Research institutions come in all shapes and sizes. As medievalists, we’re used to the rhythm of a good ‘archives trip’: the early start, the queuing to get the readers’ card...

Continue reading...

Research institutions come in all shapes and sizes. As medievalists, we’re used to the rhythm of a good ‘archives trip’: the early start, the queuing to get the readers’ card...

Continue reading...

As the days start to lengthen and the lecture halls begin to fill up, the gears of the Centre for Medieval Studies are spinning up once again for 2024. We...

Continue reading...

The Centre for Medieval Studies here at Exeter plays host to a number of reading groups. One of these, the Medieval French Reading Group, recently celebrated the end of term...

Continue reading...

A heartfelt thank-you to Yolanda Plumley from her friends and colleagues in the Centre for Medieval Studies.

Continue reading...

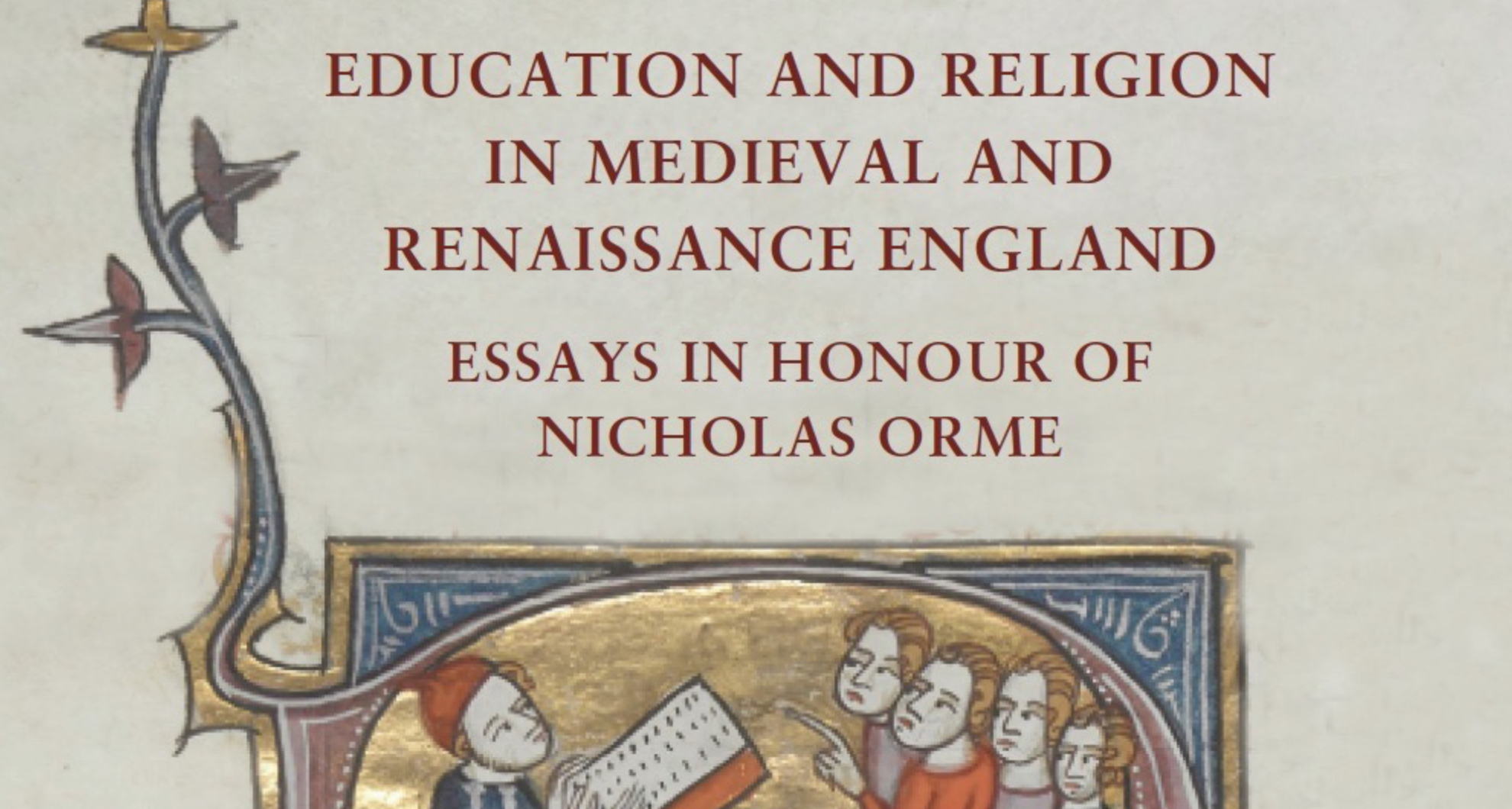

A new book, Education and Religion in Medieval & Renaissance England, honours our colleague, Emeritus Professor Nicholas Orme, for his outstanding contribution to the study of cultural and religious life...

Continue reading...Dr John Slevin, former Exeter PhD student and editor of the newly published History of Alfred of Beverley, completed his doctorate as a mature student and distance-learner. Beginning and completing...

Continue reading...We are very happy to announce the publication of an edition and translation of The History of Alfred of Beverley by one of our former PhD students, Dr John Slevin,...

Continue reading...In medieval England Queen Consorts were not the only women whose status and style of life were changed forever at the coronation of a king. Crowning conferred on the monarch...

Continue reading...The relationship between a mother and a teenage daughter is often represented as inherently volatile. It has a long history as a trope in drama and fiction and in spite...

Continue reading...Emily Selove, Senior Lecturer of Medieval Arabic Literature in the University of Exeter’s Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, has published a book of cartoons about the medieval city of...

Continue reading...The Douce manuscripts and printed books, held in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, are one of the most remarkable medieval collections to have been put together by a single bibliophile. In the...

Continue reading...Just when Lockdown 1 began I’d started to think about the acknowledgements I would include at the front of my new book, The Dissolution of the Monasteries. A New History....

Continue reading...This is the second part of the students’ interview with Alice Taylor, an expert on medieval Scotland. This part of the discussion covers the concept of “culture wars”, the impact...

Continue reading...Last month, students on the Special Subject module ‘The Celtic Frontier: Post-Conquest England and her Celtic Neighbours’ were given the opportunity to interview Dr Alice Taylor, an expert on medieval...

Continue reading...Have you ever come across mysterious references to medieval heretics and their violent repression and wished to know more? Have you ever wondered about those signs welcoming you to the...

Continue reading...As the present benefits of study abroad (and the Erasmus programme in particular) are in the spotlight, it is worth considering a past example: a beautiful manuscript book copied and...

Continue reading...Being Human is an annual festival in celebration of the humanities, organised by the School of Advanced Studies at the University of London. Exeter’s medieval studies community has a history...

Continue reading...Today, Tynemouth Priory looks a likely place for a haunting. The ruin stands tall and gaunt at the high point of the windswept Northumberland coastline. Advancing towards its hollow east...

Continue reading...

David Bates, who received his PhD from the University of Exeter in 1970, has been awarded the prestigious Prix Syndicat national des Antiquaires du Livre d’Art 2020 for the book La...

Continue reading...Five months on from our previous post, work has been proceeding apace at the ‘Learning French in Medieval England’ project — or, as literally no-one is calling it, ‘Tretiz Towers’. Our primary...

Continue reading...On 1 October 1536 a crowd of worshippers which had just spilled out from the parish church of St James at Louth (Lincs.) was stirred into shouts of angry protest...

Continue reading...

It’s the start of a new academic year at Exeter and many things are different. We can’t teach, research, or meet together as a community in quite the same way...

Continue reading...Writing in 1879, the great Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins bemoaned the recent felling of the poplars at Binsey near Oxford: ‘All felled, felled, are all felled’. To him, those...

Continue reading...Five hundred years ago this week the monarchies of England and France met in the meadowland of the Pas-de-Calais. Today these flatlands are largely nondescript for the traffic that flashes...

Continue reading...

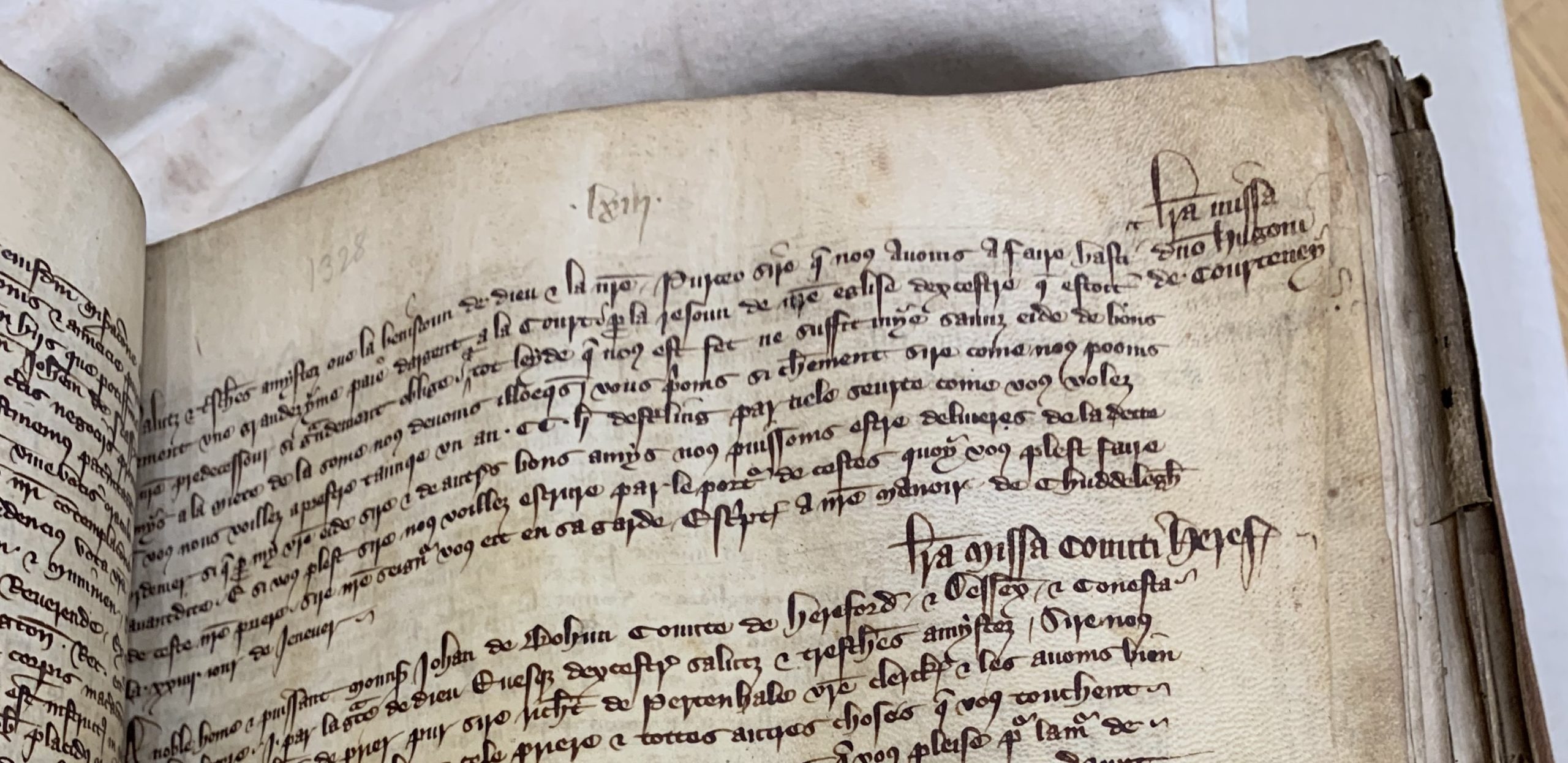

Almost ten years ago, during my doctoral research, I was rifling through boxes at the Archives nationales in Paris for the first time. Guided by preliminary references I had found...

Continue reading...Just over two months ago, we announced the start of a new project based at the Centre for Medieval Studies here in Exeter: Learning French in Medieval England. Our aim...

Continue reading...Since I’ve been on maternity leave I’ve not surprisingly been pondering all things to do with pregnancy and baby care. I’ve also been thinking about medieval pregnancy advice, since it’s...

Continue reading...

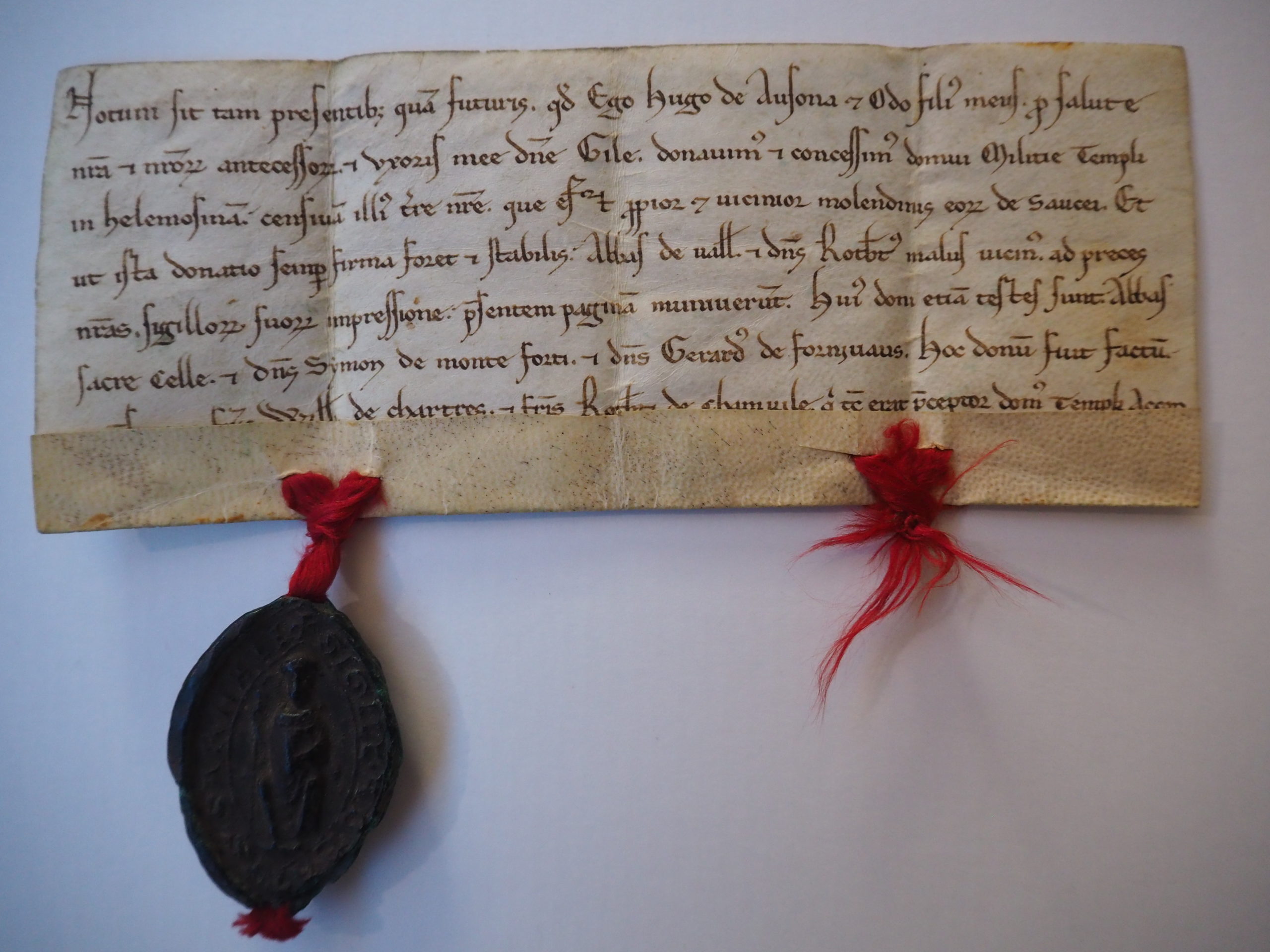

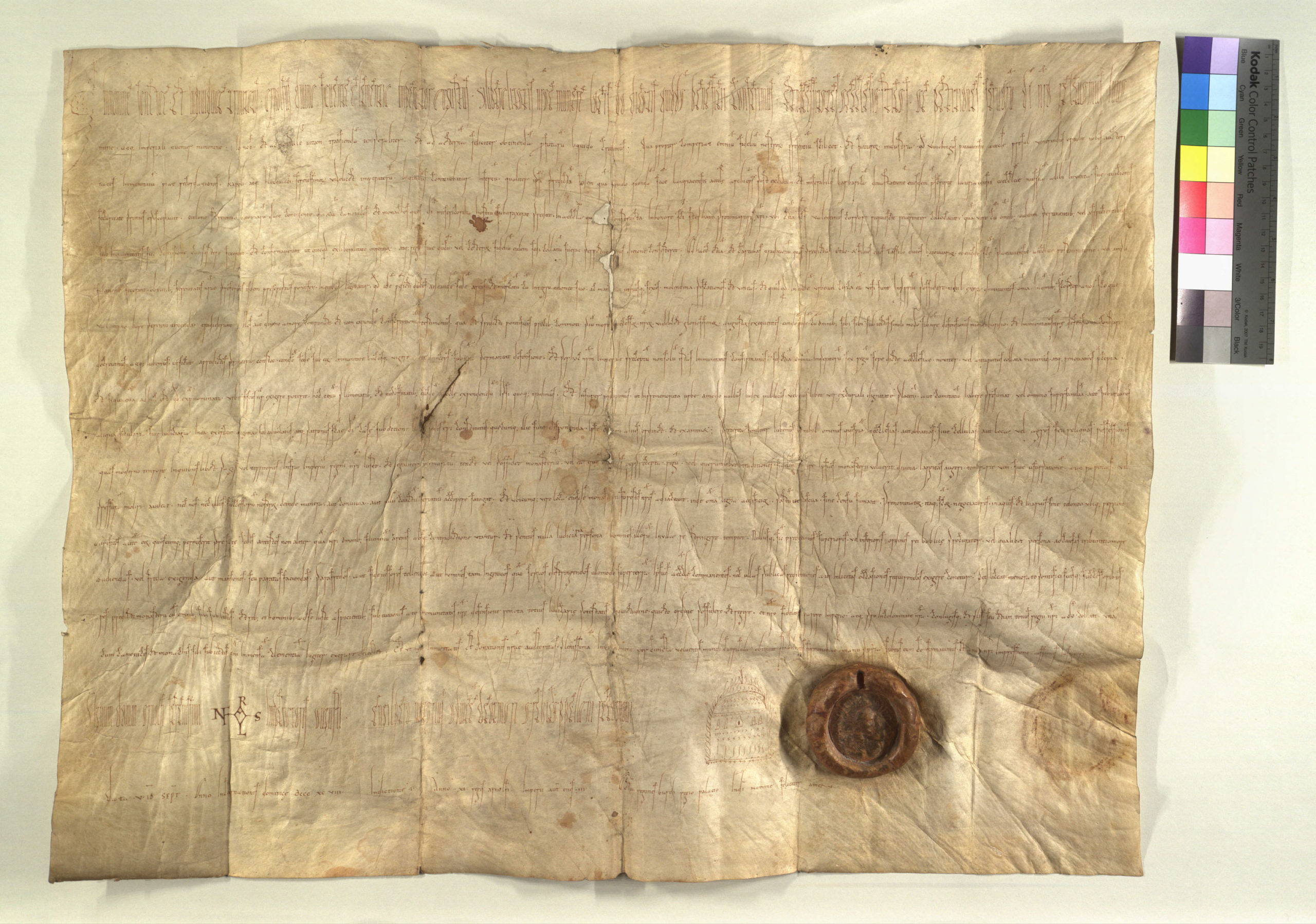

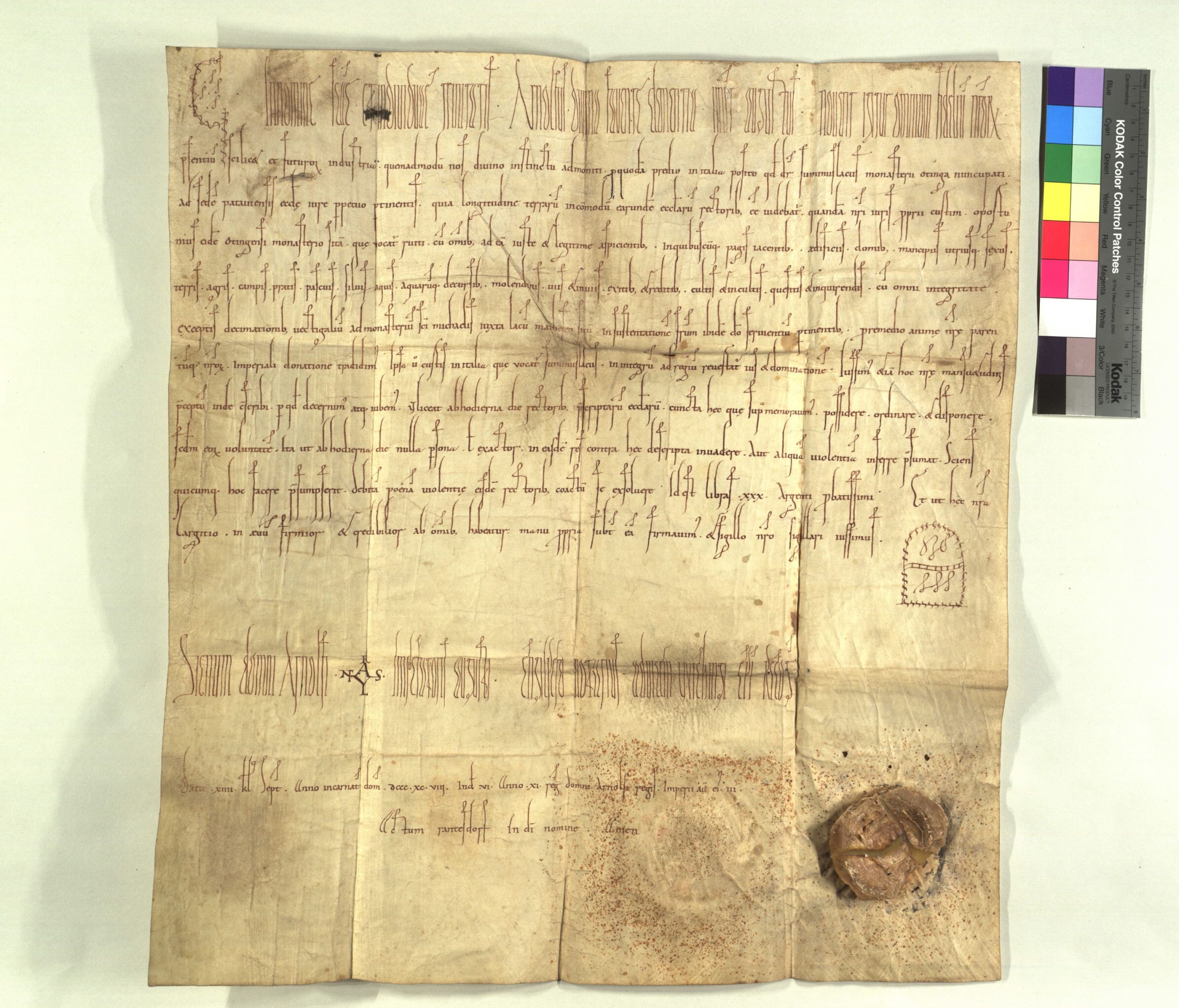

One of the most striking discoveries of modern scholarship on medieval European documentary traditions has been just how widespread forgery was. Almost every major religious house was involved in falsifying...

Continue reading...Vestez vos dras, biau douz enfaunz, Chaucez vos brais, soulers, et gaunz. […] De une corroie vous ceintez — Ne di pas ‘vous enceintez‘, Car femme est par home enceinte Et de une ceinture est ele ceinte. Put on your clothes, my sweet child: don your breeches, shoes, and gloves. Lock up...

Continue reading...One of the pillars of the Medieval Studies community at Exeter, Emma Cayley, left the university over the summer to take up a post as Head of School of Languages,...

Continue reading...

As my colleagues at Exeter know, I have spent the past few years looking at the concept of news in the Middle Ages. I’ve been considering what the idea of...

Continue reading...Five hundred years ago, Henry Courtenay, earl of Devon (d. 1539), marked the coming of the New Year with a rare and costly gift for his king, Henry VIII: oranges...

Continue reading...I’m at the beginning of a new project on ‘Popular Healing: Christian and Islamic Practices and the Roman Inquisition in Early Modern Malta’ (not medieval, but you can’t have everything),...

Continue reading...This week marks the 750th anniversary of the last translation of the relics of Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey, in 1269, to the new shrine created at the direction...

Continue reading...This year’s annual student colloquium for the Society for Medieval Archaeology is being organised by a group of our CMS PGRs and will be held here at the University of...

Continue reading...Jack Pettitt, an Exeter graduate and secondary school history teacher, has spent his summer filming a series of online videos to help his students learn about the Normans. To make...

Continue reading...This week we have a guest post from Sheila Sweetinburgh at Canterbury Christ Church University, who is reporting on the Fifteenth Century conference, held in Exeter last week, with a...

Continue reading...Tuesday 16 July 2019 marks the 650th anniversary of the death of John Grandisson (1292-1369), Exeter’s longest-serving bishop. The cathedral and the diocese have been shaped by many hands over...

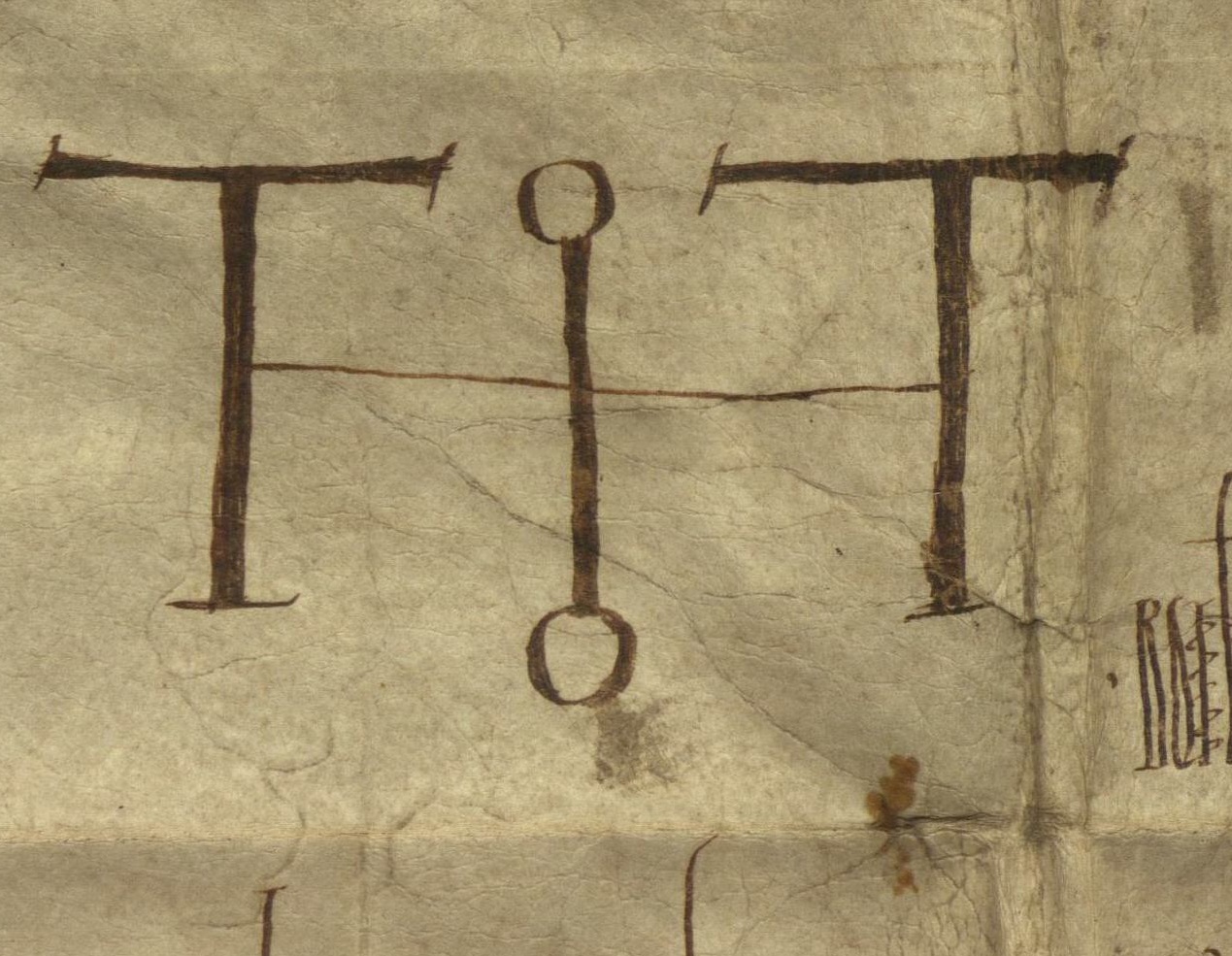

Continue reading...May is an exciting month for Exeter’s Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. As a part of Dr Levi Roach’s AHRC funded grant ‘Forging Memory: Falsified Documents and Institutional History in Europe, c.970-1020’, a...

Continue reading...The scorching summer of 2018 was a great gift for archaeologists. For the first time in almost two decades an unbroken dry spell brought features below the surface of the...

Continue reading...The scorching summer of 2018 was a great gift for archaeologists. For the first time in almost two decades an unbroken dry spell brought features below the surface of the...

Continue reading...The Centre for Medieval Studies at Exeter hosts a lively programme of activities throughout the year, a number of which are only possible through the generous support of Emeritus Professor...

Continue reading...The Centre for Medieval Studies here at Exeter is well-known for its sense of community, and for the value it places on the exchange of ideas in an informal and...

Continue reading...I’m very pleased to announce that the Routledge History of Medieval Magic, edited by Sophie Page (UCL) and me, has been published. As editors we’re very happy with it and...

Continue reading...We’re happy to announce that the new Warhorse project in Archaeology, led by Prof. Oliver Creighton, now has a website and blog up and running. ‘Warhorse: the Archaeology of a...

Continue reading...We’re pleased to announce that two books with medieval themes written by Exeter academics have been shortlisted for the 2019 Current Archaeology Awards, in the ‘Book of the Year’ category...

Continue reading...Exeter will be hosting the Fifteenth Century Conference this September, an annual conference for anyone with interests in the Fifteenth Century. This has come about mainly because of the hard work of...

Continue reading...John Grandisson, the bishop who presided at Exeter in the turbulent middle years of the fourteenth century – the age of the papacy’s Avignon exile, the Black Death and the...

Continue reading...It’s that time of year again – funding deadlines for students applying for PhD study are coming up. Staff at the Centre for Medieval Studies are always keen to hear...

Continue reading...In my previous post for the Centre for Medieval Studies blog, I promised a much-needed follow-up to my interview with the storyteller Rachel Rose Reid, whose retelling of the medieval...

Continue reading...This week, we’re advertising a call for papers for Exeter’s postgraduate history journal, Ex Historia. Over the years quite a few of our medieval PhD students have been involved with Ex...

Continue reading...This week, we’re advertising a call for papers for Exeter’s postgraduate history journal, Ex Historia. Over the years quite a few of our medieval PhD students have been involved with Ex...

Continue reading...It’s not all that often that some news genuinely makes you jump out of your seat in excitement. One such occasion came for me a couple of months ago, when...

Continue reading...Well, term has started and campus is suddenly full of students again. Here in the Centre for Medieval Studies we’re catching up with existing colleagues and students, as well as...

Continue reading...Inspired by Levi’s call for Leeds and Kalamazoo papers on the blog a few weeks ago I thought I’d post one of my own for Leeds 2019… I’m currently in...

Continue reading...In June and July 2018, Julia Hopkin, an MA student in experimental archaeology at Exeter, spent some time in Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives, funded by the university as part of the...

Continue reading...

As part of my ongoing project on medieval forgery, I am pleased to anounce the following Call for Papers on ‘Forging Memory: False Documents and Historical Consciousness in the Middle...

Continue reading...A couple of weeks ago, on Saturday 17th March, a few staff in the Centre had a stall at the University’s Community Day to showcase some of the research we...

Continue reading...

As a part of my AHRC-funded project on forgery, I had the singular pleasure of visiting the Hessisches Staatsarchiv in leafy Darmstadt last term. There are many reasons why archival...

Continue reading...

As a part of my AHRC-funded project on forgery, I had the singular pleasure of visiting the Hessisches Staatsarchiv in leafy Darmstadt last term. There are many reasons why archival...

Continue reading...As an undergraduate, I spent quite a lot of time in and around Emmanuel College, Cambridge. One of my best friends was a student there, and in the spirit of...

Continue reading...At the end of January I went to a workshop at the University of Cologne, run by a.r.t.e.s. Graduate School for the Humanities and expertly organized by Eva-Maria Cersovsky and...

Continue reading...Eminent Churchillians have been all a-quiver. Darkest Hour has carried their subject far beyond his familiar home in the Culture pages of the serious newspapers to set him trending, everywhere....

Continue reading...Interviewers: Tom Douglas and Max Blore (3rd year undergraduates) On Wednesday 22 November 2017, Professor Conrad Leyser (University of Oxford) visited the Centre of Medieval Studies here at the...

Continue reading...‘We’ve found a body. We’d like you to help us with our enquiries’. An unnerving telephone message to pick up amid the usual end-of-term pressures, but as it turned out...

Continue reading...‘We’ve found a body. We’d like you to help us with our enquiries’. An unnerving telephone message to pick up amid the usual end-of-term pressures, but as it turned out...

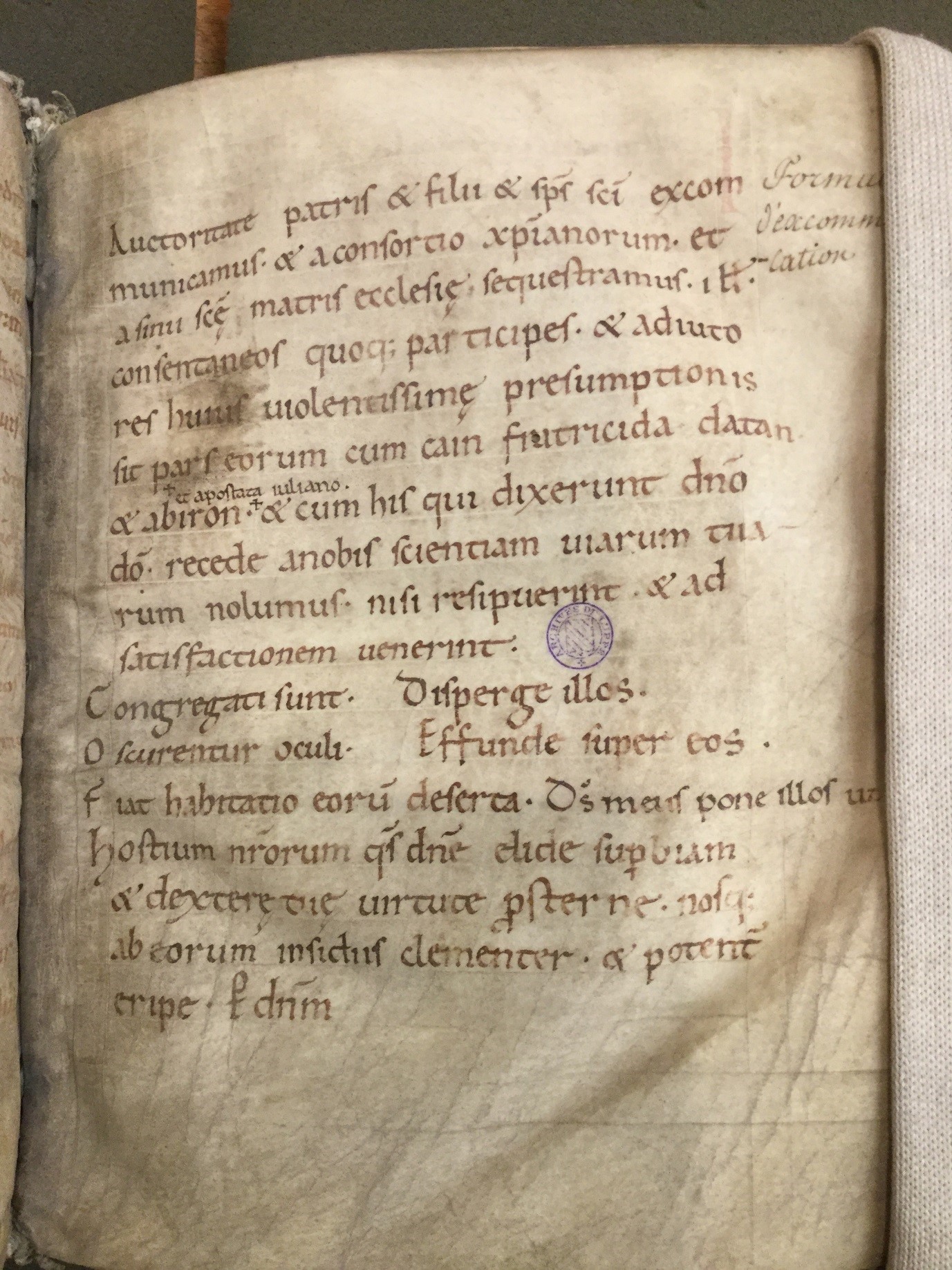

Continue reading...In my PhD research, I am looking at the local pasts that were communicated through liturgy in the tenth century in a metropolitan city on the Moselle river: Trier. My...

Continue reading...Appropriately – given that it was Halloween – I spent part of reading week in the archives researching the history of magic. Dr Alex Mallett (formerly of Exeter, now based...

Continue reading...Appropriately – given that it was Halloween – I spent part of reading week in the archives researching the history of magic. Dr Alex Mallett (formerly of Exeter, now based...

Continue reading...This term I am based at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT, working with the Traveler’s Lab research group. The Traveler’s Lab is a small network of scholars interested in medieval...

Continue reading...This term I am based at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT, working with the Traveler’s Lab research group. The Traveler’s Lab is a small network of scholars interested in medieval...

Continue reading...Thinking about doing a doctorate in Medieval Studies, but unsure how to turn that initial idea into a formal funding proposal? This post offers some guidance on the process –...

Continue reading...Having finally submitted my thesis on Norman ethnic identity, I decided to celebrate by taking a holiday. And what better place for a young Norman historian to visit than Sicily?!...

Continue reading...Last July Cheryl Cooper, who had just completed a History degree at Exeter, did a student internship (funded by the College of Humanities and the Widening Participation scheme) looking at resources for...

Continue reading...Last July Cheryl Cooper, who had just completed a History degree at Exeter, did a student internship (funded by the College of Humanities and the Widening Participation scheme) looking at resources for...

Continue reading...When I started my PhD in medieval archaeology the reason was simple. There was a very clear gap in the understanding of medieval castles I wanted to address and formalising...

Continue reading...Medievalists love their subject. As a medievalist, you not only spend most of your working week researching the medieval past, but you probably visit medieval sites in your spare time...

Continue reading...

It brings me great pleasure to announce that the Arts and Humanities Research Council has seen fit to fund my new project, ‘Forging Memory: Falsified Documents and Institutional History in...

Continue reading...

Last week I went to the annual summer conference of the Ecclesiastical History Society, which was held here in Exeter. This year’s theme was Churches and Education, and it attracted...

Continue reading...

The annual International Medieval Congress hosted by the University of Leeds in July (and known affectionately as the ‘IMC’ or ‘Leeds’) is the highlight of the European medieval calendar –...

Continue reading...Recently, on 24 June, I went to the annual mini-conference of the Devon and Cornwall Record Society, held at the Guildhall in Exeter. This year’s theme was Late Medieval and Reformation...

Continue reading...

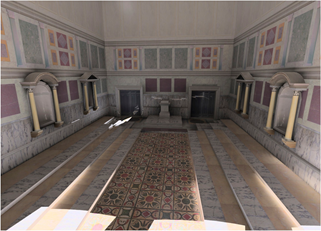

What happens after empire? In an age in which Europe continues to grapple with its colonial past, there could scarcely be a more timely question. Yet while the Fall of...

Continue reading...For some years now St Nicholas’ Priory, in the area of Exeter off Fore Street known as ‘the Mint’, has been closed to the public. However, conservation work continues and...

Continue reading...What better way to celebrate the end of exam marking at Exeter than to spend a summer’s day wandering around medieval sites in the Southwest? On 1 June, two PhD...

Continue reading...

It’s unusual for British universities to be in a position to buy medieval manuscripts. Yet the recent publicity given to the discovery of a unique leaf from the Sarum Ordinal...

Continue reading...There has been a huge proliferation of online resources for research and teaching in Medieval Studies in recent years, so much so that it’s hard to keep track of them...

Continue reading...There has been a huge proliferation of online resources for research and teaching in Medieval Studies in recent years, so much so that it’s hard to keep track of them...

Continue reading...I recently participated in a campus visit for Year 9 and 10 school pupils as part of Exeter’s Widening Participation scheme to encourage a larger pool of students to consider...

Continue reading...In the heart of the American Mid-West, two and a half hours from Chicago, in the University twin town of Urbana-Champaign is a rare gem of a collection of medieval...

Continue reading...In the heart of the American Mid-West, two and a half hours from Chicago, in the University twin town of Urbana-Champaign is a rare gem of a collection of medieval...

Continue reading...In just a few years, family history research has become something of a cultural phenomenon. Proof of this will be apparent to any professional researcher arriving at the National Archives...

Continue reading...Wednesday 29th March saw medievalists from across the University and the city gather for the climax of the Medieval Studies calendar in Exeter. This annual day of events, generously sponsored...

Continue reading...The Medieval Research Seminar has been particularly active of late. Hot on the heels of Anne Lawrence-Mathers’ fascinating discussion of medieval magic and Sarah Hamilton’s insight into reading and understanding rites, we...

Continue reading...

Interviewers: Éléonore Raymakers, Emma Prevignano and Lauren Lloyd The second part of the interview conducted by our undergraduate magic specialists with Prof. Anne Lawrence-Mathers, when she presented a paper at...

Continue reading...

Interviewers: Éléonore Raymakers, Emma Prevignano and Lauren Lloyd On Wednesday 15 February, Professor Anne Lawrence-Mathers (University of Reading) visited the Centre for Medieval Studies here at the University of Exeter....

Continue reading...

Demons appear in all kinds of medieval sources, but often feature particularly in the records kept by saints’ shrines of miracles performed by the saint. Among many other illnesses and...

Continue reading...

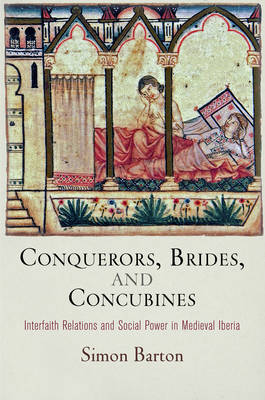

Arabic has not tended to be regarded as a language of medieval Europe, despite being spoken across parts of the Iberian Peninsula for nearly 800 years and indeed elsewhere too...

Continue reading...

I’m very much looking forward to joining the community at Exeter this coming autumn, and I would like to take the opportunity to introduce myself and my work. Currently I’m...

Continue reading...

The following is a review of John Eldevik’s Episcopal Power and Ecclesiastical Reform in the German Empire (CUP, 2012). It was originally produced for an online review platform; but, since...

Continue reading...I’m delighted to see the fruits of a recent Exeter-based archaeological research project on the conflict landscapes of the 12th century published in book form. The co-written title Anarchy: War...

Continue reading...I’m on research leave this term and working on an ongoing project which looks at attitudes to infertility and childlessness in medieval England. Although there has been a great deal...

Continue reading...Not all manuscripts are pretty. Many, of course, are absolutely gorgeous: one need only look at the British Library exhibition on the Royal Manuscripts collection from 2011, or the accompanying...

Continue reading...As any veteran of the funding process knows, the next best thing to the elusive gold dust of ‘reveIance’ is the calendar-bound quality of ‘timeliness’. And nothing demonstrates timeliness or...

Continue reading...Commenting on the inability of human societies to predict forthcoming calamities, the Los Angeles Times recently ran a comment piece headed ‘No-one expects the Spanish Inquisition – or Donald Trump’....

Continue reading...

The late medieval English cleric gets a pretty raw deal in film, TV and in popular histories. Where they appear at all, they are often ciphers, materialising merely to fulfil...

Continue reading...Mid-morning on 28 October I received an urgent request from BBC Spotlight to provide historical background on an emerging news story in Exeter: the Royal Clarence Hotel had just caught...

Continue reading...I finished my last post with the claim that, for video game medievalism, 2016 has really been building up to something greater than itself in 2017. Indeed, there is plenty...

Continue reading...

2016 has had its fair share of popular medievalism in the media. However, for video game medievalism in particular, this year has been one of record-smashing and new frontiers. From...

Continue reading...

Last month in the baroque splendours of the Brevnov monastery in Prague, HERA launched its third joint programme of European research on ‘Uses of the Past’. Amongst the 18 projects being...

Continue reading...

I am pleased to be able to say that Orderic Vitalis: Life, Works and Interpretations, the first volume of essays on one of the most significant and influential historians of...

Continue reading...On 14 October 1066 one of the most renowned battles in Britain was fought between William, Duke of Normandy, and Harold, King of England, near the town of Hastings. This...

Continue reading...On Friday night I attended a screening of the 1922 film Robin Hood at the Barbican Centre in London. In addition to bringing a silent cinema classic back to the...

Continue reading...Having recently passed the viva for my thesis ‘Painful Transformations: A Medical Approach to Experience, Life Cycle and Text in British Library, Additional MS 61823, The Book of Margery Kempe’,...

Continue reading...At the opening and closing the BBC’s adaptation of Wolf Hall I was asked to share my thoughts on Thomas Cromwell with presenter Simon Bates on BBC Radio Devon’s ‘Good Morning...

Continue reading...

This past month the Museum of Somerset in Taunton has enjoyed a particular honour: it has been host to the Alfred Jewel. Found in North Petherton (Somerset) by Sir Thomas...

Continue reading...Barely a century after the Muslim invasion of Spain in 711, a tomb was found in Galicia and declared to be that of the apostle St. James. The conquest had...

Continue reading...When Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragon took Granada from the Moors in 1492, their propaganda claimed it as a heroic victory marking the culmination of an 800 year...

Continue reading...Recently three academics associated with the Centre for Medieval Studies visited the Cathedral Archives in Mdina, Malta, as part of a research project on ‘Magic in Malta, 1605: the Moorish...

Continue reading...A couple of weeks ago I received an email from the BBC History Magazine website asking me if I’d be willing to draw up a quiz for their Medieval Week....

Continue reading...

Every year, on the Sunday before 5 October, the feast day of St Froilán, the inhabitants of the Spanish city of León celebrate a popular festival known as Las...

Continue reading...Of the many celebrated names connected with medieval Exeter, Bracton is one of only a handful to claim global recognition. Bracton is known to students and practitioners of law throughout the Anglophone...

Continue reading...Books of Hours are perhaps the most familiar of all medieval manuscripts. Their intricate miniatures have become a universal symbol of European art and culture before the advent of the...

Continue reading...Exeter medievalist Eddie Jones has been awarded AHRC funding for an international research network to explore the remarkable intellectual and spiritual legacy of Syon Abbey. Syon, the Birgittine monastery of...

Continue reading...Exeter’s Centre for Medieval Studies working in collaboration with medievalists at Bristol and Cardiff have secured £45K to establish a regional research cluster to work within the new Great...

Continue reading...