Home » Articles posted by Katie Brown

Author Archives: Katie Brown

Postcards from the Year Abroad: Great Danes in a Northern German Manor House

Welcome to ‘Postcards from the Year Abroad’, a new series of blogs by students of Languages and Cultures at University at Exeter, giving us a glimpse into their year abroad experiences. First up is Nell Hargrove, who studies German together with Art History and Visual Culture.

I spent three months in northern Germany for my first placement on my year board in Autumn 2022. I lived in a Gutshaus with my two employers, Knut Splett-Henning and Christina von Ahlefeldt, their three children, two Great Danes, fifteen peacocks and Svamp, a kitten they found in the forest when mushroom picking (‘svamp’ is Danish for mushroom). Svamp the cat and the dogs, Triglaff und Svandevit were not the only Danish connections we had in the house. Christina is a Danish countess and her way of life and design inspirations are very much linked to her Scandinavian roots.

I spent three months in northern Germany for my first placement on my year board in Autumn 2022. I lived in a Gutshaus with my two employers, Knut Splett-Henning and Christina von Ahlefeldt, their three children, two Great Danes, fifteen peacocks and Svamp, a kitten they found in the forest when mushroom picking (‘svamp’ is Danish for mushroom). Svamp the cat and the dogs, Triglaff und Svandevit were not the only Danish connections we had in the house. Christina is a Danish countess and her way of life and design inspirations are very much linked to her Scandinavian roots.

Some say I was in the middle of nowhere (I quickly picked up the term ‘in der Pampe’) but even so, I managed to meet plenty of fascinating people. I keep a diary and in my first two weeks I met a new person each day. Ranging from artists to trendy Berlin weekend-breakers to locals, I treasure the conversations and insights they all offered me.

It was an extraordinary experience and everyday was different. Guthäuser (plural) are quite unique to the area of Northern Germany and Europe. They were commonly built between the 17th and 19th Centuries for the nobility and families of wealth. This is why they were regarded so negatively in the GDR years in East Germany because they were symbols of social hierarchy. This distaste for the Gutshäuser meant they became neglected and derelict during the 20th century. Knut and Christina are renowned in the region as the ‘Gutshaus-Retter’ because they are constantly taking on huge projects (at the time of my employment, they owned five Guthäuser!) to renovate and bring these falling apart mansions back to life. They even have a successful television show that has documented their work over the last nine years called ‘Mit Mut, Mörtel und ohne Millionen – Die Nordstory’ by NDR and I make an appearance in the most recent episode, knocking down a wall!

It was an extraordinary experience and everyday was different. Guthäuser (plural) are quite unique to the area of Northern Germany and Europe. They were commonly built between the 17th and 19th Centuries for the nobility and families of wealth. This is why they were regarded so negatively in the GDR years in East Germany because they were symbols of social hierarchy. This distaste for the Gutshäuser meant they became neglected and derelict during the 20th century. Knut and Christina are renowned in the region as the ‘Gutshaus-Retter’ because they are constantly taking on huge projects (at the time of my employment, they owned five Guthäuser!) to renovate and bring these falling apart mansions back to life. They even have a successful television show that has documented their work over the last nine years called ‘Mit Mut, Mörtel und ohne Millionen – Die Nordstory’ by NDR and I make an appearance in the most recent episode, knocking down a wall!

I learnt about real estate, ‘Denkmalschutz’ (monument/heritage conservation), hospitality and interior design. Knut had a very good eye for antiques and his wife Christina had formerly been a designer in Copenhagen and London. Gutshaus Rensow, the house we lived in, was built in 1690 and was bought by the couple in 2002. It attracts many guests via their website and Airbnb and has a capacity of 25 people. On three occasions, the whole house was booked for birthday parties and Knut cooked a very delicious roast dinner for everyone. Gutshaus Rensow has also featured in interior design and travel publications. Journalist, Rick Jordan from Condé Nast Traveller stayed for a long weekend and wrote an article about us for the January edition. Another feature of staying at Gutshaus Rensow in the winter was our only source of heating was a wood burner in each room. Guests and I alike would collect our wood in the morning and build a fire every day!

A highlight of mine was during the first week of October when galleries and art institutions across the whole of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (the Bundesland, like a county) took part in Kunst Heute, a week celebrating contemporary art by showing 133 exhibitions across the Bundesland. Not only did I visit as many as I could and take part in artist workshops, I helped an artist couple, Hubert and Miriam, set up their own art installation at Gutshaus Ramelow, the fifth Gutshaus owned by Knut and Christina.

I am glad I documented my time at Gutshaus Rensow so thoroughly because otherwise, I don’t think I would believe it happened – a truly unique experience and a time I won’t ever forget.

Nobel Prize in Literature awarded to “iconic” French writer Annie Ernaux

On 6th October 2022, Annie Ernaux was announced as the 119th winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, the 17th woman laureate in the history of the prize. Ernaux is a beloved and iconic writer in France and has been tipped to win the Nobel Prize in Literature for a few years now, yet despite her success in France and elsewhere in Europe she was relatively unknown outside academic contexts in the Anglophone world until the London-based independent press Fitzcarraldo Editions began to publish her work in translations by Alison L. Strayer and Tanya Leslie. By October 2020 Ernaux was Fitzcarraldo’s most published author, and at the time of writing the press has published eight of her works. This is also the third time that a “Fitzcarraldo author” has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature (the first two were Svetlana Alexievich and Olga Tokarczuk, and as Anna Cafolla notes in a recent Guardian article, the press also recently published 2004 laureate Elfriede Jelinek). For a young press founded in the spirit of risk, the impact of such a prestigious award cannot be underestimated.

All of the works by Ernaux that Fitzcarraldo have published in English translation are “white covers”, classified as non-fiction (the “blue covers” are Fitzcarraldo’s fictional works), a categorisation that indicates both the autobiographical nature and the historical significance of Ernaux’s work. Ernaux’s award was, the committee notes, for “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”, and indeed “collective” is a word frequently associated with Ernaux’s writing. From the “collective autobiography” The Years to the collective memory honoured through her personal experience in texts such as Happening and A Girl’s Story, Ernaux writes about her own life in a way that is inseparable from the time in which she has lived. The committee also mentioned Ernaux’s “clinical acuity”, a description of her writing that highlights her distinctive style: Ernaux writes deep and intense emotions with an observational composure that borders on detachment. In A Girl’s Story (translated by Tanya Leslie), Ernaux describes her own “minute attention to detail” regarding her relationships, and this attention to detail is as true of her writing style as it is of the content.

Almost all of Ernaux’s body of work is written as an attempt to order, make sense of, or immortalise her memories. The first of her books to be published by Fitzcarraldo in English translation was The Years in 2018, translated by Alison L. Strayer and awarded the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation in 2019. Widely regarded as her most important work, Ernaux’s opening line in The Years, “All the images will disappear”, both sets up and sums up her project: every memory of every life – from historical atrocity to TV adverts – will vanish at death, and so we must remember, bear witness, and claim a place in the world. Ernaux herself describes The Years as an “impersonal autobiography,” based on a collection of images and reflections, a narrative framed by photographs of the author at different points throughout her life. The girl and woman in the photographs is never explicitly named as Ernaux, but the series of photos provide the reference points through which her past – and that of her country – is narrated.

Perhaps the most harrowing of Ernaux’s works – and, to return to the Nobel committee’s summary, the most courageous – is Happening (translated by Tanya Leslie), in which Ernaux reconstructs her experience of a clandestine abortion in 1963, supplementing her memory of events with fragments of a journal she kept at the time. Ernaux makes frequent reference to both the act of writing and her sense of responsibility in sharing her story; specifically, she insists on the importance of articulating the reality of clandestine abortions, and the need to resist the complacency of remaining silent about past discriminations simply because they no longer happen. Ernaux demolishes such barriers of silencing and secrecy, putting into words her “extreme human experience” as both a chronicle of a brief period of her life in 1963 and a series of observations in parentheses which represent Ernaux’s reflections on living with the memory of the abortion that almost killed her, the process of writing about it, and how the narrative becomes a force of its own.

Common to both The Years and Happening, as well as to many other of Ernaux’s works, is a sense of responsibility: to record the experiences of her generation, and particularly the experience of women. This, for her, takes precedence over the potential reaction to her work, as she explains in a parenthetical statement in Happening:

“(I realize this account may exasperate or repel some readers; it may also be branded as distasteful. I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled. There is no such thing as a lesser truth. Moreover, if I failed to go through with this undertaking, I would be guilty of silencing the lives of women and condoning a world governed by the patriarchy.)”

Far from writing a repellent or distasteful text, Ernaux displays immense generosity and compassion in sharing her story. Through the public articulation of her intimate experience, she fulfils a sense of moral responsibility to challenge the patriarchal structures that order her experience of the world.

Throughout her œuvre Ernaux looks back on pivotal moments or relationships with a detached observation that belies deep emotion, and offers a portrait of a particular time, place and milieu that shaped her. In A Girl’s Story (translated by Alison L. Strayer) she exposes what it is to be a woman from a particular background at a particular time in history, in The Years she chronicles the personal impact of major historical events of the twentieth century, in I Remain in Darkness (translated by Tanya Leslie) she explores her mother’s decline from Alzheimer’s, and in A Man’s Place (translated by Tanya Leslie) she offers intimate portraits of her family. These observations – often focusing on women’s subjugation and/or lack of autonomy over their own bodies – are never separate from her personal experience, whether this be the experience of sexual desire in Simple Passion (translated by Tanya Leslie) or of her traumatic illegal abortion in Happening. Indeed, Ernaux is convinced that “of one thing I am certain: these things happened to me so that I might recount them. Maybe the true purpose of my life is for my body, my sensations and my thoughts to become writing” (Happening). By taking personal experience and offering it as literature, Ernaux both inscribes herself into history and uses her role as memoirist to give voice to a generation of anonymous women whose traumas have been systematically silenced.

Though Ernaux may be late to come to the attention of an Anglophone readership, her Nobel recognition was not an entirely unexpected or surprising choice. The prize notoriously favours European authors (indeed, Ernaux is the 16th French laureate) and in recent years has stated an intention to address its lack of women laureates (I might have ranted about this a few times). That Ernaux might be a good “fit” for the Nobel should not, however, detract from the importance of her work: a chronicler of her generation, a perspicacious observer of her own circumstances and the world that shaped her, and a writer with as much compassion as talent, Ernaux is an important author of our times whose work deftly blends the everyday and the momentous, the intimate and the universal.

Helen Vassallo

Associate Professor of French and Translation

Department of Languages, Cultures and Visual Studies

@translatewomen

Translating the Poetry of Birdsong

Poets across time and space have tuned into birdsong. Take the 9th-century Chinese Zen hermit poet, Han Shan (Cold Mountain):

| 寒山棲隱處

絕得雜人過 時逢林內鳥 相共唱山歌 瑞草聯谿谷 老松枕嵯峨 可觀無事客 憩歇在巖阿

|

Where Cold Mountain dwells in peace isn’t on a travelled trail when he meets forest birds each sings their mountain song sacred plants line the streams old pines cling to crags there he is without a care resting on a perilous ledge

Collected Songs of Cold Mountain, trans. by Red Pine (Copper Canyon Press, 2000), pp. 218-19

|

At the 2022 Translation Festival, Sally Flint in tandem with Hugh Roberts, Martin Sorrell and Yue Zhuang ran a session to ‘translate’ a favourite bird into a poem in a short burst of creative writing.

To celebrate National Poetry Day, here are the quick-fire poems produced at that session:

No sound, but a joyous song

A cold January morning in the garden alone.

Dad had died the day before.

A robin perched on a wheelbarrow.

Soundless – one eye watching.

The dark brown eye winked.

Like Dad’s pale blue eye,

It was a joyous song.

Bruce Currey

morning coffee

this birdsong is the first sign of spring

it sounds like an “ouh-ouh” to my ear

when I hear it I can feel the sun on my cheek

I can smell my dad’s morning coffee

I can even see the leaves resurfacing

and everything turning into shades of green

I didn’t know where it came from when I was six

but I knew it would be back next spring

Laurine Collardeau

black and white portrait

Fly. Perch. Now!

Down. Up. Check.

Velociraptor walk.

Inspect. Check. Look.

Eat. Pause. Check. Eat.

Eat. Pause. Check. Eat.

Cleverer than clockwork.

Cleverer than you.

Monochrome rainbow.

Hugh Roberts

And Martin Sorrell shared his beautiful translation of the ‘Chanson de l’oiseleur’ of the much-loved French poet, Jacques Prévert:

THE BIRD-CATCHER’S SONG

The bird that flies on silent wings

The bird that flies straight into things

The bird as red and warm as blood

The mocking bird the bird of love

The bird that’s eager to take flight

The bird that suddenly takes fright

The bird that has a panic fit

The bird that so much wants to live

The bird that so much wants to cheep

The bird that so much needs to weep

The bird as red and warm as blood

The bird that flies on silent wings

That bird’s your heart you poor wee thing

Your heart that’s fluttering its wings

Inside its cage of firm young ribs.

Translated by Martin Sorrell

Black History along Berlin’s Under- and Overground Network

In the 1920s, Black avant-garde dancer Josephine Baker enchanted not just the likes of Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway and Max Reinhardt but the wider public, including that of Berlin. A few years later, in August 1936, Jesse Owens thrilled the audience attending Berlin’s Olympic Games with his record-breaking performances. These are well-recorded biographical snapshots. Both celebrities paid only fleeting visits to the country: Baker’s home was in France; Jesse Owens returned with the rest of the team to the United States. Meanwhile, some of Germany’s lesser-known Black History can be traced through Berlin’s public transport system – telling stories of daily, no less extraordinary lives over several centuries.

I owe my first example to a Final Year student who referred to it during an oral exam in 2020. He expressed astonishment at his discovery of the quarter around ‘Afrikanische Straße’ while on his way to attend a sports training session. Berlin’s underground line number 6 connects Alt-Tegel in the northwest of the city with Alt-Mariendorf in the south – ‘Alt’ indicates former villages outside the city boundaries. During the Cold War, five out of overall 29 stops along this line were so-called ghost-stations in German Democratic Republic territory. Here, trains would slowly pass through the eerie darkness without stopping. This may be one reason why few of us took much notice of ‘Afrikanische Straße’: you hardly ever travelled this route without a reason. ‘Afrikanische Straße’ reflects that the street-names in the surrounding area are based on Germany’s colonial past: Swakopmund, Ghana, Togo, Windhuk, Kamerun and Sansibar mark the ambitions of the German Empire between 1871 and 1918. Initiatives to replace some of the names have taken a long time to materialize.

These references to Germany’s former colonies are also linked to merchant Carl Hagenbeck (1844-1913). He made his name trading wild animals and promoting zoos with more natural settings. Hagenbeck had ambitious plans for Berlin too. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, large zoos were not simply concerned with exotic animals. Instead, what appealed to visitors, including those of world fairs, were the so-called ‘living villages’ for ‘empirical study and education’. The German term ‘Völkerschau’ translates as ‘observing peoples’ – including their performances of dances and ‘typical’ rituals during opening hours. In Through the Lion Gate Gary Bruce has detailed some of the heart-breaking practices in Berlin where the most popular exhibits included people from

Lapland, Egypt and Cameroon.

Travel further southeast and, not far from the Brandenburg Gate, one encounters ‘Mohrenstraße’ on line 2. The badly war-damaged station on GDR territory was re-opened in 1950. After several name-changes in praise of German communists (Ernst Thälman, Otto Grotewohl) in 1991, following German Unification, the station’s name became Mohrenstraße. At that point, an urban myth about Mohrenstraße overshadowed everything else: rumour had it, that the spectacular marble inside the station stemmed from Hitler’s Chancellery – sending chills down one’s spine while passing through the station and marking a highlight for visitors touring Berlin. Alas, the marble was prepared after the war.

There is some speculation how the name of the nearby street Mohrenstraße came about – it may refer to slaves, former black residents or an African delegation, all can be linked to the 17th century. In fact, the archaic reference to ‘Moors’ dates back to the 16th century and was, usually, associated with Black Africans. To this day, one finds – in particular in Austria and Southern Germany – pharmacies and restaurants ‘Zum Mohren’; the practice to associate select chocolates and cakes with the term has stopped. Berlin’s Mohrenstraße caused repeated debates. In 2020, the murder of George Floyd renewed the interest in the name of the station. After the choice of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka had to be dismissed as a new name, the decision fell on Anton Wilhelm Amo who represents yet another layer of Germany’s Black History.

There is some speculation how the name of the nearby street Mohrenstraße came about – it may refer to slaves, former black residents or an African delegation, all can be linked to the 17th century. In fact, the archaic reference to ‘Moors’ dates back to the 16th century and was, usually, associated with Black Africans. To this day, one finds – in particular in Austria and Southern Germany – pharmacies and restaurants ‘Zum Mohren’; the practice to associate select chocolates and cakes with the term has stopped. Berlin’s Mohrenstraße caused repeated debates. In 2020, the murder of George Floyd renewed the interest in the name of the station. After the choice of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka had to be dismissed as a new name, the decision fell on Anton Wilhelm Amo who represents yet another layer of Germany’s Black History.

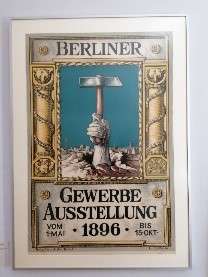

Travelling on (by now over-ground) towards Berlin’s south eastern suburbs, the local museum in Treptow (https://www.museumsportal-berlin.de/en/museums/museum-treptow/) provides an exemplary approach to Germany’s colonial past. Together with other museums and the Initiative Black People in Germany and Berlin Postkolonial, in 2017 Treptow housed a small and powerful exhibition based on the Berlin Trade Exhibition (Gewerbeausstellung) of 1896. In 2021, ‘zurückgeschaut / looking back’ (in cooperation with Dekoloniale Memory Culture in the City) expands the original approach.

The Trade Exhibition of 1896 attempted to emphasize German commercial and scientific achievements and to affirm the role of the relatively new German capital of Berlin. To visualize the message, Germany’s presumed modernity was set against the exotic ‘natives’ villages’ organized for the occasion. This part of the Gewerbeausstellung ‘aimed to create the greatest possible difference between the population of the “cosmopolitan city” with its alleged “refined customs” and “proud splendour” and the colonised people who would supposedly bring an element of “natural wilderness” and “rawest culture” to the banks of the Spree river.’ One of the exhibition rooms displays the photographs of those who had been lured to Berlin – their work contracts had not clarified that they would be exhibited. While most returned home once the Gewerbeausstellung had closed, twenty stayed, married and had children.

The Trade Exhibition of 1896 attempted to emphasize German commercial and scientific achievements and to affirm the role of the relatively new German capital of Berlin. To visualize the message, Germany’s presumed modernity was set against the exotic ‘natives’ villages’ organized for the occasion. This part of the Gewerbeausstellung ‘aimed to create the greatest possible difference between the population of the “cosmopolitan city” with its alleged “refined customs” and “proud splendour” and the colonised people who would supposedly bring an element of “natural wilderness” and “rawest culture” to the banks of the Spree river.’ One of the exhibition rooms displays the photographs of those who had been lured to Berlin – their work contracts had not clarified that they would be exhibited. While most returned home once the Gewerbeausstellung had closed, twenty stayed, married and had children.

By the 1920s, Berlin had become a cosmopolitan metropolis. In 1927, the German communist Willi Münzenberg took actively part in the ‘First Congress against Colonial Repression and Imperialism’, followed in 1930 by the ‘International Conference of Negro Workers’ in Hamburg. In Berlin, a new underground station in the south west of the city was named Onkel Toms Hütte / Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1929 in reference to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel of 1852. The station provided the modernist housing estate of the same name with access to the city-centre.

However, by the 1930s Germany’s history caught up with some of the children of those who had remained in the country. Martha Ndumbe, daughter of Duala Jacob Njo Ndumbe, died in Ravensbrück concentration camp on 5 February 1944. Josefa van der Want, a Black German dancer and daughter of Josef Bohinge Boholle, died in 1955 ‘from the late effects of the imprisonment in a concentration camp’. Meanwhile, Josephine Baker, the celebrated star of 1920s Berlin, joined the French Resistance against the German occupiers during the Second World War and earned the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance.

After the Second World War, with the occupation and division of Germany a new, at times no less challenging chapter for Black History in the country started. Today, about 1 Million Afro-Germans or Black Germans are resident in Germany, predominantly in large cities, including Berlin.

Students Re-Imagine Baudelaire: Through the Window and Into the Clouds

In September 2021, we welcomed returning final-year students back to their studies with a series of refresher classes after all the disruptions of 2020-21.

For one set of these classes, we set grammar books to one side and extended the great French poet Charles Baudelaire’s ‘Invitation to a Voyage’ to students. He claims that each one of us has an internal supply of natural opium to inspire and enthral us. In other words, the poet invites us to engage the limitless potential of our imaginations. Taking a leaf out of Baudelaire’s book, this particular class was to be an exercise in creative translation with an emphasis on the imagination.

Students looked briefly at one out of a pair of Baudelaire’s prose poems, namely ‘L’Étranger’ (‘The Stranger’ see English translation here) and ‘Les Fenêtres’ (‘Windows’, available in French and English translation here). They then had 15-20 minutes to produce their own version of it, by imagining their own encounter with a stranger in the clouds or by looking through a window in their mind onto a place of particular resonance for them.

The results are remarkable, a testimony to the innate creativity of our students who have already had to draw on their imaginations to think and be in another language. We also celebrate Baudelaire, who would have turned 200 in 2021, by extending his invitation to a voyage of the imagination.

Here’s the first set of poems based on ‘L’Étranger’:

In the clouds

- Are you alone here in the clouds?

- It is dark, it is raining.

- You are mysterious.

- I am not mysterious, I am afraid.

- You are afraid?

- Of light? Of darkness? Of joy? Of sadness?

- Of the world.

- But look down! The world is bright, the world is happy, the world is for everyone.

- So, why am I up here in the clouds?

Hannah Croutear

- So what’s your gimmick, then, Mr. Woke? Tell me about your family.

- I don’t have any worth speaking of, no parents or siblings.

- No friends then either?

- People come and go, for better or worse.

- And where do you come from?

- Many places, but what of them?

- And beauty?

- I see it everywhere, almost spiritually.

- Do you want riches? And fortune?

- Doesn’t seem to build a good lifestyle.

- So what do you even care for, since you have nothing left?

- Don’t you feel the breeze today? It’s so good to be here, wherever that is.

Afterthought:

Les richesses, et la fortune. Le sort. C’est quoi, sans les efforts pour les atteindre? C’est quoi, la vie, quand elle est remplie par les bêtises? C’est quoi, une maison, quand elle manque la porte? Et c’est quoi, une porte, quand elle attend toujours quelqu’un? Mur. Je vis, mais seulement quand les murs me permettent.

Mark Evans

En regardant les nuages rosâtres trébucher les uns sur les autres,

Je me demande serai-je jamais content ?

Le bonheur interne qui me manque devrait exister quelque part.

J’en suis sûr. J’en suis tellement sûr que ce néant me fait mal.

Les nuages quittent le ciel, révélant un azur aveuglant,

Avec son soleil fulgurant qui me brule les yeux

Et ses rayons qui embrassent ma peau,

Tout en déchirant mon corps en morceaux de l’intérieur.

Cependant, cette douleur me faire sentir à l’aise,

Elle me rappelle que je suis encore vivant

Soit à contrecœur, soit à dessein.

Jacob Farrington

-My body leaves me, floating in pure darkness. The silhouette asks, what is it like?

-It’s having no sensations, no responsibilities, no existence except from serenity.

-What was life like before? Says the silhouette

-Full of living, of existing, that world is still there but nowhere to be found.

-Is there fear?

-Not here

-Do you want to leave?

-Here I am a cloud, floating with no feeling, coming and going, sometimes existing, sometimes not.

Erica Harris

- Why is there only light?

- Because there is no darkness

- Where is the blue?

- There are only in orange and reds.

- What about words?

- There is nothing to say but to melt like the sun.

- And when does the sun rise?

- It only sets, moving towards the pink dusk.

Rhian Hutchings

Il se balade

Ses pas tombent avec soin

Sur le sol qu’il méprise

Plutôt, il préfère le ciel

Les nuages

Les autres, ils regardent leurs pas

Ses pensées sont à Terre

Mais il ne les connait pas

Il ne connait personne

Sauf ses amis nébuleux

Éphémères

Une fois rencontrés, ils disparaissent à jamais

Toujours différents, mais familiers tout de même

Cette amitié, c’est tout ce qu’il lui faut

Car le ciel le reflète

Toujours seul et jamais seul

Le ciel ne le quittera jamais.

Emily Maynard

He wanders

His feet tread carefully

Along the ground he ignores

Rather, he prefers the sky

The clouds

The others all stare at their feet

Their thoughts are of Earth

But he does not understand them

He does not understand anyone

Apart from his friends in the sky

Fleeting

Soon after meeting, they disappear forever

Always different, but familiar all the same

This friendship is all that he needs

Because the sky reflects him

Always alone and never alone

The sky will never leave him.

translated by Emily Maynard

Les Nuages

I’m watching the clouds,

They pass like time and life, across an ambiguous sky,

Will they darken and bring rain and life with them,

Or will they burn away and reveal the splendid sun above,

Revitalising, yet cruel.

The clouds intertwine, transforming into faces I once knew

And mesmerising patterns, drawing me further into my reverie…

A swallow soars upwards, undulating in the sky, headed towards the infinite universe above…

I wonder where she is she destined,

Is she returning home, to comfort and familiarity,

Or onwards, to new lands and uncertain skies,

To new ventures and risks,

Through turbulent tempests or over calm seas,

Skimming over waters of far-away lakes and oceans?

I will never know.

I wish her well with a nod of my head

And ponder what I’ll have for dinner…

Hannah Hall

And to conclude a pair of poems inspired by ‘Les Fenêtres’ (‘Windows’).

The sun bounces off the waves gently, casting a dim shadow in front of me as I look out over the sea. The small beacon of the lighthouse has lit up, a relic of safety from years gone by. We watch as the haze on the horizon creates murky skyscrapers, which rise from the sea as a lost city. Then, they pass, and we are left watching the container ships which have taken their place. Hundreds of goods transported from A to B. A floating island made of metal and oblivious to the numerous voyeurs on the shoreline.

A woman walks past on the beach with her dog, stopping only to pick up stones to throw for him. I wonder how far she has travelled to get here.

The window has a calming glow to it, a lulling sense of safety which beckons as if the warmth of the lowing sun is beating through it.

Isabelle Ferguson

The Window

I rise from my stupor, in the stuffy, shadowy room I call home in Exeter. I move lightly, guided by some deep yearning within me and open my window.

What awaits me is the most bright, bustling, and brilliant sight. My gaze settles on a waiter. His uniform pristine, his face set in a perfect, polite smile. He carries two overflowing flutes of deep golden liquid.

When he lays them on the ornate table bathed in perfect evening sunshine, my attention shifts to the women who grasp these glasses with fervour. Their skin is rosy, pricked by the strength of the sun’s rays.

The bustle softens, the music fades and what is left is the sound of their laughter. What beauty in that joyful noise? What envy to be as carefree as their shrieks of laughter sound?

I leave my room and join them, through my open window. The metal chair feels cool against my legs in this humid plaza in Northern Italy. Cold, bubbling, golden liquid glides into my mouth, leaving a trail of sticky warmth within me. I am boxed in by bold, boisterous buildings. Our table is pressed into a corner and yet I am the freest I’ve ever felt.

Sacha Warne

A Multilingual Celebration of Poetry

For the Festival of Discovery at the University of Exeter, staff and students from Modern Languages and Cultures gathered to share, translate and enjoy poetry in multiple languages.

A session on Colourful Language was a chance to reimagine a poem about language and colour in whatever language or idiom students chose. You can read the original poem, ‘Voyelles’ by the visionary French poet Arthur Rimbaud (written in 1871, when he was 16 years old), and a translation into English on Wikipedia.

A session on Colourful Language was a chance to reimagine a poem about language and colour in whatever language or idiom students chose. You can read the original poem, ‘Voyelles’ by the visionary French poet Arthur Rimbaud (written in 1871, when he was 16 years old), and a translation into English on Wikipedia.

Two students on the MA in Translation, Juliana Galán and Maria Florencia Fernández, have shared their versions with us. They translated the colours and images of the original into ones that speak of the landscapes of their Latin American homelands, demonstrating the diversity of Spanish across the continent.

Maria Florencia Fernández says: ‘I focused on the sounds and alliteration to convey what the vowels/colours mean to me, and I gave it a bit of Argentinian flavour with the pampas.’

A negro, E blanco, I rojo, U verde, O azul

Un día contaré qué hace cada vocal

A, enjambre negro de bichos que zumban

Amontonados alrededor de la podredumbre

Golfos en las sombras; E, candor vacío – nieblas y tiendas,

Flechas heladas del glaciar, reyes blancos, flores temblorosas;

I, púrpura, sangrienta, risas desde labios encendidos

De furia o penitencia ebria;

U, giros, vibraciones divinas de mares verdosos,

La paz de las pampas donde las aves revolotean, entrecejos que se suavizan

Cuando el alquimista cree haber logrado su premio

O, trompeta estridente suprema, silencio atravesado

Por mundos y ángeles que sobrevuelan – O,

lánguida letra perdida, omega, rayo alilado… Sus ojos…

Juliana Galán wrote ‘My translation does not take a literal approach. It does keep some of the same words and remains close to the text, but I mainly took the images and feelings that the author’s description evoked in me, social situations, politics, landscapes, nature, and my own memories. My translation is localized in Colombia and is driven by feelings and my heart.’

Vocales

A negro, E gris, I rojo, U azul, O dorado

Un día habré de hablarle a las vocales de su magia.

A, la muerte en traje de batalla, negra mortaja bañada en lágrimas saladas,

Las manos suplicantes de madres desesperadas

Playa al amanecer; E, candor gis – neblina y chinchorros,

Malocas y ciudades sagradas en las sierras altivas, hermanos sabios y gentiles, cardúmenes de peces sierra,

Alas que reposan en la ciénaga.

I, rojo, latidos y palpitaciones, mejillas delatoras, rostros del altiplano, labios expectantes,

El fin del día, el amor, la ira y la vida.

U, olas; vibraciones divinas de océanos infinitos

Media noche, profundidad insondable, vidas ocultas, bitácora de la humanidad

Cyan de cielos de verano, días de sol, burbujas etéreas.

O, celestial trompeta estridente, silencios atravesados de cuerpos fugaces

Aleteos de ángeles laboriosos,

O, la última letra olvidada, Omega; Helios, su rayo dorado

La divinidad, la luz, su alma.

You can listen to Juliana read her poem here.

A few days later we reconvened to share poems and songs in languages from Arabic to Welsh, including the indigenous languages of Mapuche and Quechua (click here to listen on Spotify).

While most of us shared works by other people, Laurine Collardeau shared a poem of her own in French. Laurine is a student of French literature at the Sorbonne who joined us from Paris as an Erasmus student.

Laurine says: ‘When I wrote ‘Empreientes’, I just had finished reading Proust’s A l’Ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (1919), the second book of Proust’s novel A la Recherche du Temps perdu, which is about adolescent ego development, the first stages of love, memory, the experience of art… all at once. As I was reflecting on how memory works, I found it fascinating that people always leave something in us. This means that they don’t really leave a feeling but rather the remembrance of the time when the relationship took place. This is what the term ‘Empreintes’ (i.e. ‘footprints’) refers to. I like the idea that people leave footprints behind and that you are still able to follow them, yet footprints are sometimes misleading. Therefore, we tend to remember the best of someone and rarely the reasons why the relationship ended. This poem is a bit messy, which makes sense considering I’m stepping into adulthood and am right in the middle of figuring things out – if they can ever be figured. I write with what we call in France écriture inclusive which means I have not specified genders. This explains the use of a dot followed by an ‘e’ at the end of adjectives.’

Empreintes

Soudain comme un début in media res

J’ai vu ton visage au son du clocher

De la ville dont nous voulions nous échapper

Comment vas-tu ?

Qu’est devenu l’homme qui vendait des fruits au coin de ta rue ?

Le marchant de CD a déménagé

Son enseigne est un nouveau prêt-à-porter

Il faut construire pour enterrer le passé

Comment vas-tu ?

As-tu relu les notes que j’avais laissé dans tes revues ?

Si on avait su…

Je porte toujours les chaînes d’un bracelet aux paroles non tenues

Si mon adolescence n’est plus sur mon visage elle est sur le tien

Sur une silhouette qui me surprend à chaque fois que je la vois au loin

Sur un arrêt de bus qui me demande si je dois poursuivre mon chemin

Rien n’est fini

Si tout devient ruines

Tu es parti

Tes empreintes restent humides

Le futur faisait peur mais je t’y voyais

Sur des cartes aux distances déjà toutes tracées

Plains les trains fantômes de m’avoir éloigné.e

Que disais-tu ?

Te découvrir c’est comme être frappé pas un doux déjà-vu

Des tours de magie cèlent les amitiés

Je m’attendais à te voir t’évaporer

À entendre le silence quand j’ai décroché

Que dirais-tu?

En voyant que je lis encore les livres que je ne t’ai pas rendu

Si j’avais su…

Qu’aimer trop jeune c’est être incapable de vivre avec une vielle rancune

Si mon adolescence n’est plus dans mon langage elle est dans ta voix

Dans un nom qui hante l’aube de lettres qui n’ont pas survécu l’envoi

Dans des promesses qui reposaient sur l’interdiction des aux revoir

Et je suis sûr.e

Que tu les as tenues

Car les gentils voisins racontent que tu ne savais pas t’exprimer

Que l’on te reconnaissait mieux de dos à force d’avoir essayé

De fuir mais moi j’ai suivi des yeux les empreintes pour te retrouver

Je ne sais plus

Quand le soleil s’est levé

Mais d’autres sont venus

Et tes empreintes ont séché

Footprints, translated by Professor Hugh Roberts

Suddenly like a start in the middle

I saw your face at the sound of the bell tower

Of the town from which we wanted to escape

How are you?

What’s become of the man who sold fruit at the corner fruit of your street?

The CD shop has moved

Shop sign is for a new clothing store

You have to build to bury the past

How are you?

Have you reread the notes that I left in your magazines?

If we had known…

I still wear the links of a bracelet of unkept promises

If my teenage years aren’t seen on my face any longer they’re on yours

On the shape of your body that surprises me each time I see it from afar

When the bus stops and made me wonder if I must carry on my journey

Nothing is over

If all becomes ruins

You left

Your footsteps are still warm

The future was scary but I saw you in it

On maps on which distances were already marked out

Pity the ghost trains which took me away

What were you saying?

Finding you again is like getting hit not a sweet déjà-vu

Magic tricks hide friendships

I was waiting to see you vanish

To hear the silence when I hung up

What were you saying?

As I see I’m still reading the books I didn’t return to you

If I had known …

That loving too young is to be unable to go on living with an old grudge

If my teenage years are no longer in my langauge they’re in your voice

In a name which haunts the the dawn of letter that didn’t survive being sent

In promises which depended on forbidding farewells

And I’m sure

That you’ve kept them

For the nice neighbours say you didn’t know how to express yourself

That they recognized you better from behind by dint of your always trying

To flee but me, my eyes followed your footsteps to find you again

I no longer know

When the sun came up

But others have comes

And your footsteps have dried

If you have been inspired to write your own poem based on something you’ve read, please share it with us. Or just share your favourite poems and songs in any language in the comments.

Recent Comments