Ahh happiness. It sounds so simple doesn’t it?

I don’t think I ever thought I would be writing something public about what I think happiness means to me. Because that’s the thing about being happy, it is really personal. What makes one person happy won’t make another person feel quite the same, and as a result I don’t want this post to become a guide, or even some sort of ‘Agony Aunt’ advice clinic. Rather, this is just me, having been inspired by a wonderful lecture on literature and happiness, trying to work out what I think being happy means to me.

So here goes…

Why do we want to be happy?

It seems like being happy is the new craze. From feel good playlists on Spotify, to bullet journaling accounts on Tumblr, to Humans of New York’s inspirational photo stories on Instagram, to videos of real-life heroes on Facebook, to my new Positively Pooh book I got for my birthday, it seems like society is saturated with ideas on how to be happy, the importance of being happy, and of other people’s happiness.

Yet, on the flip side, within this bombardment of happiness is the potential of putting pressure on people to be happy, even when they’re not. Sometimes, pretending that we are happy could result in things getting worse.

Late last year, I went to watch a musical called A Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer.

Yup, it was a musical about cancer.

I was intrigued to say the least. However, confident in the abilities of The National Theatre, Complicité, and director Bryony Kimmings, I went with two friends to go and see it.

There are enough reviews online that will tell you how inspiring, sensitive, heart breaking, self-aware and honest this production was. Never in my life have I been moved by a piece of theatre. There was not one member of the audience who was not crying, and not just crying, I mean crying.

However, I would like to draw attention to one moment in the performance that responds to this idea of what it means to be happy. In one song, the cast (whose characters were in fact entirely representative of real people), sang about social media’s influence on how cancer patients think about cancer. The song made a poignant criticism of the many videos online that show cancer patients being brave, strong, resilient, and happy. The song acknowledged that cancer is not like this all the time, and sometimes you don’t want to be brave, you need to let yourself feel like shit.

And this applies not just to the issues being debated within the musical, but to everything.

The importance of being happy is being delivered to us in bucket load. Even the government have invested in the understanding of the impact of happiness through their Public Happiness and Wellbeing Agenda.

And I don’t want to criticise this. I think it is brilliant that we are becoming so much more aware of the importance of being happy, and finding your own happiness. It just makes me wonder to what extent does the world around me shape my desire to be happy, and whether, by extension, the desire to be happy has shaped who I am.

What does happiness mean to me?

I think I first started becoming hyper aware of my desire for happiness when I was doing my A Levels, I presume in response to my record levels of stress! Having gone through a stressful time in my life, I came out the other side with a desire, not necessarily to be happy, but to be the best and happiest version of me. And this is a thought process that has persisted ever since.

I recognised that ‘stressed Emma’ was not who I wanted to be. I would push away those closest to me and shut myself off from everything. And I’m not like that. And more importantly I don’t like being like that.

Over the years (that sounds like I am old and wise, I am neither old nor wise), I have worked out that I absolutely love making other people smile, and I think this has significantly shaped how I have grown up (though I like to think I am not yet fully grown). Anything that I can do to make others feel happy, results in me feeling happy too.

And this isn’t anything profound. It’s just little things like being bubbly and energetic when you can see that those around you are super tired, just to try and perk them up. Or it’s smiling at someone when you’re all in a really nervy situation, waiting outside an audition room for example, just to show them that you’re nervous too, but it’s going to be okay. None of the things I do on a daily basis are big gestures, but I think I get so much happiness out of trying to make others feel happy and at ease.

I’m not sure that makes any sense. I suppose a lot of my ‘positive thinking’ links to the people I am around, truly valuing those people, and wanting to make them happy.

I know someone who can explain this far better.

The problems of my version of happiness

I would argue that I am a happy person. And when it comes to other people, I am super duper positive. In fact, I believe in my closest friends and family more than I believe in myself.

And there’s the paradox.

Yes I would say that I am happy, but at the same time I am acutely aware that I have low self-esteem, and I often am rather pessimistic when it comes to my own endeavours.

So I suppose sometimes my positivity towards others can be mistaken for me having a positive and optimistic outlook on my own life.

Now I don’t want to dwell here. But this begs the question of how I can feel happy, but still struggle to feel proud of myself, or confident, or calm in stressful situations.

And I suppose, now I think about it, that’s because happiness and positivity are different. If happiness for me is mostly an external process, defined more so by the happiness of others, then positivity is a much more internal thing for me.

So when something gets me down, I don’t think that means I am unhappy necessarily. Instead, the feeling I have is more closely linked to self-esteem and positivity.

HOWEVER

(Let’s move on before this gets depressing)

I am totally aware of this aspect of my personality. As a result I consciously work towards trying to raise my self-esteem and feel more positive about myself. In fact, being happy in general really helps me with this, because happiness gives me the energy, determination, enthusiasm, and support to do so.

The Little Things

There are lots of little things that I do purposely, though now they feel more like habit, to make me feel more happy, and in turn more positive and confident. I have compiled them into a list, perfectly illustrating one of the things I do to make myself feel more self-confident: I write lists.

- Having close relationships and cherishing my nearest and dearest. I am a super lucky human being because I am surrounded by the most wonderful, lovely, kind, generous, fun, determined and ambitious group of people in the whole entire world.

- Gratitude diary Everyday, I write one thing in my gratitude diary that has gone well. That means that even if I think my day has been horrible, I have to find something good in it. And do you know what? I always do! The things in my diary range from ‘The man who was singing out loud while walking down the high street listening to music through headphones’ to ‘IT’S CHRIIIIIIIIIISTMAAAAAAAS!!!!’ to ‘I had the perfect day at the Donkey Sanctuary with the housemates’. Again, nothing profound, just the little things.

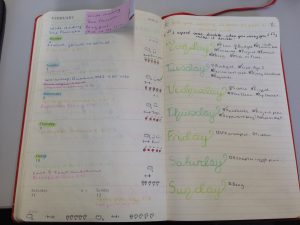

- Planning and organising I LOVE ORGANISING! It is my favourite thing. Everything is colour-coded. I have lots of stationary. At the top of my weekly plan, I always write a positive thought and a song lyric. It’s just a little something I have added to increase the positivity out of something that already fills me with joy.

- Photographs, memories and trinkets I have photos all over my room. It means that the first thing I see when I wake up are the people who I love the most in the world. I am someone who does place importance on anything with a memory attached to it. Which explain the slightly terrifying mini-figure of the Loch Ness Monster on my shelf…

- Doing the things that I love I sing in a choir, I sing in the shower (sorry housemates), I go to the theatre, I do yoga in the morning and fall over a lot, I eat a lot of chocolate, I watch ‘Naked Attraction’ with my housemates, I like to sit with my legs crossed by my head like a pretzel, I will always opt for the cosy night in over the crazy night out, I do pole fitness (no Nanny, it is not my ‘back-up plan’ for if everything goes wrong post-graduation)… And I do a degree that I love.

- Take some risks and always try your best Sometimes you have to push yourself out of your comfort zone.

- Not all days will be good days Off days are normal and they happen all the time. I am gradually learning to accept that some days won’t be as productive, or full of joy, or energetic as others, and that’s allowed.

- I smile… a lot

Tah-dah!

So that’s my big splurge about my own view of happiness. And do you know what?

I am feeling pretty happy now I have written it 🙂