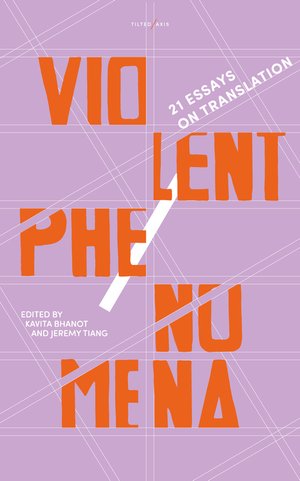

Edited by Kavita Bhanot and Jeremy Tiang (Tilted Axis Press, 2022)

I have long been looking forward to the publication of Violent Phenomena, a collection of essays exploring the possibilities of a “decolonised” translation. It was probably my most anticipated book of the year, from one of my favourite publishing houses, and still it managed to exceed all my expectations. This exploration of the power dynamics and colonial legacies of literary translation is a call to action, a call to accountability, a shattering indictment of white European privilege, and an absolute must-read for anyone interested in new ways of considering translation. Compiled, as editors Kavita Bhanot and Jeremy Tiang note, in a “spirit of defiance and resistance”, the individual essays echo and resonate with one another, coming together to form a radical shakeup of what we take as given and/or unchangeable. Individually and collectively, the authors tease out common threads of prejudice and isolation within the context of translation into English: despite commonly held and idealistic assumptions about translation being a site of welcoming and embracing otherness, in Violent Phenomena it is exposed as being a space where many can feel unwelcomed, unrepresented, and eternally on the margins.

I want to start by acknowledging that I might make mistakes in the way I write about this volume, because the painful experiences exposed within it are those from which my whiteness spares me; any of the (frequently inaccurate) assumptions about my cultural identity and heritage do not usually close doors to me because they focus on my whiteness, my European-ness, my assumed “belonging”. In this collection of essays, we see the everyday reality for people whose “legitimacy” is constantly called into question because of the colour of their skin, assumptions about their relationship to the English language, or connection to a marginalised culture. As I write this, I question whether I am the “right” person to write about Violent Phenomena, and yet if I don’t write about it for fear of getting it “wrong”, then I only become complicit in the ongoing silencing of marginalised voices. So here goes, and if I am clumsy in my responses to being confronted with a reality that I have not experienced, that is my deficiency and no reflection on the collection of essays in Violent Phenomena.

The first thing that strikes me as I think back over my reading of the book is the discomfort I felt at many of the essays. I see this as a good thing: I don’t think this is meant to be a comfortable or reassuring piece of work. Indeed, I’d say that it is as uncomfortable as it is necessary. At the end of their introduction, Bhanot and Tiang describe the impossibility of decolonising as being anything other than a “violent disruption”, because it is a fight against an oppressor who in theory often no longer exists, but in practice is present in everyday attitudes, encounters and exclusions. And so it is the case for literature in translation: anyone can translate anything from anywhere, but in reality doors are consistently closed to non-mainstream voices, to people (authors, translators, protagonists) who are, as Madhu Kaza notes in her essay, “not a good fit”.

The collection opens with an extended version of a piece published by Gitanjali Patel and Nariman Youssef in Asymptote last year. Patel and Youssef explore the ways in which translators of colour are marginalised in the Anglophone literary translation world, and how this is reflected in “the tendency to view ‘otherness’ as a challenge or a threat” that can erase diversity by hiding behind “a fluency imperative” that assumes only one version of acceptable English. The barriers – both explicit and insidious – to translators and translated texts from non-mainstream languages and cultures are picked up and amplified in other essays of the collection: a particularly enraging episode is Sawad Hussain’s depiction of the patronising “tickbox” approach to diversity that saw one publisher keen to pick up one of the marginalised authors she champions, only to assign Hussain – an experienced and well respected translator – two older white male mentors to co-translate so that they could also tick the box on their new commitment to a mentoring programme. And when you find out why Hussain translates from Arabic rather than her first learned language (French), you’ll find it shameful.

In fact, for someone who believes passionately in social justice, it’s disturbing to see how little of it there is in the experience of the contributors to this volume. From the erasure of the tragic history of the transatlantic slave trade in the “dystranslation” of M. NourbSe Philp’s Zong! (discussed in a raw conversation with Barbara Ofosu-Somuah) to the refusal to see Armenian literature in English translation through any other lens that that of the Armenian Genocide (Shushan Avagyan), the authors repeatedly confront us with situations in which the western receiving context resolutely refuses to see history on anything other than its own (colonial) terms. This is borne out in Anton Hur’s indictment of the “mythical English reader” – a lazy trope used to fulfil two functions: firstly, and more globally, to insist that translated literature be made more familiar and accessible to the target audience, and secondly, more personally, to gaslight Hur – who is, as he points out, an “English reader” himself – by questioning his own use of the English language because “English reader” is a thinly veiled code for “white reader”.

This persistent erasure of difference leads many contributors to reference Édouard Glissant’s notion of the “right to opacity” – to not attempt to be easily understood, and instead of bending to Anglophone expectations that are steeped in the history of imperial dominance, to invite Anglophone readers to venture out of that restrictive mentality and move towards the text and author they are reading. In this vein, Madhu Kaza’s essay on her complex linguistic and cultural heritage reveals how falling back on such tropes (in her case, acknowledging repeated use of the phrase “not a good fit” in a variety of contexts) hides unexamined bias, allowing cultural gatekeepers to keep perpetuating a world that is familiar to them rather than attempting to understand why something – or someone – might not “fit” this world.

Throughout the collection, authors describe acts of resistance to these exclusions that include deliberately using language in a way that preserves it from the desire to package and label (as outlined by Khairani Barokka), that contests the understanding of translation as “a transparent window into another cultural context” (Hamid Roslan), or that refuses to “explain” a term by finding an (often inadequate) equivalent (Elisa Taber). From these individual experiences stems a collective challenge to the kind of “fluency” that is used as a facile yet immutable yardstick by which language is judged and difference systematically erased, a challenge that opens up spaces of encounter and understanding much more profoundly than by bringing everything neatly and recognisably to the (mythical) English reader.

There is one significant lesson for those of us not in such marginal positions: we need to unlearn things that we did not realise we have been conditioned to accept. This is a position I find myself in over and over again the more I research the processes by which translated literature makes it through into English, and it’s an uncomfortable one. Violent Phenomena is not only a landmark collection of essays, with all the intellectual and artistic weight that such a statement carries, but also a manifesto, a disruption, a challenge to improve and expand the values, institutions and structures by which we measure our world(s). And in this context I want to give the last word to Kaza, and align myself with her invitation to recognise that “in reading across distances what we gain is not simply more company, but an opening for solidarity”.