The fundamental premise of our collaborative project is our proposal that if we develop our relationships with matter, with materials, so that they become closer to us, become us and are seen as a part of us, then we will care for, and feel responsible for, their journey in and through the biosphere. Feminist ethics of care foreground close and caring relationships. Deepening our understanding and practice of the various ideas in this strand of thinking seems an important step in our collaboration.

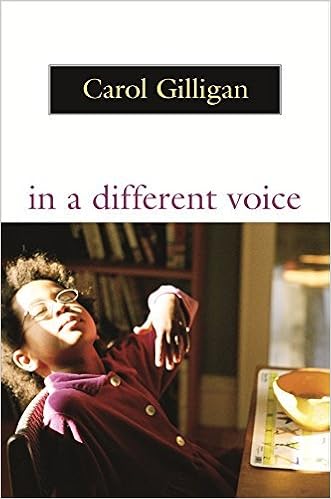

In this blog we will explore the ideas of Carol Gilligan, a landmark feminist thinker, who drew on her personal and professional experiences, (commencing in the 1980s) to argue that ethics and care-taking can emerge in and through our relationships and interactions with others rather than by reference to abstract principles applied universally. To put this another way, universal abstract principles take a principles such as ‘x is wrong’ and apply this to different situations. A relational approach argues instead that the appropriate ethical response arises in and through different situations and relationships. This relational approach can often be identified be by phrases such as ‘ well it depends on the circumstances for that person, it depends on the situation…’

Relationailty is an important part of such feminist thinking on care. Relationality emphasises and values that who one is characterised/constituted in and through one’s relationships with others. As Gilligan comments (online)

the ethics of care starts from the premise that as humans we are all inherently Relational , responsive beings and our human condition is one of connectedness and interdependence.

Bringing Relationality and Ethics Together: Gilligan’s In a Different Voice

Gilligan, an academic, mother and psychologist, worked at Harvard University as a research assistant for Kohlberg. Kohlberg (1958) had developed a widely used model of stages of moral development[1 in which the highest level of moral development is based on developing awareness and using reason and abstract ‘universal principles’ to make ethical decisions.

Gilligan, an academic, mother and psychologist, worked at Harvard University as a research assistant for Kohlberg. Kohlberg (1958) had developed a widely used model of stages of moral development[1 in which the highest level of moral development is based on developing awareness and using reason and abstract ‘universal principles’ to make ethical decisions.

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Source: https://schoolworkhelper.net/lawrence-kohlberg-the-six-stages-of-moral-development/

Gilligan was dissatisfied with Kohlberg’s model. For her, it did not fit with her experience as a mother living in an international community where she noted females tended to focus on responding to individual situations and fostering and maintaining interpersonal relationships.

Relational approaches to ethics and care-taking appear at the ‘conventional’or middle stages of Kohlberg’s model (see diagram above). Moreover, these approaches are described using disparaging terms(i.e. such as wanting to please the other and be seen by them as a a ‘good boy/girl). For Kohlberg, relational approaches are as a weakness compared with the higher level moral position of applying universal principles to situations. Women, who have a greater tendency to emphasise immanent ethics emerging in and through relating and responding to the other and their particular situation, are thus placed in a deficit position compared to similarly aged males (both adults and children) who do , as was observed by Kohlberg ,,have a stronger tendency to move through Kohlberg’s hierarchy to a position of using rationality and universal principles when faced with ethical decisions.

Gilligan (1982:484) highlights how:

The very traits that have traditionally defined the goodness of women, their care for and sensitivity to the needs of others, are those that mark them out as deficient in moral development.

Gillingham also identified that Kohlberg’s early research for the development of his model was carried out only with white males. She therefore carried out research of her own drawing on studies of children and university students and published her results and analysis in In a Different Voice (1982). She argues that that women are not deficient in moral reasoning. Rather, they use a style of reasoning that was not being valued by Kohlberg. Women’s have a stronger tendency towards an ‘ethics of care’: an approach in which ethical decisions respond to and build from on caring for others rather than from appealing to ‘seemingly’ universal reason and codes of behaviour (but which are instead codes based in particular ways of understanding the world and different power structures). Whilst this ‘ethic of care is not itself limited to females she argued it was more common among her female participants. She emphasis that such an ‘the ethic of care is as not designed to replace Kohlberg’s theory of morality, but rather to complement it’ (Ball 2010) and consistently argued that she would like to see psychology ‘free itself, both in theory and in methods, from the gender binary and the gender hierarchy’ (Gilligan cited in Ball 2010: online).

In a Different Voice was a landmark for the development of ‘difference feminism’ which ‘highlights the different qualities of both men and women but asserts that no value judgment can place upon them’ (Ball 2010). The approach was controversial. For example, some thinkers with accused the approach as essentialist i.e. women as having certain essential characteristics and tendencies.

In discussing these ideas Alison expressed surprise that relational approaches were still be disparaged in the 21st century, and women’s approaches seen as deficit to men’s. She asked is this really still the case? Sarah responded that, speaking from her own experience, she had until recently taught Kohlber’s stages of moral development as part of the teacher education curriculum. She also noted that she had done this without really questioning the high status afforded to the application of universal principles and the possible gender bias this can introduced.

What can these ideas contribute to our collaborative research which seeks new, more sustainable material relations for the 21st century?

Gilligan’s argument that women build ethical responses based on relationship and ‘care for and sensitivity to the needs of others’ opens new ways to value the other, both human and other- than-human. This can open up the possibility, through the material, the sensory, as well as the spoken word, to find new caring ways to be together in the world we share.

In future blogposts we will continue to look at different ideas developed in feminist ethics of care , including how these ideas can be extended into a new materialist framework where care extends not only to ourselves and other humans but also to the interdependent ecosystems currently facing unprecedented challenges.

Gilligan, an academic, mother and psychologist, worked at Harvard University as a research assistant for Kohlberg. Kohlberg (1958) had developed a widely used model of stages of moral development

Gilligan, an academic, mother and psychologist, worked at Harvard University as a research assistant for Kohlberg. Kohlberg (1958) had developed a widely used model of stages of moral development