In our very first seminar, a question was raised which struck me as something that I had never fully considered before: when was the last time you picked up a book and read it without knowing anything at all about it? Well, of course I’ve read many books, the plots of which I’ve not known about beforehand, despite today’s TV culture which has serialized nearly every book that has a penguin stamp on it. However, the question got me thinking about how exactly I decide on which books to read and devote my time to.

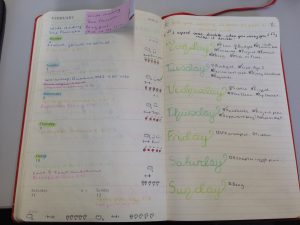

Imagine I’m perusing a library, or a bookshop. I’d like to picture myself in a quirky secondhand shop where the books smell of moths and chewing tobacco, rather than suffering under the fluorescent glare of a WHSmith. Of course, first and foremost, I read the title. I need it to grab my attention and, I will admit, I am notorious for judging the book by its cover (I clearly learnt nothing from my primary school PSHCE lessons – Sorry Miss Salisbury!). I’m a tactile person so a book with embossed lettering or a crisp, matt sleeve is probably what my fingers will settle on first as I run my hands along the row of spines sitting upon the shelf. Secondly, I’ll flip the book over. Read the blurb. I like to have a clear idea of genre, plot and target audience, just to see if the book fits. For me, reading the blurb is like trying on a pair of jeans in a shop changing room. If it looks good, and suits my style, I’ll buy. Now who has made the commendations? If anyone from the Guardian has given it a thumbs up then I’m sure to keep hold of it. If I see the words “Daily Mail”, that book is going right back on the shelf without a second glance. Usually I will stick to the authors which I’ve heard of before and perhaps I’ve read some of their other work. Or I will select the authors which other people, whom I admire (or whom I loathe and have a secret wish to trump intellectually) have recommended to me. Book chosen, tea made, and scented candle lit, I’ll begin as most of us do, unless you possess the virtuous patience and discipline it takes to read the preface, with Chapter One. But if after twenty or so pages the book is not kindling that flutter of intrigue which occurs when I get hooked on a good story, and I find myself checking my Facebook notifications every other paragraph, then I’m afraid I will never meet Chapter Two.

So I came up with an idea. What if I actually tried reading a book that I had never encountered? Never seen the book on a best-seller’s list, never heard of anyone else reading it, never come across the writer, wasn’t even familiar with the title, let alone knew anything about its content. I thought it would make a good experiment to further consider exactly how we read and how our preconceptions of a book inform our overall understanding of it and affect our reading experience.

Even picking up a book ‘randomly’ myself would be in some small way informed by all my prejudices. So I recruited a friend (who studies Natural Sciences and stays away from the library like a vampire does the sun) to go into the forum on our Streatham campus and choose for me a book to read. She reported back five minutes later with Not Not While The Giro by James Kelman. Never heard of it. It took all my willpower not to turn the book over and start scanning the back for information, but I simply opened the front cover and started to read.

I read for about an hour and I thoroughly enjoyed the session. Not having any prior expectations made the reading experience a relaxing one, and instead of taking in the words while simultaneously evaluating whether the book was living up to reviews, or anticipating the plot that was promised in the blurb, I just read. Each chapter introduced me to new characters and presented me with a short moment of interaction; a conversation with an old man in a pub, whose drinking partner was found dead in his apartment, a brusque Irish man collecting money from a Labour exchange, an awkward date in a bachelor house which resulted in a merciless eviction. I was not entirely clear when it was set or who these people were and what their connection to each other was, which often made me feel disorientated, yet this encouraged my imagination to run on and construct a story in my head. The more I read, the more I began to piece things together and locate myself, but I found overall that my interpretation of the book was freed up noticeably more than in regular reading experiences.

What I found surprisingly exciting about this mode of ‘innocent’ reading was that the book in question was not something that I would have actively chosen to read myself. I was taken out of my comfort zone and forced to read a work that was heavy with dialogue and lacked long descriptive paragraphs that establish character and backstory. It felt more like reading scenes in a play than chapters in a novel, and I found the overall tone of the book rather terse. The book was clearly not aimed at my demographic (the young female reader) as many of the references to football teams, watery ales and war veterans went over my head. But I have to say I was pleased that I gave it a chance and will probably keep reading to the end.

So I would recommend having a go at this exercise. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with some context, but I believe that we as readers should aim to be a bit more conscious of what is preventing us from trying new things!