Nicci Praça has had a long and successful career in publishing: she was Head of Publicity for Quercus, where she launched MacLehose Press and did the PR for Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy. Then she moved to freelance work for independent publishing houses, starting with And Other Stories and then helping to launch Fitzcarraldo Editions, where she stayed until the beginning of 2019. During that time she also worked with a number of other independent publishers, including Les Fugitives, Influx Press and Istros Books, as well as helping to establish the Art of Translation events series at the Caravanserail bookshop and promoting the Republic of Consciousness Prize for Small Presses.

Nicci currently balances her freelance PR work with managing the new Amnesty International Book Shop in Kentish Town.

Throughout your career in publishing, have you perceived an increase in the number of translated works that are making their way into English?

Yes. When I first started in 2001 I was working in commercial fiction for a commercial publishing house, and we didn’t publish much translation. Five years later I moved to Quercus, which was then a very young independent publishing house; they had just won The Costa Book Award, and shortly after that Christopher MacLehose was brought in to publish mainly literature in translation. Up until that point, my contact with literature in translation hadn’t been significant; all the books I had read had been classics that had been translated a long time ago. I started working with translated literature in the crime genre, and I found that although publicizing literature in translation to literary editors was quite difficult, publicizing literature in translation to crime reviewers was easy; they were very open to looking at what was happening in other cultures and in other countries. Their openness really helped: by the time Christopher (MacLehose) published The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, which I worked on, the crime community had already accepted Henning Mankell (author of the Wallander mysteries) and Peter Høeg (author of Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow), so when I pitched Stieg Larsson to them they were very open to the idea. But when I pitched Stieg Larsson to the literary editors, I had to turn it into a news story that they would be interested in. By the time the paperback came out, everybody wanted to read it. And a lot of that excitement had come from the initial response from the crime community that had reviewed the hardback and been enthused by it. After working on that trilogy I noticed a distinct rise in the interest in literature in translation from literary editors. And since then I’ve found literary editors more open to discovering new voices from different countries and different languages.

Within the headline figure, the much-quoted 3.5% that represents the proportion of literature in English that is in translation, do you see anything changing?

I do. I see translated literature growing, particularly if our borders shrink, but especially because younger generations, from the millennials down, are keen to find out about what’s going on around the world. The Internet has helped with that, and people’s tastes seem to be broader, which is great. I think that there will be more of a hunger for literature in translation; it’s going to keep growing. People aren’t necessarily finding out about literature in translation through the national media, but they are discovering literature in translation through Instagram, blogs, Booktube, Twitter, and particularly from online literary journals like Asymptote, Guernica, Words Without Borders and so on.

How do the publishing houses that you work with identify translated works for commission?

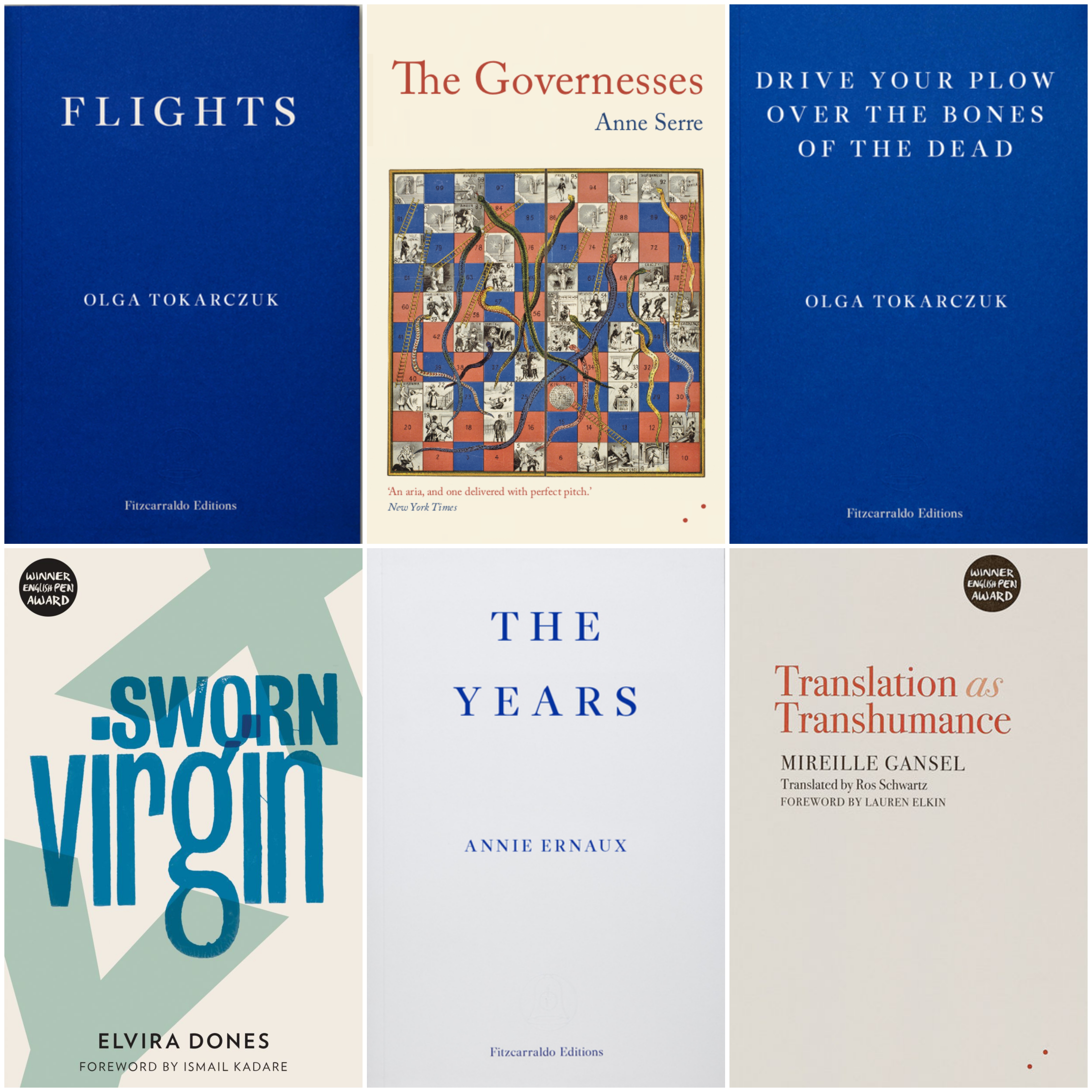

It works in various ways. They’re approached by agents in some cases, and by translators in others; for example, both Antonia Lloyd-Jones and Jennifer Croft have been great champions of Olga Tokarczuk. And when they’re really passionate about somebody they don’t stop, so that’s probably the strongest avenue where publishers find literature in translation. They also find new books from the authors they’ve published in translation, by having conversations with them about what they’re reading and what they recommend.

You mentioned Olga Tokarczuk; could we talk about Flights, translated by Jennifer Croft, and the journey from pitch to publication and then ultimately prize-winner? [note: this interview took place before Tokarczuk was awarded the delayed 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature].

Jennifer Croft approached Jacques Testard at Fitzcarraldo Editions and spoke to him about Flights; she’d been translating it and felt very passionately about it. Granta had published Tokarczuk’s House of Day, House of Night (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones); it had got coverage in the UK, and there was also a chance that Olga might be shortlisted for the Nobel Prize for Literature. These things make a difference when a publisher is trying to decide whether to publish an author. By the time I came to Fitzcarraldo Editions, Flights had already been purchased and was going to be published in May 2017. Poland was the guest of honour at London Book Fair that year, so Olga had been invited as part of that initiative in April 2017. The London Book Fair managed to get her interviews and meetings with Claire Armistead at The Guardian, who has been a great champion of Olga. Olga also met Rosie Goldsmith, Joanna Walsh, Katherine Taylor; these people are important influencers, not only in publishing but also in literature in translation. She also had a very well-respected translator, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, championing her work and offering to interpret for her at events. So by the time she came back to launch Flights she already had a groundswell of support. Then early in 2018 she was longlisted and then shortlisted for the Man Booker International prize, and they have quite a heavy publicity schedule; all of the publicity that had happened from the previous year through to April 2018 was already quite significant by the time she was shortlisted for the MBI. Then she won, and that just catapulted her to a completely different level, one which is quite rare for a writer from another country whose books are published in translation.

There has been a beginning of a move away from Eurocentrism in translated literature. How do you perceive that shift, and do you think it might change with the current political climate?

These shifts happen all the time; marginalised languages become very fashionable during specific periods. For example, two years ago Korean literature really exploded on the publishing scene: it was helped by the publication of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, translated by Deborah Smith, but also Korea had been a London Book Fair guest of honour. So there are patterns where a certain country is the guest of honour and UK publishers are exposed to publishers within those countries and to translators promoting literature from that country. The challenge is to keep these languages at the forefront and continue to publish them.

Do you perceive there being any challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature? And if so, what do you think might be done to overcome them?

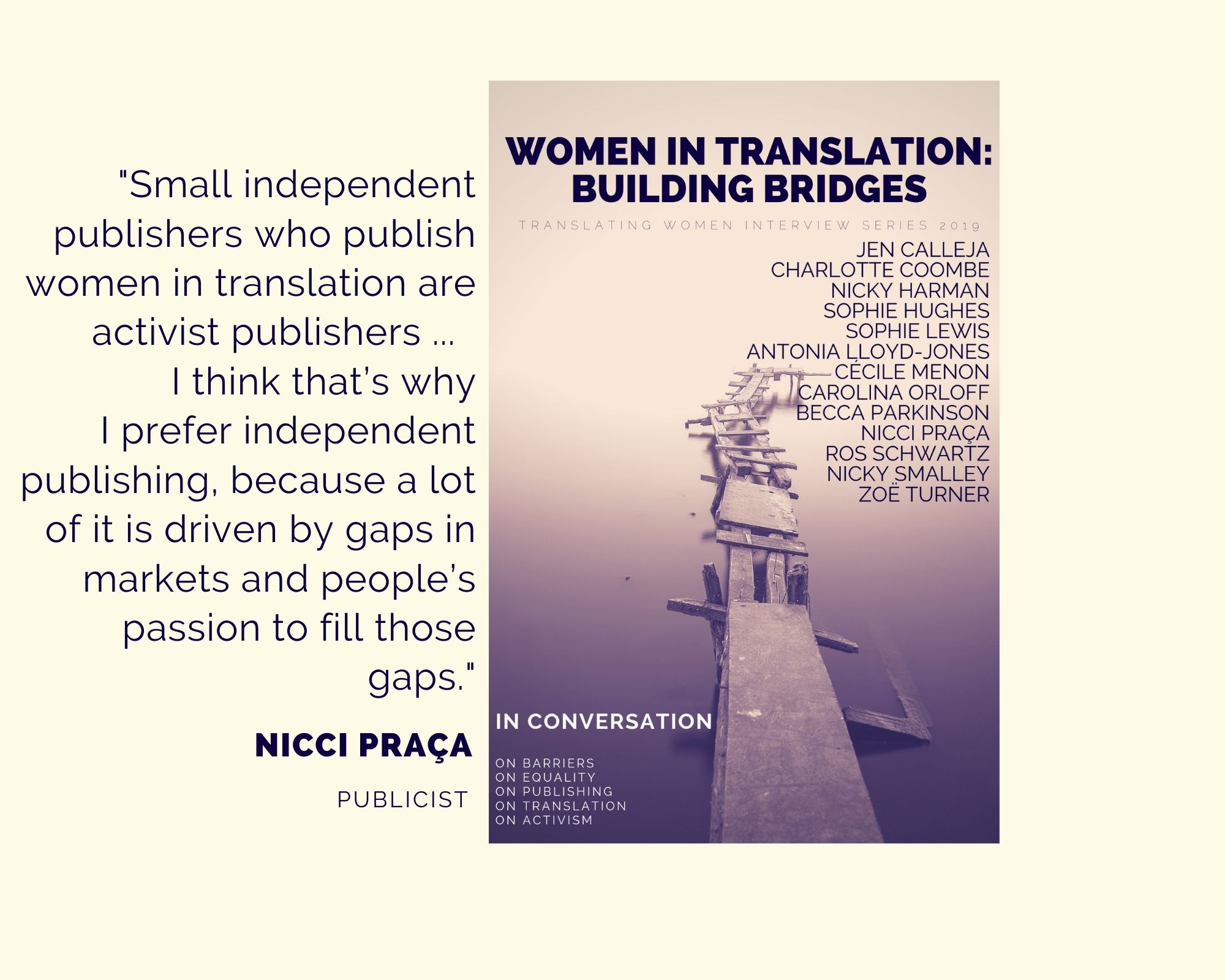

It’s an odd situation because a lot of the translators are women, but the books we’re publishing aren’t necessarily by women writers. The percentages are still very low, which makes small independent publishers who publish women in translation activist publishers. They’re the ones who see that there is a gap in the market which needs to be filled. I think that’s why I prefer independent publishing, because a lot of it is driven by gaps in markets and people’s passion to fill those gaps.

You’ve worked with a number of publishers who have different approaches to translated literature; what activities do they undertake to promote translation and help those works to reach publication?

Obviously publicity around those books and those authors is very important, and every publisher will undertake to make sure that a book gets the right kind of publicity or as much publicity as possible. But the ones who are actively working hard on this are the translators: they do the bulk of the work, talking about writers and pitching them as much as possible to get them in print. A good publisher will take an author and nurture them and continue to publish their work, which is very important, but funding is also very important: if publishers don’t have the funding to pay for a translation a book might not necessarily get published. They work hard at getting the funding for these books, and then submitting them for prizes where possible, but what they can do is fairly limited. The media has more work to do: they have more opportunities, but they are reluctant. Getting a foreign author on the BBC is really difficult. Even if the author has an incredible reputation overseas, it’s still really hard. Part of that is because of language: if they don’t speak English “properly”, there is a reluctance to put them on air, and so writers have to be so extraordinary before someone in the national media will even begin to take a look at them.

That sounds quite stagnant; Christopher MacLehose wrote an article over ten years saying much the same thing: that authors are heavily involved in promoting their own work, and that translators take on a lot of the publicity work. So why do you think it isn’t changing?

Gatekeeping. Gatekeeping is one of my biggest bugbears. It makes things so difficult, because if you’re not getting the publicity for a book, how do you get the word out there? Most sales teams don’t consider online publications to be strong enough mouthpieces to sell books, but as a publicist I disagree with that. I think that online publications are much stronger than radio and newspapers, particularly now, because I’m not sure how many people really trust what’s coming out of certain media platforms. And that’s where the Internet has really helped us, because we can circumvent the national media to get word out there. The Internet has also really helped independent publishers: if they had no platform to inform people of the books that they’re publishing, nobody would know about them and no-one would buy them because it’s also really hard to get books into bookshops. You’ve got another set of gatekeepers there and they only really get on board when they see everybody else getting on board. So the internet is crucial to the publishing industry, certainly in terms of literature in translation.