear, a bitterness, and the painful awakening of memory, such as in the very brief poem “Sound: Two”:

“Like an old alarm clock

You start ringing in my heart

I shut my ears tight”

This rejection of love, or closing of the heart, is echoed elsewhere in the collection: “That Girl” is a case in point and was one of my particular favourites, but also epitomises what I mean when I say I’m not sure I was the right reviewer for this collection. I think “That Girl” is beautiful, profound, and extremely moving, but every time I try to write why, my words feel inadequate. My best attempt is to say that it’s about youth and the conflicting sensations of fear and power that it brings, about the walls we build around ourselves and what we lose because of it, and it’s about time catching up with us, a life breathed out and sighed away in the space of a couple of pages.

I think the conclusion I’ve reached is that for me poetry is something I respond to with my gut rather than my mind. Overall I preferred those poems where a rhyme wasn’t sought in the translation, and I liked best the pieces that blend the ferocity and tenderness of love and yearning that for me defines the collection. Acrobat is moving in both content and context: translated with great heart by the poet’s daughter and published posthumously, it is a two-way love story between generations and a celebration of life in all its complexity and contradictions.