Dr Osei Asibey Owusu is a medical doctor and a First Year PhD student in Clinical and Biomedical Sciences in the Faculty of Health and […]

Blogs

Improving Academic Presentation Skills: Reflections on HASS P2P RCA Event Series

Belinda (Dan Li) is a PhD student in the School of Education (SoE), within Faculty of Humanities Arts and Social Science (HASS). Her PhD is […]

Celebrating Dr Alan L. Hart: Revolutionary Advances in Tuberculosis Diagnosis through X-ray Imaging

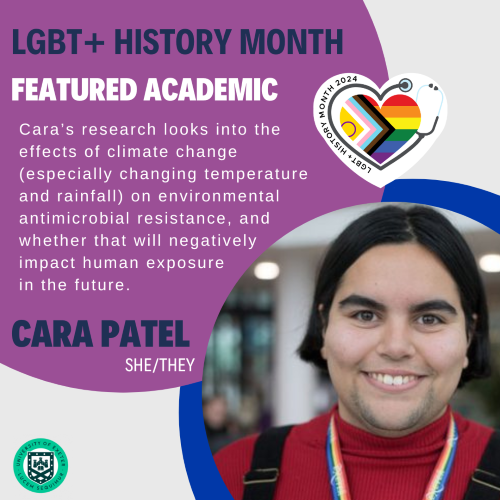

Cara Patel is a second year PHD student in the departments of Sports Science and Public Health (SSPH), Medical School, and European Centre for Environment […]

Unravelling The Future: AI Applications in Diagnostics

Dr Osei Asibey Owusu is a medical doctor and a First Year PhD student in Clinical and Biomedical Sciences in the Faculty of Health and […]

Starting my PhD journey as an ethnic minority student in a UK University

Dr Osei Asibey Owusu is a medical doctor from Ghana and postgraduate researcher in Department of Clinical and Biomedical Sciences within Faculty of Health and […]

Breaking the Silence: Normalising conversations about depression and anxiety in the PGR community

Tasha Hammond is studying for a PhD in Ecology and Conservation. She is based at Penryn Campus. My name is Tasha, I am a PhD […]

Doing a distance-based PhD before, during, and post-pandemic

Dr. Kris Hill, who completed her Anthrozoology degree this year, sat her living room in Berlin immediately after her viva. Learn more about Kris’s research […]

Ignore the headlines – international students are welcome here!

Anne Blanchflower is a final year PhD student in the Kurdish Studies Centre at the Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies (IAIS). She is researching […]

HASS P2P RCA Event Series – Public Speaking Skills in Academic Presentation

Hello! My name is Dan Li, or you can call me Belinda. I’m currently a 3rd year PhD in education and my research interests are […]

Planning, Preparing, and Presenting a Research Poster: Hints and tips for the Research Showcase 2023

Katy Humberstone, PhD candidate in Languages, Cultures and Visual Studies, and first place winner in the Humanities Arts and Social Sciences (HASS) category of the […]