CREATOR/S: Posy Simmonds

YEAR: 1979

PLACE: London

PUBLISHER: Jonathan Cape

ORIGINAL PRICE: £3.95

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? British Library

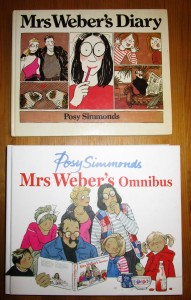

Fig. 1 and fig. 2. Cover and spine of Mrs Weber’s Diary © 1979 Posy Simmonds and Mrs Weber’s Omnibus © 1979, 1981,1982, 1985, 1987, 1993 and 2012 Posy Simmonds

I’m going to take a break from my recent Conan musings to discuss the 1979 book Mrs Weber’s Diary by Posy Simmonds. Simmonds is a comic creator best known for the graphic novels Gemma Bovery and Tamara Drewe. Simmonds’s weekly comic strip in the British Guardian newspaper featured the major themes of those books: contemporary manners, the legacy of the 1960s on middle-class attitudes, and taste and consumption practices as identity-constituting acts. Those strips, which began in May 1977, were reprinted as collected editions (Mrs Weber’s Diary was the first), and the compendious Mrs Weber’s Omnibus (2012) brought them all together under one cover.

Mrs Weber’s Diary works as an integral unit of 58 pages, running from January to December 1978 and from a New Year’s walk to the school Nativity play. It follows the year of Wendy Weber, her husband George, their large family and their friends the Heeps and the Wrights. As the title indicates, the comics are interrupted and framed by Wendy’s diary entries. Simmonds’s eye for the detail of middle-class mores and rituals includes the brief note in December’s diary:

TV Times

Radio “

The piles of Radio Times and TV Times in newsagents and supermarkets, even in today’s age of the internet, is a reminder of the habit of buying TV guides over Christmas to allow one to plan one’s viewing over the festive season. UK readers of a certain age will remember the time when, to get complete coverage of the schedules, one had to buy the Radio Times and the TV Times to cover independent broadcasters and the BBC respectively. Details like this in Wendy Weber’s diary show her fidelity to this annual ritual.

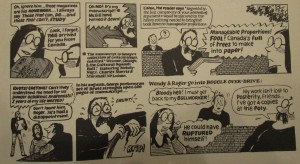

For me the star of the book is George. A Senior Lecturer in Liberal Studies, George is able to transform everyday life into the subject of academic discourse, and if his books The Meta-Megalith: A Structuralist Interpretation of the Career of Buckminster Fuller and Weimar, Chicago, & the Cultural Squash Ball do not currently exist, it is only a matter of time. George’s passion for his own research rises to heroic heights when rebuffed; when McGill turns down his collection of essays on the grounds of length (600 pages) the enraged George tears his manuscript in half (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Detail from Mrs Weber’s Diary © 1979 Posy Simmonds

Wendy, hoping to wind him up, replaces the flower-pattern blind in the kitchen with a Toile de Jouy print full of bucolic scenes. George does not recoil from the kitsch; he is inspired to launch into a rhapsodic celebration of the pattern as a “TRANSPLANAR cultural model… the mediator between NATURE outside & CULTURE inside!” Even the characters in the pattern protest at having to listen to George’s intellectualizing – but it’s the source of amusement to the reader. Simmonds’s depiction of George, a former radical maintaining a semblance of his 1960s politics while fulfilling the demands of work and family, was influenced by her time as a student at art school in the 1960s (see Sabin). Simmonds’s careful delineation of her characters’ peccadilloes is well judged: because there are so many references to George’s interest in structuralism, readers familiar with this body of thought can see why he would be so enthused. The old New Leftist is not shocked by the pattern, he loves it: he sees in it confirmation of his structuralist model of a world divided into nature and culture, whereby the liminal state of the window over the sink (dividing private and public space) is acknowledged as a porous membrane with images of premodern agrarian life passing into modern Enlightenment. Haberdashery recapitulates phylogeny.

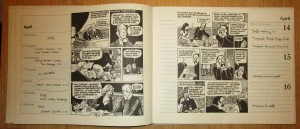

The figure of the lecherous, predatory professor, an enduring stereotype in popular culture, casts a shadow over Mrs Weber’s Diary, although Simmonds doesn’t reduce George to this stereotype. In the month of April in the book the diaries of Stanhope Wright (an advertising director) and George are juxtaposed (see fig. 4) on facing pages.

Fig. 4. Pages from Mrs Weber’s Diary © 1979 Posy Simmonds

Set within the pages of each diary is a comic detailing a similar encounter: an older man spends an evening with a younger woman over whom he has authority in the workplace, an encounter taking place because the man has lied to his wife that he needs to stay late at work. Stanhope is dining with his secretary Carol at an expensive restaurant, but his seduction is rebuffed; she needs to get back to her mother, and Stanhope thinks “Excuses Excuses!” George is out drinking with one of his students, who plies him with drink, but at the end of the night George declines to leave with her. This does not appear to be because of a moral opposition to infidelity, since George tells her that the Webers have an open marriage. He can’t afford to spare the time. He needs to get home because the boiler is faulty and if nothing is done the guinea pigs could be “overcome with fumes”! George is positioned as the frustrating party, and the student thinks “Excuses Excuses!” George is the butt of the joke, but not because he is a failed lothario; these paired scenes construct him as a verbose buffoon in the same position as Carol the secretary (not least where composition of the final panels of each page is concerned), protesting that familial, domestic demands compel him to return at once. Here George is a deflated, homely version of the far more sinister, promiscuous academic Howard Kirk in Malcolm Bradbury’s 1975 novel The History Man.

Whether he is analysing his friend’s ponytail, or a painting used to promote whisky, or his own status as a father on a bus, George continually brings sociological and semiological interpretations to his everyday life. He is a Cultural Studies pioneer in that respect. Yet George gets partly lost in his reveries, and in this he may represent a warning that obsessive academic interests are solipsistic and narcissistic. Unable to stop himself slotting phenomena into the methodologies and theories of his research, one could potentially read George as a marker of the slow slide in which doing work has infiltrated the unpaid leisure time of workers in academia. George is so alienated he holds his personal life at one remove while he analyses it, turning his own experiences and lifeworld into material on which his skills can be practiced.

While that reading chimes with the jaded lecturer in me, there’s a joy in George’s compulsive need to analyse the occurrences and objects that populate his life. He manages to even amuse himself through the incongruity of his high theorizing and unlikely subject matter. In an underwear shop he muses “the SYNTAGMATIC ORDER of bra, suspender belt & knickers, could be understood as the FOUNDATIONS OF STRUCTURALISM…Ha Ha!” He knows the ridiculousness of his thought experiments and enjoys them, he is able to play with intellectual possibilities, and in doing so he can endure what, certainly in the underwear shop, are the demoralising effects of consumer culture. George’s intellectualizing is a way of putting up with and understanding his life and not an escape into some passive interiority. Because of it, the world of family and work and shopping is continually fascinating, endlessly rewarding.

November 2015

Bibliography

Sabin, Roger. “Some ‘Contemptible’ British Students.” The Education of a Comics Artist: Visual Narrative in Cartoons, Graphic Novels, and Beyond. Ed. Michael Dooley and Steven Heller. New York: Allworth, 2005. 214-20. Print.