Becca Parkinson and Zoë Turner work at Manchester-based publishing house Comma Press, where Becca is Engagement Manager and Zoë is Publicity and Outreach Officer. Comma Press is dedicated to publishing books that transcend cultural boundaries, and is known for an activist commitment to commissioning short story anthologies and literature in translation.

The translation imprint of Comma Press was set up in 2007. How has it evolved over the last decade?

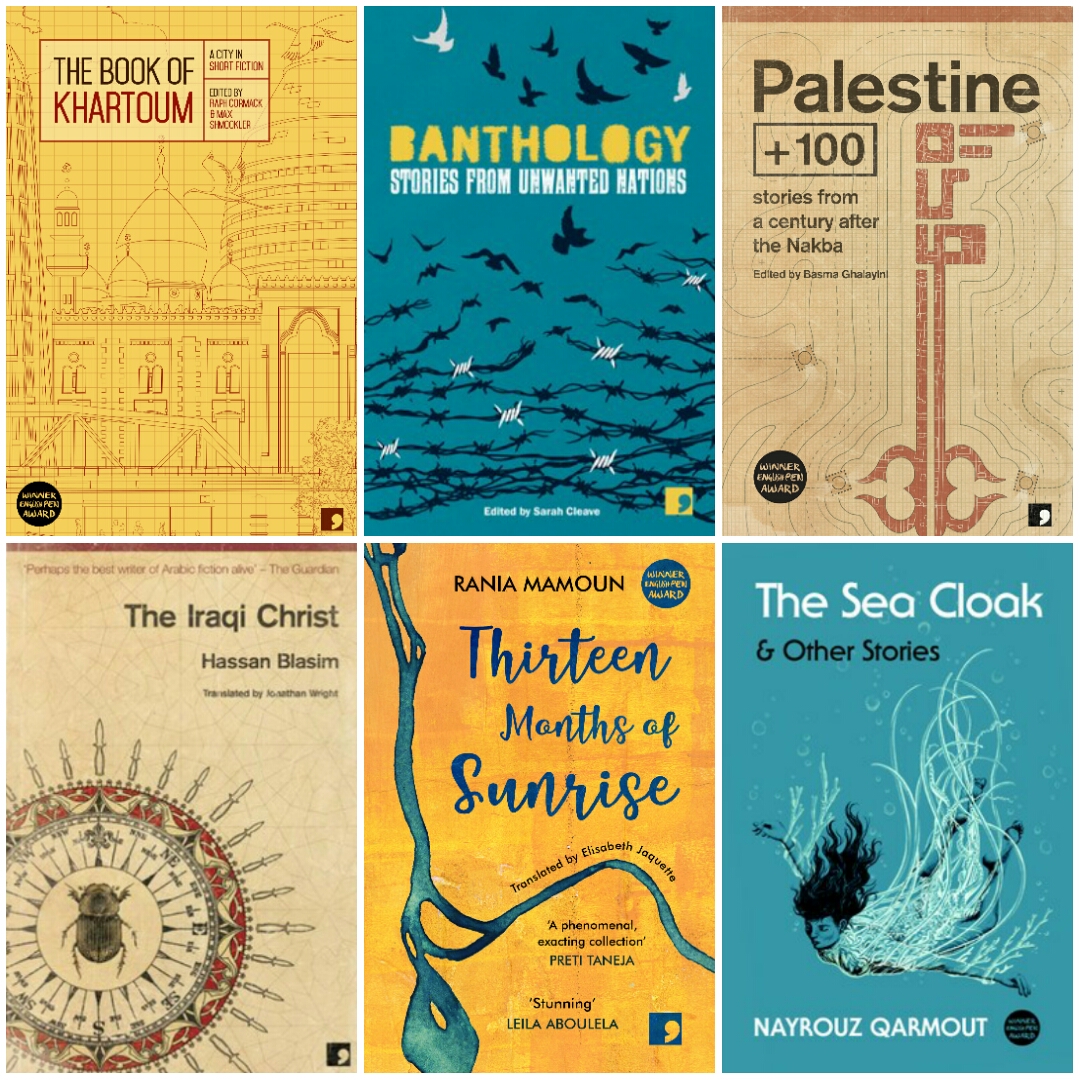

Becca Parkinson: We started off with regional anthologies, which looked at predominantly European cities and had different themes. More recently, we’ve developed the Reading the City Series and we have a commissioning arm for projects such as the + 100 series which is Arabic science fiction. We’ve done Iraq + 100, a collection of short stories imagining Iraq 100 years after the American and British-led invasion, and Palestine + 100, stories set 100 years after the Nakba. The idea of these anthologies is to find authors, and in most cases these anthologies have led to us publishing single authors: for example, with Madinah: City Stories from the Middle East we found Hassan Blasim who is now one of our most successful authors; he won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2014 (for The Iraqi Christ, translated by Jonathan Wright). With The Book of Khartoum, we worked with Raph Cormack, an editor and translator who we knew was deeply embedded in modern Arabic literature and who helped put together the project. We got PEN funding for The Book of Khartoum, which is very important, and we found (author) Rania Mamoun. This year we’ve published her single-author collection Thirteen Months of Sunrise (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette); we might not have found her if it hadn’t been for that anthology. Our translations are what we’re known for and recognised for with other publishers, the press and the public. As a small independent publisher we can work around one-off events and we can commission in response to modern societal problems – as we did with Banthology, which was commissioned in response to President Trump’s travel ban – in a way that a lot of larger corporate publishers perhaps can’t.

Do you have a specific quota of translated work in your catalogue? And are there specific areas or writers that you prioritise?

Zoë Turner: There isn’t a specific quota, but it’s just so ingrained now. Annually we publish about 50% translated works. And we prioritise languages that aren’t often translated; we haven’t done The Book of Paris, just because there are so many translations from French. And even if literature translated from Arabic might be fairly common, Sudanese literature isn’t.

Becca Parkinson: We do survey our readers annually, which is part of our Art Council remit, and gives us a chance to ask our readers what they want to see. We also have to go with our own instincts: for example I worked on The Book of Tbilisi, and bringing ten authors from Georgia into English is a fascinating process. I’d never read any Georgian literature before that project, or any Latvian literature before I worked on The Book of Riga. It just shows that there’s a gap there; there’s a wealth of literature from these countries that could be brought into English. And short stories are inherently portable and fairly easy to translate. It doesn’t require vast amounts of context either to establish a story or for the reader to understand it culturally, nor vast amounts of backstory or history, and as such it travels light. Historically, the short story has moved across geographical boundaries and been very transnational in its influence. The short story is, as our editor Ra Page says, the most “smugglable” form of literature, the most transportable form of literature. And it means that we get a diversity of voices in terms of age, gender, and outlook on life. It also means that we can have established authors alongside emerging authors in our anthologies.

What do you perceive as the greatest challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature or in the publishing industry more generally, and how might we overcome these?

Becca Parkinson: Women are underrepresented in every way, whether it’s in publishing, reviews, translation… There are initiatives like the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation and the Women’s Prize for Fiction which are trying to rebalance that, but it still exists. As you know, translated literature only makes up 3.5% of the market, which isn’t a huge proportion, but it’s growing, and in an ideal world women writing in translation would have an equal footing with men. It’s something we’re very conscious of when we’re commissioning. With our Reading the City anthologies, we try to find a 50-50 split of men and women with the authors and the translators if it’s possible. It’s not always possible: there are some countries or cities where we go and we simply can’t find the women writers, sometimes because they’ve been so suppressed, or because they’re scared.

Zoë Turner: The bias isn’t to do with women translators, that’s quite healthy; it’s more the authors who are being translated. Much of what makes its way into English translation does so by connecting with something in the news, so it’s something that the target market understands, but that’s a very media-generated appetite and feeds into the fact that men dominate the news and the media. So people end up seeing a country through a male gaze in terms of politics, and then end up looking for men writing about that.

Becca Parkinson: We’re seeking to redress that bias in any way we can. We’re working on a new project with Hay Festival and Wom@rts: it’s called Europa 28 and it’s the biggest anthology we’ve worked on; it’s scheduled for publication in March 2020, and launching at the Hay Festival. It’s being edited by our colleague Sarah Cleave and translator Sophie Hughes, and it’s an anthology by 28 women writers from Europe, writing about their vision of the future of Europe. We’ve never done an all-female anthology before so we’re very excited.

As a team, we’ve discussed ways of overcoming bias, and we think that if literature festivals are leading the charge as well as publishers, they can do the most to help address it. We know this from working with Hay Festival and working with Edinburgh International Book Festival for the last few years. In the UK many book festivals aren’t international, because festival organisers can see all the difficulties of bringing over authors from other countries. But Nick Barley at the Edinburgh Festival has helped us enormously with getting authors into the UK. We’ve had visa applications rejected time and time again; for example last year we applied for a visa twice for (Palestinian author) Nayrouz Qarmout. It was rejected by the Home Office, so the festival brought in a big group of politicians and journalists; the visa was granted, and Nayrouz made the festival and had an amazing event with Kamila Shamsie. Edinburgh was leading that; they got more than twenty visa rejections overturned. And if more festivals invited over authors who aren’t from the UK and fought those visa battles, there wouldn’t be a news story about visas getting turned down. That shouldn’t be news, it shouldn’t be happening in the UK, but this insular atmosphere at the moment is focusing on British authors. It’s wrong, it’s the opposite of what we should be doing. So Edinburgh and Hay help us by having a diverse programme, inviting authors who have been translated into English – or even if they haven’t yet been translated, inviting them over to the UK so they can have that platform. We fear it may become increasingly more difficult to bring authors over, which will discourage publishers from publishing work from those countries. So there are things that festivals and publishers can be doing with authors that could help redress those biases by having women in translation events in the UK. But we need the infrastructure to support that.

Zoë Turner: And we need to publish these works, to shake people out of their comfort zone, because otherwise they’ll never seek out these books. Two of our recent books, The Book of Khartoum and Thirteen Months of Sunrise, just made The Guardian’s list of top ten books about Sudan. That’s great, but why can’t they be on a “normal” list of top ten books? It’s the same with separating women writers – why put women’s writing in a separate category? People will automatically go for something that they think they will relate to. And if we’re not being shown that we can relate to these works from other cultures across the world, if they’re being “othered” in our narratives, then without even thinking about it people won’t pick them up.

Do you perceive an increase in the number of translated works making their way into English?

Becca Parkinson: Yes. I’m quite optimistic. I think people are being more exploratory. We need to get people over the idea that if a book is translated it’s going to be difficult. Bookshops and libraries could give us a bit of a hand in the marketing: you need a bookseller or a librarian or a reviewer to pick a book up and say ‘this is special’ and add their voice to yours. But especially as an indie, you’re going up against much bigger dogs in the industry, and then you’ve got Amazon, you’ve got a lot of people fighting against you. You’re not getting your books on the Waterstones front tables, you’re not on the Amazon homepage, so how do people find you? But the audience is there, and it’s growing.