I recently reviewed Guadalupe Nettel’s new collection, Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories (tr. Suzanne Jill Levine, Seven Stories Press, 2020), and this week am delighted to bring you an interview with Guadalupe herself, offering insights into the themes and inspirations for Bezoar.

All of the stories in Bezoar deal with obsessions – from seemingly innocuous ones to those that can take over a life and set it on a different course. Did you deliberately write with this common theme, or is it a coincidence that there are echoes between the various stories?

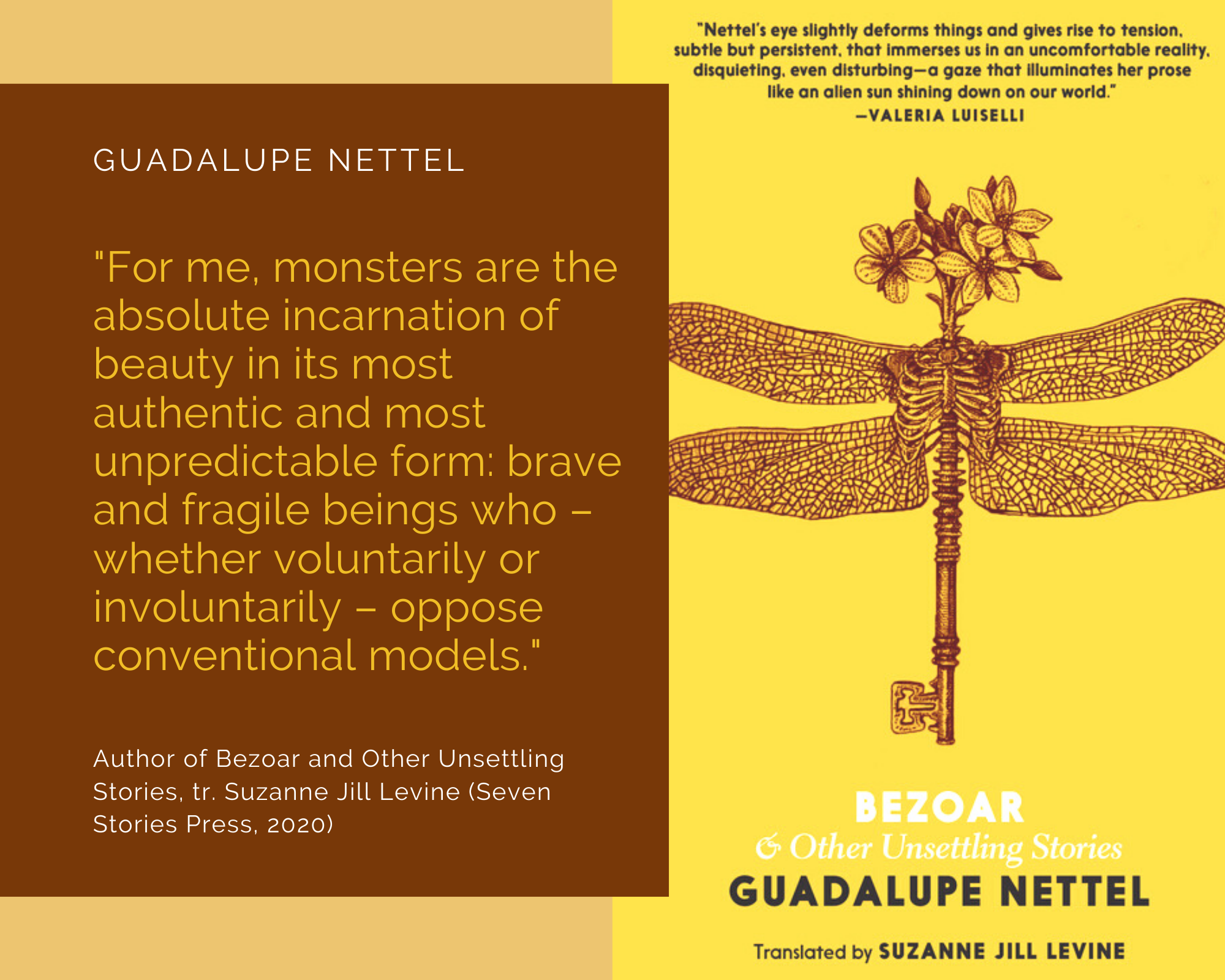

Bezoar is a personal reflection on beauty, the beauty of anomaly. I’ve always felt drawn to uncommon people. For me, monsters are the absolute incarnation of beauty in its most authentic and most unpredictable form: brave and fragile beings who – whether voluntarily or involuntarily – oppose conventional models. But I didn’t choose characters that are completely out of the ordinary. Rather, I wanted to shine a light on compulsions and obsessions, the perverse tics and characteristics of ordinary people, the people we come across every day, ourselves even. We all have some aspect of our personality that we’d like to hide at any cost. As William Shakespeare said: “We renounce what we are to be what we hope to be.” However, I’m convinced that this thing that we try so hard to keep hidden is the source of our true beauty. I’d like it if in reading these stories, people – especially those who find themselves physically or psychologically repulsive and who are constantly comparing themselves to images of beauty and perfection in the media – started to see themselves differently; I’d like it if these stories made them want to embrace the characteristics that make them unique.

Many of your narrators and protagonists are outsiders, whose life and experience is characterised by solitude – desired or enforced – and who exist in some way outside of conventional relationships, experience an estrangement from their own bodies, or inhabit their bodies in uncomfortable ways. What made you want to offer these perspectives in particular?

By the age of twenty I knew that I wanted to write about outsiders; about people who stand out from the crowd because of both their physical and psychological characteristics; about the blindness that is always looming over me, creeping up on me; about madness and things that others don’t tend to want to see. Without a doubt I’m an obsessive woman: I brood over my subjects ad nauseum.

Solitude is a theme that has marked my life. The solitude of the teenager, of the patient, the elderly person, the solitude of grief, of abandoned children, of people who, for one reason or another, live on the margins of society, but also the solitude of the many people who live isolated in big cities, without friends or family. I feel deep empathy for people who experience solitude, whether involuntarily or by choice. At the same time, reading is a powerful way to cope with solitude. Sometimes, when we read the right author for us at the right moment of our lives, even if it’s a Japanese writer from the 12th Century, we can feel identified and understood in a way that even our best friend can’t understand us. Fiction opens our minds, it makes us learn about other societies and cultures, imagine places where we haven’t been and like people that we never imagined we would understand. Not to mention past times or the different futures that humanity could face.

Some of the characters are also voyeurs, though not always in a conventional sense, and their voyeurism is very much connected to the cities they inhabit. Were there real people and/ or places that inspired these characters?

All these characters are inspired by friends, people I know, siblings or even myself. The second story, where a girl is spying on her handsome neighbour from the window while he is trying to get in bed with another girl, was inspired by a Cuban friend who taught me how to be a voyeur in NYC. At the beginning I didn’t understand anything I saw in the window, but he taught me how to decipher it: Do you see that vertical line?” He asked. “It’s a curtain. And that horizontal line on the left? The arm of a guitar. The red circles underneath are a woman’s toenails.” Writing is a kind of voyeurism. You start with snippets you overhear, images you see, and then you complete the story.

Of course the origin of these stories was influenced by the cities in which they were written. Some of them were written in the north-east of Paris. The story that opens the book is set near Place Gambetta. It’s about a photographer who specialises in taking pictures of people’s eyelids. A lot of people have asked me how I managed to come up with such an absurd premise, and my answer is always that this person exists or existed in real life.

“Bezoar”, the title story, was written in Barcelona, where I lived for some years, but I didn’t want the place to be too recognisable and so I mixed it up with memories from a recent trip to Portugal. It was inspired by a particularly obsessive period of my childhood when I used to compulsively pull out my hair.

My three stand-out stories from the collection were “Petals”, “Ptosis” and “Bezoar”, all of which feature men who become obsessed with fragile women they want to save, but who they ultimately fail. Was this a deliberate theme that you wanted to explore?

I think that when I wrote these stories I was coming to terms with something which at that point was fundamental and painful for me: no-one can save another person if that person doesn’t want to be saved, and doesn’t give themselves over to being saved, no matter how much love we give them, no matter how much attention, interest or affection we bestow on them. Everyone has their own way of living, and no-one else can interfere with that. On the other hand, often what we consider to be the “right path” might not be the right path for others. In “Ptosis”, the photographer wants the girl to keep conforming to his ideal of beauty, but all she wants is to be like everyone else. Trying to impose a model of beauty or behaviour on someone is an extremely violent act.

The title story is taken from a myth about a healing gemstone that is also a ball of hair. Why did you choose this image/ legend around which to construct a story, or a collection of stories?

It’s a myth that human beings believed in for centuries, and now we find it completely absurd. There are bezoars in the Met Museum in New York, and I imagine in other museums across the world as well. The fact that a ball of hair can be seen as a precious jewel shows that it’s our own imagination that gives objects their value. But what interests me most about this object is what people want from it: an end to their suffering. What does it matter if it’s only a ball of hair, if this stone can bring peace and heal our illnesses or pains? That’s what we’re all ultimately searching for, and I find that very moving.

“Unsettling” is a superb word to describe these stories – I was expecting something possibly supernatural, but they are unsettling precisely because they are only a hair’s breadth away from common realities. Where do you draw inspiration for these stories, and why is it important for you as a writer to “unsettle” or disturb?

As I said earlier, literature opens our minds, but this doesn’t always happen in a gentle and painless way. When we move away from what’s familiar to us, it’s normal to feel some discomfort. I think that if this book is unsettling, it’s because when we talk about how other people are strange, it’s almost impossible not to think about how we are too. Even readers who thought they were completely “normal” realise that they too, or their loved ones, might be a little monstrous and have been trying to hide it their whole life.

How do you cope writing such unsettling stories in the first person? I’m thinking of what it would take to produce creepy phrases such as “I chose to discover women in the only place where they don’t feel observed: bathroom stalls” – is there a single approach that you take, or does it differ between stories?

It comes naturally. All my characters are outsiders in one way or another. When I was a child, I often felt judged and ashamed because my eyes were “abnormal” – I was born with a congenital cataract and other problems in my right eye – and as a result of seeing with just one eye, I moved and behaved differently to other people. So I identify with the figure of the outsider. I don’t think I could bring a character to life if he or she wasn’t in some way a freak.

Were you involved in the translation process? More generally, how does it feel for your work to travel between languages and cultures?

When I can speak and understand it, it always gives me a bit of a shock to read myself in another language, but I find it amazing. To be translated into other languages and to be read by readers from different countries is an immense privilege.

Translation is an extremely delicate process. If it’s bad or careless it can be very damaging. It’s not like a badly subtitled film where you have not only the words but also the mise-en-scène and the acting, and so you can immediately identify incongruities in the translation. In literature, language is everything! Literary translation has to be one of the most difficult and admirable professions going. If the translation is into a language I understand, like English, I try at least to read the translation and collaborate as much as possible with the translator: answer their questions, deal with any doubts they have, make suggestions and correct potential errors. But I also try to respect their own style and interpretation.

Translation of those sections originally written in Spanish: Helen Vassallo, 2020