Home » Articles posted by Site Admin

Author Archives: Site Admin

A reflection and a warning – Universal Support

Universal Support.

Christos Kotsogiannis, Professor of Economics, University of Exeter, and Director of the Tax Administration Research Centre (TARC).

March 26, 2020

Who would expect this three months ago? Certainly, we did not even know that such virus existed! Now the world is facing an ‘invisible enemy’ which has (putting the health crisis and the immediate need to respond to this aside!) disrupted economies and society on the scale that most of us have never witnessed, seeking ways to fight against it. Many countries have taken extraordinary fiscal and monetary policy measures, announcing a plethora of unprecedented fiscal stimulus packages to smooth out consumers’ income and stimulate demand and limit the human and economic impact of COVID-19.

Already significant global production has been lost, and the forecasts for growth are being continuously revised, downwards, as events further develop.No matter how optimistic one is, the current pandemic crisis will inevitably lead to a deep economic crisis with long lasting impact (than the economic crisis of 2008). The sheer magnitude of the pandemic shock makes forecasting incredibly complex. The extent of the lost production will of course depend on how severe and persistent the pandemic is, as well as the measures countries adopt individually and collectively. Stimulating demand, as desirable as it is, will not be enough as the global supply chain is also disrupted (even if consumers’ purchasing power does not change, demand cannot be fulfilled if the global supply side is severely affected by the necessary lockdown).

A crisis of this magnitude requires bold actions. A combination of direct transfers to consumers and support (direct and indirect including deferral of payment of tax liabilities) to businesses is likely to be an effective policy – but getting the mix right for the latter is challenging and will depend on administrative capacity. Delivering brand new administrative systems to administer complex policies is hard, as is to set income and profits thresholds for which assistance policies may depend upon. How much and how quickly resources can get to households and business is therefore a pressing issue. If financial support is difficult to deliver in a timely fashion universal support is the right instrument, even though some ‘non-deserving’ businesses might benefit from them too.

The pandemic is affecting supply, and productivity, of the economy and as such will make business investment more costly. A change also in the way we do things is required. Social-distancing and lockdown policies mean working from home, for those sectors that can. But working from home has its own limitations, and adjusting to this is not only challenging but takes also considerable time. If aggressive demand-boosting policies are not adopted, the incentive of business to invest will be reduced further fuelling a loss in productivity which in turn will fuel even less demand. If not acting decisively, there is a danger that economies will find themselves locked in a ‘low-economic-growth-trap’.

Importantly, to win the ‘war’ against the ‘invisible enemy’ global coordination is needed, as the pandemic is affecting the global economic network. Though there are good signs of this happening already, more needs to be done. We live in unprecedented times, but this is the time where the global community should realise that it is better to coordinate than to compete. This, inevitably might help the global community in solving another big challenge it faces, for example, climate change. When normality resumes, the pandemic experience should make climate change coordination easier to achieve. While the 2008 crisis was more of a crisis of institutions the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is not. Importantly, the ‘shock’ is symmetric and affects all countries. But how successfully a country deals with the pandemic will depend upon how quickly the institutions have been mobilised. This realisation, and the successful conclusion of the pandemic, can act as a ‘coordination device’ where we consumers, producers, states and international organizations coordinate on a good equilibrium following the social norms consistent with the common good. This might take time but there is hope that for a much better world after we get through this.

Regulating Financial Technology – Professor Alison Harcourt

Originally appeared in Risk and Regulation: http://www.lse.ac.uk/accounting/assets/CARR/documents/R-R/2019-Summer/190701-riskregulation-05.pdf

Financial technology (FinTech) is greatly changing the way in which citizens live and work on a day to day basis. Fintech refers to technological solutions for electronic transactions such as blockchains, cryptochains, digital currencies and peer-to-peer online lending. The introduction of cryptocurrencies around the globe, such as Altcoin, Bitcoin, LiteCoin, PeerCoin and Ripple, and the adoption of national e-currencies, such as the Bank of England’s RSCoin and the M-Pesa in Kenya, are accelerating FinTech use. The growth in mobile phone use, interfaces such as Alexa and Google Home Fiber Voice and social media platforms ease the payment of online goods and services.

As the world moves towards paperless money and online transactions, London has established itself as a world hub for FinTech. The UK’s FinTech was worth £6.6 billion with an annual growth rate of 22 per cent between 2014 and 2016 accord – ing to HM Treasury (2018). The greatest bulk of this income is from cryptocurrency transactions and peer-to-peer lending. UK Trade & Investment (UKTI) estimates the highest growth to be in ‘peer-to-peer lending, online payments and the data and analytics products (credit reference, capital markets and insurance)’ which represent 60 per cent of the market. In its 2018 FinTech strategy, the UK Treasury stated ‘the UK market is one of the most attractive markets in Europe based on our analysis of market opportunity, availability of capital and regulatory environment’. With more people working in Fintech in the UK than in New York, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan combined, the UK market has become an important part of the global economy. In face of these developments, regulatory responses have invariably been characterized as a game of catch-up. At the same time, regulatory responses have also been strategic, involving processes both of regulatory competition and cooperation.

The overall regulatory goal has been to encourage solutions and new market players to FinTech with the support of government measures. The UK has been particularly proactive. This began in the UK when the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) was looking for innovative ways to move the UK out of the financial crisis and at the same time to reform and regulate a changing financial sector. The FCA established Project Innovate, ‘regulatory sandboxes’ and its FinTech Initiative. The sandbox schemes waived a series of FCA rules for a small number of FinTech start-ups. This was to create a ‘safe space’ for company innovation where companies could test new goods, services and delivery mechanisms. The idea was not new but was based on ‘Innovation Deals’, such as the Green Deal programme of the Netherlands. Such programmes ‘do not support “normal” business activities, but would be restricted to innovative initiatives that have only a recent and limited or even no access to the market with the potential of wide applicability’ (European Commission, 2016).

The first FCA sandbox in 2016 fostered 24 companies.1 By 2018, it had reached its fourth cohort with 29 companies. 2 This attracted new start-ups to the UK such as SETL which worked in the retail sector as the first company to use a digital ledger. At the time of writing, the FCA was running ‘Tech Sprints’, assist – ing companies to innovate on the regulatory front. In 2018, the FCA was also running Innovate Finance events in conjunction with the Treasury and the Department of International Trade.

The UK sandboxes triggered interest from the European Com – mission and states around Europe. FinTech sandboxes have begun to emerge in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands and Sweden. Globally, this was followed by regulatory sand – boxes being set up in Hong Kong, Australia and Singapore.

Other UK-led initiatives have since been noted such as the relaxation and introduction of flexible rules for selected new market entrants and the introduction of self-regulatory trust schemes. These include FinTech developments by the US Federal Reserve Board, US Treasury and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the incoming US financial law which raises the Dodd-Frank threshold from $50 billion to $250 billion for smaller enterprises and eases restrictions for FinTech (Thomas, 2018). Trust schemes include the European Union’s eIDAS Regulation on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market which came into effect in 2016. In the US, regulatory guidance has accompanied the legality of cryptocurrencies via the Financial Crimes Enforcement (FinCEN) agency and the Internal Revenue Service requirement that intermediaries have to clear with them prior to establishment (IRS, 2018).

In the UK, FinTech was also seized upon for the establishment of new trade relations. Cross national cooperation with the FCA involved, for example, setting up RegTech partnerships with Australia and Singapore in 2017. In 2018, FinTech was a key highlight of UK trade negotiations with India where the two partners aimed to ‘deepen bilateral collaboration on Fin – Tech and explore the possibility of a regulatory cooperation agreement’ (Joint statement UK-India, 2017) including the establishment of a ‘FinTech Bridge’ between respective regulatory authorities. Indian and African states are of particular interest to the UK given the growth in FinTech. Citizens, particularly in rural areas, have limited access to banks and normally financial transactions are done via post offices and other local intermediaries which incur time and fees (World Bank, 2017). Mobile phones are rapidly alleviating this problem with applications and online bank accounts which increase financial inclusion of citizens in the economy.

FinTech presents many advantages particularly as it substantially lowers the cost for transactions in comparison to fiat money. However, the pace of technological change also presents many challenges. Financial services have for decades been operated by established incumbents (banks and intermediaries) with cultures that often slowed technological adoption and barred entry for new operators. Similarly, technological solutions are developed by the largest tech companies worldwide presenting problems of market concentration, customer lock in and lack of interoperability. Lastly, the need for customer authentication often requires technologies such as device fingerprinting, voice and facial recognition as well as biometric data which is increasingly used to authenticate identity. For example, India has introduced the AADHAR card which has registered biometric data (including iris scans and thumb prints) of over 1.2 billion people. The creation of huge databases presents not only vast opportunities for FinTech on many fronts but also challenges to security and privacy. International payments also encounter cross-border problems of data localization and passporting.

The UK however is clearly acting as policy entrepreneur in steering the future trajectory of FinTech development and how this game at regulatory competition will eventually develop, what trajectories will become critical, and how regulators will be positioning themselves in FinTech represents one of the key regulation research agendas over the coming years.

1 Billion, BitX, Blink Innovation Limited, Bud, Citizens Ad – vice, Epephyte, Govcoin Limited, HSBC, Issufy, Lloyds Banking Group, Nextday Property Limited, Nivaura, Otono – mos, Oval, SETL, Tradle, Tramonex and Swave.

2 BlockEx, Capexmove, Chasing Returns, Community First Credit Union, Creativity Software, CreditSCRIPT, Dashly, Ehterisc, Finequia, Fractal, Globacap, Hub85, London Me – dia Exchange, Mettle, Mortgage Kart, Multiply, Natwest, NorthRow, Pluto, Salary Finance, TokenMarket, Tokencard, Universal Tokens, Veridu Labs, World Reserve Trust, Zip – pen, 1825, 20|30.

REFERENCES

Arner, D.W., Barberis, J. and Buckey, R.P. (2017) ‘FinTech, RegTech, and the reconceptualization of Financial Regulation’, Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business 37 (3) (Summer 2017): 371–413.

European Commission (2016) ‘Better regulations for innovation-driven investment at EU level’, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. https://publications.europa.eu/ en/publication-detail/-/publication/404b82db-d08b-11e5-a4 b5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-79728021 (Accessed 24 May 2019).

HM Treasury (2018) Fintech sector strategy: securing the future of UK Fintech. https://assets.publishing.service.gov. uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/692874/Fintech_Sector_Strategy_print.pdf (Accessed 21 March 2019).

Internal Revenue Services (2018) Internal Revenue Bulletin. Notice 2014-21. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-14-21.pdf (Accessed 21 March 2019).

Joint statement by the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Finance Minister of India at the 9th UK-India Economic and Financial Dialogue, Delhi, 4 April 2017.

Thomas, L.G. (2018) ‘The case for a federal regulatory sandbox for Fintech companies’, North Carolina Banking Institute 22: 257–82.

Farmer-centred innovation and knowledge exchange at the ESEE 2019

Beth Dooley is a second-year PhD student with the Centre for Rural Policy Research in the Sociology, Philosophy, and Anthropology Department. She received the Rowan Johnstone PhD Studentship to explore the myriad complexities involved with building resilience in UK agricultural policy.

Thanks to funding from the Centre for European Governance, I had the privilege of attending the 24th European Seminar on Extension (and) Education, or the ESEE 2019, from the 18-21 June 2019 in Acireale, Italy, positioned along the eastern coast north of the city of Catania, Sicily. As an agricultural lawyer specialising in farm succession planning, rural development, sustainable agriculture and mediation, I’m now broadening my skill set to include farmer learning and knowledge exchange as a rural sociologist by undertaking a PhD at the University of Exeter. Therefore, this conference was incredibly important to attend as the hub for the leading academics and practitioners working on agricultural knowledge exchange and innovation processes to highlight advances in research, practical implementation experiences, outcomes, benefits, challenges and next steps. Conference delegates came from all over Europe and beyond (Iran, New Zealand, US, etc.) to engage with issues around innovation throughout agriculture and the policy and governance structures that enable those processes to flourish. Key questions explored throughout the conference that I need to critically engage with for my PhD research and beyond in this field are the role of facilitation, farmer learning evaluation, complex decision making skills and capacity development, and how programmes, projects and initiatives value the targeted stakeholders’ input in designing the intervention meant to contribute to some type of change and learning, as well as how they facilitate the design of innovation support services to incorporate that approach.

The opening keynote address ‘Transformation, Disruption and Plurality in Agrifood Systems: Emerging Directions for Research on Extension’ was delivered by Dr. Laurens Klerkx of Wageningen University, challenging the delegation to think critically about future questions to explore how we understand and facilitate agricultural knowledge exchange and innovation processes.

Amongst many incredibly important areas identified in relation to policy and governance frameworks, he pointed to the inherent contradiction between the push for co-creation in agricultural research for innovation and the way current funding structures work. Co-creation involves research design, implementation and development of outputs through a process of engagement between on-the-ground stakeholders, researchers, advisors, etc. around topics that farmers find useful, relevant and necessary rather than a top-down decision from the researcher(s). As it is iterative and intended to foster innovation as well, what will come out of the process is unknown at the start, whereas funders typically require up-front expected deliverables. A change in funding approaches is needed to allow for the autonomy necessary to let this process happen, but it will hinge on policy makers understanding and trusting the process and will likely require the development of new ways to measure, quantify and evaluate impacts to justify expenditure from a public management standpoint.

Multiple breakout sessions were conducted over the four days, highlighting research and projects contributing to four different themes: 1) Education and Extension: roles, functions and tools for boosting interactive approaches to innovation, 2) New skills and capabilities for Extension to achieve innovation policies objectives, 3) Enabling policies for R&I: governance, frameworks and pathways, and 4) The changing role of monitoring and evaluation: approaches, methods and instruments. One of the projects funded under the Horizon 2020 research programme of the European Commission that presented a lot of findings was the AgriDemo project. Researchers talked about the key characteristics and best practical approaches for organising effective on-farm demonstrations identified through the project and how networks amongst the demonstration farms could operate as a support tool for learning. This work is relevant to my PhD research as I work on peer-to-peer learning and farmer engagement within group knowledge exchange events, more particularly farmer discussion groups. I’m conducting participant observation of seven groups over the course of nine months to a year and analysing the data through the lens of social learning theory as understood from an educational psychology point of view in addition to the work around communities of practice, both as applied to farmers and beyond. Thus, the findings not just around how to most effectively structure a public knowledge exchange event to promote farmer interaction and learning that may contribute to practice shifts, but also the limitations of current monitoring and evaluation methods in terms of measuring whether and to what extent learning happened for the participants were very instructive.

The H2020 project LIAISON (Better Rural Innovation: Linking Actors, Instruments and Policies through Networks) also presented its initial conceptual framework now at the start in gathering case study examples throughout Europe of rural innovation in an attempt to identify key characteristics that could be applied to help speed up innovation in other projects and networks. I provide research assistance to the LIAISON project as the University of Exeter is a partner in the 17-member consortium spread across Europe. We are currently in the stage of the project where we are identifying interactive innovation projects and conducting desk-based reviews of their project setup as well as interviews with a project representative to dig deeper into

how the project was specifically designed and implemented utilising participatory approaches with various stakeholders to foster innovation in farm management and/or wider rural innovation. Based on this work where 200 projects across Europe will be profiled in the ‘light-touch review’, a smaller number of projects will be selected on which to conduct in-depth analyses of the core elements that were particularly important in promoting the innovation they fostered and how those elements could be applicable across other projects, regions and objectives to speed up innovation processes.

how the project was specifically designed and implemented utilising participatory approaches with various stakeholders to foster innovation in farm management and/or wider rural innovation. Based on this work where 200 projects across Europe will be profiled in the ‘light-touch review’, a smaller number of projects will be selected on which to conduct in-depth analyses of the core elements that were particularly important in promoting the innovation they fostered and how those elements could be applicable across other projects, regions and objectives to speed up innovation processes.

Finally, I was a co-organiser of the workshop session on ‘Evaluating farmer centred innovation: methodologies and evidence to capture multiple outcomes’, which we ran in the world café style to draw out opportunities, challenges and examples of methods from the session attendees. It targeted the 4th theme mentioned above – The changing role of monitoring and evaluation: approaches, methods and instruments – in relation to farmer-centred innovation as an increasingly popular approach to structuring agricultural interventions, but about which there are critical debates regarding how impact has been or could be demonstrated. This relates again to the issue presented above about funding and the evidence-based results required to justify public investment, but the current evaluation methods are criticised in terms of attributing causation to the intervention when many factors may have played a role in leading to change and thereby overstating impacts. The verifiability and rigorous assessment issues around learning and impact are particularly relevant to my work on farmer discussion group participation in relation to complex decision making and business strategic planning and management for resilience, as farmer knowledge and change in management practices have been monitored and measured, but questions arise as to what indicators could potentially be used in demonstrating capacity development and empowerment. The workshop highlighted many challenges and concerns from a quantitative comparability standpoint (e.g., lack of randomised control trials in measuring the learning process), but the participants also collaboratively brainstormed around possible combinations of evaluation methods that would allow for more in-depth understanding of participants’ internal developments and change through the learning process.

New Project on the Prevalence of Public Support for Conspiracy Theories in Europe

Dr Florian Stoeckel, Lecturer in Politics, University of Exeter

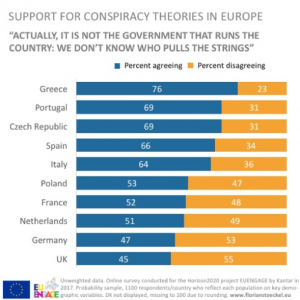

In this new project, we measure the prevalence of conspiratorial thinking in Europe. We also seek to better understand the reasons why citizens believe in conspiracy theories. Joelle Tasker (Exeter BSc student graduating July 2019) and I conduct this analysis based on a novel large-N public opinion survey. The survey was conducted by Kantar Public online. It includes data on conspiratorial thinking in a diverse set of ten European Union (EU) member states and a representative set of about 1100 respondents per country.[1]

Conspiracy theories are usually country specific: for instance, a prominent conspiracy theory in the US is that the September 11 attacks in 2001 were an “inside job” by the US government. A popular conspiracy theory in Poland is about a plane crash in which Lech Kaczyński died. He was president of Poland at the time. One of the conspiracy theories about the crash describes it as an orchestrated assassination. The official investigation identifies errors of the pilots in bad weather as reason for the accident. In our project, we want to make comparisons across countries. Therefore, we use measures that gauge the extent to which citizens believe in political conspiracies more generally, rather than the extent to which they believe a country specific conspiracy theory.

One of our measures for conspiratorial thinking is the extent to which respondents agree with the following statement: “Actually, it is not the government that runs the country: we don’t know who pulls the strings”. We use an individual’s agreement with the statement as one indicator for the presence of conspiratorial thinking. Our preliminary findings reveal much variation between the ten countries in our sample: agreement with this statement ranges from 45 percent in the UK to 76 percent in Greece.

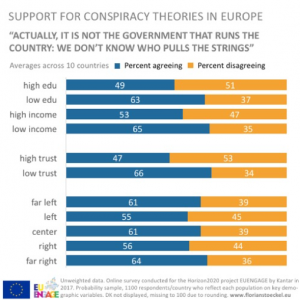

We are also interested in the factors that make it more or less likely for individuals to believe conspiracy theories. Based on a rich literature that examines conspiratorial thinking in the US (e.g. Uscinski and Parent, 2014; Oliver and Wood 2014, Goertzel, 1994), we expect three factors in particular to help us understand who exhibits conspiratorial thinking in Europe. This includes the level of control that individuals perceive to have over their lives, predispositions, and situational triggers. When citizens experience little control over their own lives, they are also more likely to assume that they cannot affect politics either. A conspiracy theory offers a way to rationalise this attitude: it is impossible to affect politics because “we don’t know who pulls the strings” anyway. Experiencing little control over one’s life can be a result of limited material resources, e.g. having a lower income or being involuntarily unemployed. Education, on the other hand, is a cognitive resource which can make it easier for individuals not to feel lost or powerless in a complex political world.

Our survey data support the important role of material circumstances and cognitive resources. On average, the share of respondents who exhibit conspiratorial thinking measured with the above-mentioned survey item is 65 percent among respondents with lower incomes[2] and it is 53 percent among those with higher incomes. The pattern is similar when it comes to cognitive resources. The share of respondents who show conspiratorial thinking among those who did not attend university is 63 percent, but it is only 49 percent among those with the highest levels of education in our sample.

The literature highlights the important role of predispositions for conspiratorial thinking (e.g. Goertzel, 1994; Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig, and Gregory, 1999). We focus on two predispositions: trust and ideological orientations. We are interested in trust as the perception of the world as either a place where one can generally trust other people or a place where one should rather not trust other people. Voters might apply this conception of the world to the realm of politics: citizens who see the world as a place where one can trust other people might be less inclined to think that actors who are unknown to the public are “pulling the strings.” Our preliminary results support this notion. Among individuals who tend not to

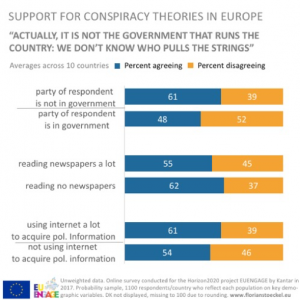

An argument from the US context is that conspiratorial thinking is not only a result of characteristics of an individual but that it is also driven by contextual factors. For instance, it makes a difference for voters whether the party they support is in government (Uscinski and Parent, 2014). Voters are less likely to believe in covert agency when their own party is running the country. We find support for this dynamic also in Europe. The share of individuals who say that “we don’t know who pulls the strings” is 48 percent among those whose own party was in government at the time of the survey. The share of respondents who agree with this statement is 61 percent among those respondents whose party was not in government.

Finally, media consumption can be related to the extent to which respondents believe conspiracy theories. We analyse the role of newspaper consumption and news consumption online. We find stark differences: individuals who read newspapers a lot are much less likely to engage in conspiratorial thinking than those who do not read newspapers at all. In contrast, individuals who get their news frequently from online sources are more likely to engage in conspiratorial thinking than those who do not rely on the internet for political news.

trust other people, 66 percent agree with the statement “that it is not the government that runs the country: we don’t know who pulls the strings”. Among respondents who tend to trust other people, the share of individuals who agree with the statement is only 47 percent.

We also examine if left-right ideology is related to conspiratorial thinking, which is an issue that is being discussed vividly in the research literature (e.g. Uscinski and Parent, 2014; van Prooijen, Krouwel, and Pollet, 2015). Our measure for left-right ideology in this analysis is a general left-right self-placement question which does not differentiate between economic issues and cultural issues. We find that the share of individuals who engage in conspiratorial thinking is lowest among those who take a moderate left leaning position or a moderate right leaning position. Conspiratorial thinking is more widespread among individuals who locate themselves at the centre of the left-right dimension, among those with extreme left leaning positions, and it is most prevalent among individuals with extreme right leaning positions.

In sum, we find that conspiratorial thinking is widespread in Europe. The factors that have been identified in an American context also matter in Europe: resources, predispositions, and situational triggers help us to understand the differences between citizens who show conspiratorial thinking and those who do not show conspiratorial thinking. The next step of our analysis includes the development of a more fine-grained instrument to measure conspiratorial thinking and a multivariate analysis of the correlates of conspiratorial thinking.

[1] A household income of 30.000 Euros or less before taxes.

[2] One of the few other comprehensive surveys with a focus on Europe was conducted as part of the project CRASSH at the University of Cambridge. Results can be found here.

Piercing the Internet’s veil under the New Deal (Dr Joasia Luzak, University of Exeter)

With its announcement of the New Deal for consumers in April 2018, the European Commission gave itself a tall order. At one point of time, the Roosevelt’s New Deal revolutionised the American economy, thus the joint name of the new proposals in European consumer law sounded promising.

Among the main objectives of these two proposals is strengthening of consumers’ rights online. The Commission aims to achieve it by focusing on ensuring more transparency in two aspects: on online markets and with regards to online search results. In this blog post, a question will be posed whether the proposed measures would actually manage to increase transparency on online markets (leaving the issue of online search results aside)?

The transparency that seems to be missing on online markets revolves around the uncertainty as to who is the other party in a transaction concluded online by consumers. It could either be another consumer or a professional party and there could be a third party involved, an online platform, whose status in the transaction may be uncertain, as well. If an online platform is just an intermediary, the contract is concluded between a party offering their goods or services through the platform and a consumer. Whether the consumer-buyer may enjoy consumer rights depends on whether the party offering their goods/services on a platform is a professional party. In any case, there may also be certain duties that an online platform has to meet towards consumers. Thus, to achieve online market transparency it needs to be clear:

- Who is the contractual party of the consumer and is it a professional party?

- Do consumer-buyers enjoy consumer protection?

- Who is responsible for provision of which consumer rights?

So far, especially the answer to the question, whether the counterparty of an online consumer in a transaction concluded through an online platform was a professional party, was not easy to obtain. In a Communication 356 final from 2016 year on collaborative economy the Commission indicated that some of the factors that would have to be considered when determining the party’s professional status were:

- The frequency of providing goods/services (the more often this happened, the more likely the party was a professional);

- The intent to profit (which would exclude such transactions as swapping houses for holidays or reselling ticket sat face value prices);

- The turnover level (from a particular type of activity).

Further factors that should be considered in this assessment were identified by the Court of Justice of the EU in the judgmentKamenova (C-105/17). Ms Kamenova published eight adverts for sale of products on an online Bulgarian platform olx.blg. One of the adverts offered a watch for sale. Unfortunately, a consumer, who has purchased this watch was disappointed with the result, believing that the watch did not meet the product description in the advertisement. Ms Kamenova refused the return of the watch or its replacement. Consumer complained about this transaction and as a result of this complaint consumer authorities in Bulgaria determined that Ms Kamenova was in breach of a series of information obligations towards this consumer. These information obligations followed from the Bulgarian implementation of the Consumer Rights Directive. The Bulgarian court presiding over the case asked the CJEU whether indeed Ms Kamenova could be seen as a professional trader and, therefore, had these information obligations. The CJEU prescribed the evaluation of a professional character of a trader that would account for:

- The organised character of the sale (possibly this could also pertain to the sales’ frequency);

- The intent to profit;

- The information asymmetry between the parties (did the trader have more information than the consumer about the sale?);

- The registered character of the commercial activity of the seller;

- The fact whether the seller pays VAT;

- A position of a seller as an intermediary, and whether he was remunerated for his services;

- The purchase of the goods with an intent to resell;

- Limited quantity of the offer.

As we can see then, there is a list of factors, which list is also non-exhaustive, which will need to be evaluated in order to assess the professional character of the seller. It is not then easy for an average consumer going online to have clarity as to who is contractual party is. The Commission thought to change this state of affairs and drafted a new Article 6a that would be added to the Consumer Rights Directive. This week the text of the Commission’s proposal has been agreed on by the Council and will be analysed below,together with a new Recital 27, on whether it could ensure more online transparency.

When consumers would be concluding a contract on an online commercial platform, they would need to be informed whether the third party offering goods/services was a professional trader. In general, this disclosure should then inform consumers as to whether they can expect to be granted their consumer rights in this online transaction. The problem with the drafted provision is that it allows online platforms to rely on statements made to it by online traders, without having to verify them. On the one hand, it could be, and has been, claimed that online platforms would not have resources to verify whether a party presenting themselves as a consumer is not a hidden trader and tries to avoid having to comply with consumer protection rules. On the other hand, can we really expect consumer enforcement authorities to have more resources than online platforms do? As it will then be left to the enforcement authorities to ensure that there is some compliance sweep through online platforms controlling the veracity of suchstatements.

Further, the new provision requires consumers to be more explicitly and more transparently informed whether their consumer rights are applicable to the contract. More transparent disclosure means that such information cannot be hidden amongst other standard terms and conditions of the contract. Again, this provision could be beneficial to consumers, but the European policymakers do not cross their t’s. Namely, Recital 27 states that it is not necessary to enumerate/list these consumer rights that consumers may enjoy. A lot of consumers will hear a bell ringing then, but not know, to which church to go.

Consumers concluding contracts through online platforms should also receive information, which traders is responsible for granting them consumer rights – the online platform or the seller using it to offer his goods/services. Unfortunately, the proposal does not harmonise, which party should bear this responsibility and to what extent. To the contrary, it leaves it to the contractual agreements between the online platform and the seller to decide, who will be responsible, for which consumer rights. This means that consumers are likely not to have clarity, to which party and in which concluded online contract to go to with their specific claims.

Overall, the identified gaps and inconsistencies do not bode well for ensuring more transparency on online markets. But what can we expect from a proposal that sees as a solution imposing an obligation on traders to provide more information to consumers, when it has already been claimed many, many times that information obligations miss their mark.

Recent Comments