This post is written by Katie Harling-Lee.

There is a recent trend for contemporary novels which feature classical music, set during political or armed conflict. This trend can be found beyond the novel and in wider popular culture, and whilst my research focuses on representations of classical music in the contemporary novel, these novels inform and are part of the wider popular imagination, as they can be described as ‘popular high culture’: ‘literary novels that appeal to scholars whilst also functioning as entertainment on the contemporary literary marketplace’.

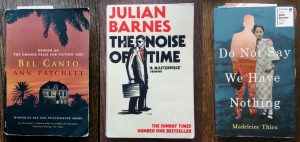

In my research I use the term ‘musico-literary novel’: ‘a novel which thematically engages with musicological and music philosophy concerns throughout its narrative’.[1] Examples include Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien (2016), The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes (2016), The Cellist of Sarajevo by Steven Galloway (2008), and Bel Canto by Ann Patchett (2001).

The novels represent classical music in an in-depth, extensive way, depicting imagined experiences of music listening, music practise and performance, and musical composition. Some of these novels only feature classical music, whilst others include various styles or types of music, yet these particular novels maintain a primary focus on classical music within their conflict context.

In analysis of the novels’ representations of classical music, a common thread occurs. An element of classical music that is repeatedly valued is its established tradition, e.g., formal structures and etiquette, global reach, and its centuries-long tradition. Anna Bull has importantly highlighted the structures of control which are present in the classical music tradition, and the issues this raises,[2] yet these novels complicate such criticisms through their use of the armed/political conflict context. Depicting the human desire for some semblance of control in a chaotic, conflict zone, these novels present a different perspective on classical music’s controlling elements: when a character’s country appears to be falling apart, the character turns to classical music as a source of survival.[3]

Notes

[1] Katie Harling-Lee, ‘Listening to Survive: Classical Music and Conflict in the Musico-Literary Novel’, Violence: An International Journal, 1.2 (2020), 371–388 (p. 373).

[2] Anna Bull, Class, Control, and Classical Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[3] What makes this valuation of music in a conflict setting even more thought-provoking is the real-life parallels that can be found in musicians’ memoirs (e.g., The Secret Piano: From Mao’s Labour Camps to Bach’s Goldberg Variations by Zhu Xiao-Mei (2012))

Katie Harling-Lee is a Wolfson Foundation Doctoral Scholar at Durham University.