Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Helen Vassallo

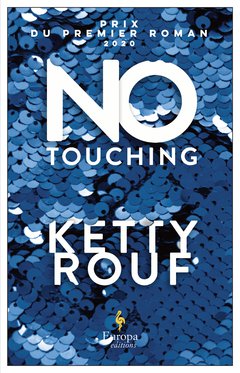

3 December 2021No Touching is a story of everyday drudgery and unexpected empowerment, dealing with questions of female agency, desire in all its forms, and the extent to which self-worth comes from the way we see our image reflected in the eyes of others. It is narrated by Joséphine, a high school philosophy teacher in the suburbs of Paris who decides to shake up her predictable life by taking pole dancing classes: by a series of coincidences, Joséphine ends up landing a job in a high-end strip club in central Paris, and starts a new nocturnal life as dancer Rose Lee.

Rose Lee is described as a rebirth for Joséphine, a new life, or a new chance at life: “Did it really take me thirty years to be born? Yes, maybe. I dreamed of being the kind of sexy woman who gets men hard, drives them crazy, the kind who’s not afraid to show her ass and spread her legs.” Yet this new beginning is precisely the concern I initially had with the story: Joséphine only comes to love herself when she feels that she is sexually desirable. However, her self-awakening (“I hated this body for so long. But now it’s my personal celebration”) made me feel much more sympathetic towards her in this respect: Joséphine has gone from feeling that “My body was trying to escape, it had stopped belonging to me” to loving being in her own skin, and taking pleasure in her reflection – and so if this is what it takes for her to feel that she inhabits her body instead of remaining estranged from it, then perhaps that should be celebrated rather than judged. Indeed, for every time that Rouf seems to be suggesting that Joséphine can only feel a sense of worth if she is arousing a man (for example, she mentions the “frequently uncomfortable positions I have to contort my body into in order to be desirable to men”), she then blindsides by showing how for Joséphine this is liberating (“Putting on the mask of Rose Lee turns me into a free woman”).

Joséphine is frequently scathing about her contemporaries, who she sees as living little lives and settling for banality rather than yearning for fulfilment (“Small life, small joys”, she comments of their countdown towards the end-of-school bell each day, and describes herself and her colleagues as “brought together in an obscene display of our lack of drive and passion”). The fact that she includes herself in this criticism rescues it from being too judgemental, and so I tried not to get too bogged down in stereotypes of navel-gazing middle-class French writers – after all, at least Joséphine is doing more than simply talking about her dissatisfaction. And her impassioned speech to her students about how the system wants them to remain in ignorance and they are blindly marching towards their inglorious futures was a particular highlight, as was her exposure of the bureaucratic injustices of the paths towards advancement in the French education system. Tina Kover’s use of register always impresses me: Joséphine’s self-flagellating turns of phrase (“God, what a loser I am!”; “the only time of the year when I don’t want to barf up my whole life”) and sardonic observations about administrative frustrations (“The whole overarching failure of homo technologicus, summed up in a few sheets of paper mangled by a malfunctioning photocopier”) are beautifully rendered, as is the voluptuousness of her dimly-lit dances and the harshness of the bleary-eyed sunrises.

An interesting feature of Joséphine’s story is how her love of philosophy drives her forward in her life choices: “Knowing how to live means choosing the ideas that won’t ruin us. That’s how philosophy can rescue us from the unhappiness of existing.” If dancing in a high-end strip club has rescued Joséphine from “the unhappiness of existing”, then this itself has come about because it is an idea that “won’t ruin her”. We discover more about her passion for philosophy in an epistolary relationship she develops with one of her students, Hadrien, an exchange that renews Joséphine’s sense of purpose in her day job. Joséphine’s other significant relationship is with Martin, a fellow teacher with whom she has a platonic but potentially romantic complicity. There is no clear resolution to this potential (which I appreciated): Martin represents the life Joséphine wanted to leave behind, but will her time as Rose Lee make her more appreciative of the tenderness she craves and that he might just offer her, or has her alter ego drawn her too far away from the kind of everyday satisfaction and stability that Rose Lee seems to scorn? No Touching is an engaging and original story, pulsing with fantasy and dragged along by reality, a story of two identities struggling to co-exist in the same person – I’ll leave you to find out for yourselves whether Joséphine or Rose Lee has the last word.