Posted by lr299

18 February 2017I’m very much looking forward to joining the community at Exeter this coming autumn, and I would like to take the opportunity to introduce myself and my work.

Currently I’m finishing up a project: a study of saints from abroad in early medieval Rome. The city of Rome guided me to this project. Wandering through Rome—one of my favorite pastimes—led me to puzzle about the city’s many saintly presences. On the Tiber Bend, for example, we find, in close vicinity, churches for the marvelous wonder-worker St. George, the soldier-saint Theodore and, conveniently close to the Tiber, for St. Nicholas, a bishop with a reputation for assisting travelers in distress.[i] All three of these saints are ‘saints from abroad’, that is, saints who, according to their hagiographical legends, lived and died in locations outside of Rome. What are these saints doing in Rome?

The rise of ‘Christian’ Rome tends to conjure up images of Peter and Paul and the catacombs with their many martyrs. In the words of Ferdinand Gregorovius’ magisterial (1869-1872) History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, a new Rome ‘rose again from out of the catacombs, her subterranean arsenal’, her Empire ‘transformed into an ecclesiastical system, with the pope as its center.’[ii] But when we look within the city walls we find that the new spiritual topography was shaped, as much, if not more, by saints from abroad.

The period I’ve considered is from roughly the 6th to 9th centuries. This isn’t because saints from abroad weren’t present in the city beforehand. Already the earliest list of saints venerated in Rome, the mid-5th-century Depositio Martyrum, includes North African saints: St. Cyprian and Sts. Perpetua and Felicita.[iii] Nor, of course, does the introduction of saints from abroad come to a halt in the 9th century. However, the reason to focus on the period from shortly before the ‘reconquest’ of Italy by Justinian’s armies in the mid-6th centuries through the 8th century is that this was a period in which Rome was still very much part of the ‘Byzantine’ world of the Eastern Mediterranean. Correspondingly, saints who belonged to the ‘cultural koine’ of the late antique/early medieval Mediterranean world readily settled in Rome.

The story I’ve tried to piece together is how and why these saints were settled in Rome and what impact they had on the city. It is a story of Byzantine administrators and Roman ecclesiastics, but also of communities of immigrants and Romans, their names long forgotten, who patronized saints from abroad for the protection and support these saints offered. Fragmentary as the evidence is, it helps wrench us away from an image of a monolithic papal Rome that grew out of its own ‘native’ sanctity.

The presence of these saints in Rome reflect their patrons’ Mediterranean horizons. Once in Rome their legends maintained the memory of the far-flung locations from which they were purported to originate, adding particular inflexion to the city. Moreover, these saints, just like their Roman counterparts, were in dialogue with the monumental Roman past into which they entered, imbuing it with new Christian meaning.

Take St. Hadrian. According to his passio, St. Hadrian was an administrator who converted to Christianity and was martyred in Nicomedia. His relics were said to have been brought to Constantinople soon after his death. What better location in Rome for a Constantinopolitan administrator-saint than the Senate House!

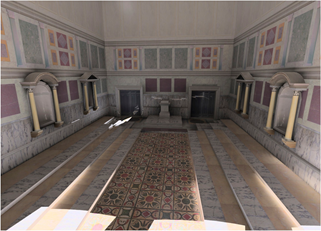

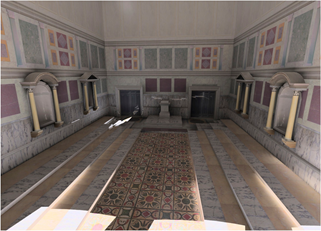

Reconstruction of the Interior of the Senate house: UCLA Digital Forum. Photo Credit: Curia interior, UCLA Experiential Technologies Center, © Regents, University of California

When Pope Honorius (r. 625-638) dedicated the senate house to St. Hadrian the architectural changes were minimal. The marble revetment and benches where the senators had once sat remained in place. This was then a site that continued to hearken to its imperial legacy and yet, whose saint proposed a radically new vision of empire. A new Rome was taking shape, still grounded in its imperial, Mediterranean, past.

Dr Maya Maskarinec, Lecturer in Medieval Mediterranean History

[i] The earliest surviving written attestations of a church dedicated to Nicholas at the Tiber bend date from the time of Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099). However, circumstantial evidence (in particular a column inscription from within the church) suggests a significantly earlier date.

[ii] Ferdinand Gregorovius, Geschichte der Stadt Rom im Mittelalter: vom V. bis zum XVI. Jahrhundert (1859–1872), edited by W. Kampf, 4 vols. (Munich: C.H. Beck, 1978; first edition 1953-57); trans. A. Hamilton, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, 8 vols. (London: Bell, 1894–1902), here 1.1, pp. 10; 17-18.

[iii] Depositio Martyrum, ed. R. Valentini and G. Zucchetti, in Codice topografico della città di Roma II, Fonti per la storia d’Italia 88 (Roma: Tipografia del Senato, 1942): 17-28.