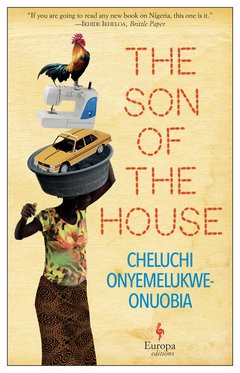

Europa Editions, 2021

First of all, subscribers might have noticed that the blog posts have been coming less frequently lately, and I’m sorry for this. As long-term readers will know from my open letter last year, I had hoped to carry on as normal during the pandemic, despite the added time restrictions that came with balancing work and homeschooling. As the months have gone by and things haven’t eased up, I’ve had to significantly reduce the number of books I read and review. I have my reviews backlog down to four books, so there will be a few in quick succession now and then a break again for part of the summer; I’m grateful for your patience while the posts are less regular.

I hope you’ll enjoy the review I’ve got for you today: it’s a slightly different review than usual, in that the book isn’t a translation. It’s by Nigerian debut author Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia, and is written in English. This actually raised some interesting questions as I was reading it, as there were frequent turns of phrase that stood out to me as a different kind of English than UK English, and this made me fall down a rabbit hole: I asked myself whether if it were a translation it would come under easy fire for not being “authentic” in English, whereas authenticity can be just as much about the source context as the target context. Anyway, I didn’t reach a conclusion on that, but it made me think about how translations are judged in terms of linguistic quality (including by me) and what biases we might bring to it when we talk about “quality”, and so I thought I’d throw it out there so you can join me down the rabbit hole!

The Son of the House follows the lives of two very different women who, for the most part of the narrative, are entirely unaware of what binds them together. Three separate stories unfold: first there is the framing narrative, in the present day, when Nwabulu and Julie find themselves together in a sticky situation. Then as they tell their stories to one another, we are transported back first to Nwabulu’s miserable and abusive childhood, then later her attempts to find autonomy and her love affair with Urenna, the son of a rich family, and the pain and humiliation that relationship ultimately brings her. Next we delve into Julie’s past: she is educated and therefore respected as a professional, but single and therefore not valued as a woman. This state of affairs, and the age she finds herself at, force her to resort to desperate measures in order to marry a man she barely tolerates. Finally, the two back stories come together when the women fall victim to what the blurb for Son of the House describes as “dramatic events straight out of a movie.” I confess this wasn’t a line that pulled me in (I’m not a fan of improbably sensational tales), but the dramatic events referenced were, I thought, entirely believable – the bigger suspension of belief has to come regarding the connection between the two women. I managed not to be too cynical, though, as I reminded myself how often “real life” brings enormous coincidences of people and place, and the coincidence in question is well thought through in terms of narrative development. I don’t think it’s intended to be any significant mystery or revelation, as I guessed it almost instantly (and I am notoriously terrible at guessing correctly when it comes to plot intrigue). So although I still won’t mention the details because NO SPOILERS, I suspect you’ll figure out fairly swiftly what connects the two women, and then you can just enjoy reading about how they each arrived at the point they find themselves when the narrative opens.

The focus on women underlines the many cultural and social restrictions they face in their daily lives, and how these change (or not) in the course of several decades: this focus reflects Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s work as a lawyer working against gendered violence, and shows how social status and wealth can never truly protect women from being reduced to objects and targets. The women are helpless in the face of men’s lies and machinations, and too often other women are complicit in their condemnation, the frustratingly facile phrases “because he is a man” or “because you are (just) a woman” so frequently used to legitimate life-altering injustices. The civil war and its aftermath is an omnipresent backdrop, but cleverly woven into the narrative without any obvious agenda. Similarly, the perilous circumstances in which the women find themselves is not just a narrative device to entangle their fates, but also a comment on the fragility of freedom for women in Nigeria. The Son of the House is an extremely enjoyable novel: it offers intrigue without relying too much on mystery or suspense, and the humanity of “two women doing their best in their world” radiates as much in Nwabulu and Julie’s moments of ignominy as in their moments of glory.