Every day I read stories about men suffering through the horrors of the First World War. I should correct that: they’re not stories, they are real experiences, real lives and real facts. Necessarily, my research on the provision of film entertainment for British and Dominion soldiers during WWI means learning much about the lives of those who fought and died for their country: both the good times and the bad. As a researcher, it means confronting the harsh realities of war on a day-to-day basis, and despite being a century removed from the experiences found in the war diaries, newspapers and other documents I examine, the images and experiences I come across are no less harrowing, heartbreaking or poignant. Reading through the war diaries of a particular division or battalion, you begin to feel the ebbs and flows of the conflict, the highs and lows, the much needed periods of “rest” behind the lines and the dreadful anticipation of returning to the trenches. The casualty lists and statistics are staggering in themselves, but it is the personal narratives of loss and suffering that resonate the most. First-hand accounts of the conflict – descriptions of daily life on the front lines – places everything in front of you in a very real way. The immediacy, emotion and honesty that are found in the faded lines of a soldier’s diary, a diary you hold in your hands one-hundred years after it had made its way through the horrific conditions of trench warfare – even if its owner was not as fortunate – puts everything in perspective.

The fact that the same soldier visited a divisional cinema in the hope of forgetting, for a time at least, the horrors of the war is an equally moving sentiment. It’s very easy for us in the 21st Century to look back on the people who endured and suffered through the Great War, either at home or on the front, as being far removed from ourselves. Their lives must have been so different, we tell ourselves. Their interests and habits, how they passed the time and enjoyed themselves, seem so archaic. Many people today would find it difficult to place themselves in the shoes of such a person.

However, if I were to take one thing away from my research up to this point, it would be that the presence of the cinema on the front lines has compacted the distance in space and time between myself and those who fought in the war. Of course, the generation of men and women who experienced the war are exactly the same as us, with the same fears, hopes and desires. But for me, there is something very moving about the fact that whilst living through a conflict of such unprecedented scale and brutality, soldiers would turn to the cinema as a form of comfort and escape from the immediate dangers and disturbing sights of the battlefield.

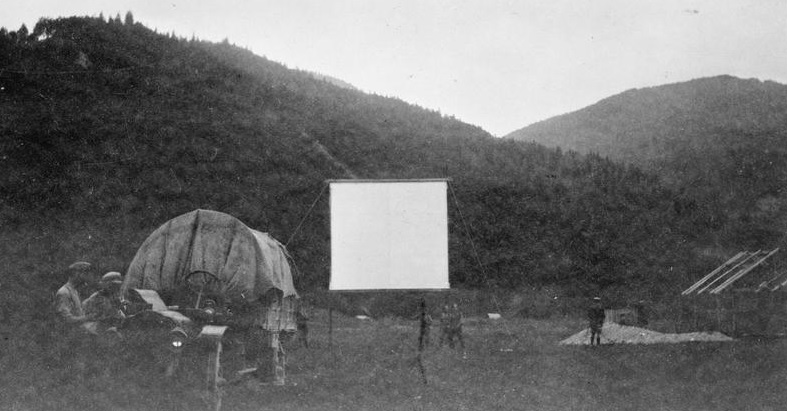

‘Fancy seeing a cinema show within the enemy’s shell fire!’ one soldier proclaimed in 1915. His disbelief may equal our own today, perhaps. The idea that the bulky, impractical technology needed to project film made its way on to the front line is a baffling notion in and of itself. Yet, dozens, even hundreds of makeshift cinemas did find a home on the battlefields of the First World War, established in dilapidated barns, shoddy huts or even in the open air. These cinemas, and the films they showed, most notably the films of Charlie Chaplin and other contemporary comedians, brightened the lives and raised the morale of those in the midst of the veritable hell on earth that the war had fostered. They turned to the cinema to ‘relieve the monotony and depression of trench warfare’. ‘It’s like being at home’ wrote another soldier, a sentiment shared by many. ‘Oh how we laughed – laughed as we had never laughed before’ proclaimed another about the antics of Chaplin. Like it is today, the cinema was a place where soldiers relaxed, met their friends and shared a laugh or two. On a day like today, it’s important to remember that these people were just the same as us, sharing the same interests and passions. Even with the distance of a century, soldiers would flock to front line cinemas just as we visit our local Vue or Picturehouse, for comfort, for friendship, to enjoy the film on screen and to escape, for a time at least, from the world outside.

______________________________________

After studying English Literature and Film Studies as an undergraduate at the University of Exeter (2010-13), followed by an MA in Film Studies at the University of Warwick (2013-14), Chris is now a PhD student at the University of Exeter. He is currently researching the history of cinema entertainment for troops at home and on the front lines during the First World War, a project which is supervised by Dr Joe Kember and Dr Debra Ramsay. His research interests include British silent cinema and the films of Charlie Chaplin. Read Chris’s research profile here.