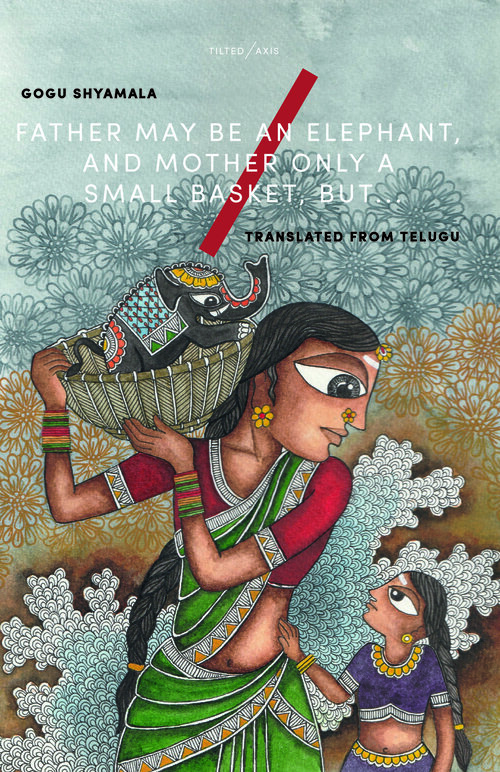

Translated from Telugu by Diia Rajan, Sashi Kumar, A. Suneetha, N. Manohar Reddy, R. Srivatsan, Gita Ramaswamy, Uma Bhrugubanda, P. Pavana, and Dugginala Vasanta (Tilted Axis Press, 2022)

It’s no secret around these parts that I’m a Tilted Axis Press superfan. From their mission to dismantle structures of hierarchy and exclusion in the publishing industry to the books they publish to work towards this, they represent the best of independent publishing. So I was delighted to be invited to review their latest book, a collection of feminist short stories from India.

Father may be an elephant, and mother only a small basket, but… is a beautiful, humbling, necessary book. I’ve rarely read anything that made me so acutely aware of my own ignorance and privilege, but that didn’t attempt to make me feel small because of that. It’s the kind of book that inspires me to be better, to open my eyes, to shake off my own biases. Is it the kind of book I couldn’t put down? Possibly not. But then I don’t think it’s meant to be a page-turner. Rather, this collection of short stories is a slow-burner, one that stayed with me each time I put it down rather than that had me racing through.

The stories in Father may be an elephant, and mother only a small basket, but… focus on daily life in poor communities: these are tales of dissidents and resistants, stories of outsiders and underdogs, people born into “the caste that makes slippers for everybody” while their own feet remain bare. In all of the stories the caste system is accepted by protagonists as fundamental truth – the mere mention that, hypothetically, a boy from the baindla caste could marry a girl from the reddy caste results in a near-lynching. Yet the greatest injustice of the caste system is its abuse by cynical leaders who do not want the workers to understand the power they possess, or their importance in the continued functioning of this rural and agricultural life (for, as we are reminded, if everybody is educated, who will do the work?)

Tying in with the rural and agricultural focus, water is sacred in these stories: one of my favourites is narrated by a bounteous and forsaken village tank, while another opens with the quietly ominous statement that “the overflowing stream wound itself around the village like a snake winds itself around a man”. Land is precious and fiercely defended, yet it can be withheld by the village elders, and the greatest shame is being exiled and banished from land that is only ever provisionally and precariously owned. The village, and the community that makes it function, is at the heart of all the stories, yet this is not always a tranquil or co-operative environment: children are bonded to labour, people are cast out by their own families for becoming “impure” from touching those of a lower caste, dogged belief in luck and omens guides many of the decisions about who is included and who is excluded from the community.

There is a specifically female perspective in many of the stories: mothers struggle to get their children educated, to make good marriages for their daughters, to keep art and culture alive. They are left powerless and penniless when husbands die, beaten while husbands are all too alive, or sent away to avoid the fate of belonging to the village’s men; when they show strength they are called witches and ostracised. Their vulnerability is foregrounded implicitly in some cases, and explicitly in others (as one elder explains to an overly dismissive boy, “There is a special way in which girls are insulted or looked at, and it is very painful”). The short essay on Shyamala at the end of the collection indicates that her own experience has inflected many of the situations in the stories, including the vulnerability of children, the focus on hard work and dedication, and the importance of education.

The language of the translation is rich in unfamiliar and culturally specific terms (usually referring to events, roles or social groups) – there is an extensive glossary at the back of the book but I rarely consulted it while reading the stories, preferring to try to understand them from context and then looking them up later. I didn’t always get it right, but I did particularly appreciate NOT having the explanations as footnotes, which I find intrusive. There are also a number of interesting instances of translation that foreground the foreignness of the text. A reference to “the evil gaze” seems more evocative of ill wishes than the standard collocation “the evil eye”, and expressions such as “will we cut our own throats just because the knife is golden?” or “you know that the fingers of the hand are not equal” enrich our own language by infusing it with the imagery and traditions of the original Telugu and refusing to put English sayings in the mouth of these Dalit villagers. This kind of approach to translation can be destabilising, rejecting the insistence on familiarity and bringing texts closer to the reader that is so often assumed to constitute “good” translations. However, in one of my favourite pieces of writing about translation, Madhu Kaza invites us to abandon our ingrained insistence on “faithful” translations, questioning how “errant, disobedient” translations (those that remind us of a text’s foreignness) might better serve us. Leaving many terms in their original form and including expressions whose meaning might be clear but whose construction is not familiar shows a brave refusal to package these stories into a neatly digestible form, instead inviting us to approach translation as a practice of hospitality that, as Kaza suggests, “acknowledges that the host, too, will have to be changed by the encounter”. This is a collection whose translation does not seek to erase its otherness: it invites us to listen rather than co-opt, to adapt rather than to expect adaptation, and to remake the way that we choose to locate ourselves in the world.

Review copy of Father may be an elephant, and mother only a small basket, but… provided by Tilted Axis Press