Our next Screen Talks will be on Monday 18th November, 6.30pm at Exeter Picturehouse. Hannah Lewis-Bill a Phd researcher in the Dept of English at the University of Exeter) will introduce Oliver Twist, the 1948 adaptation by David Lean. Hannah researches Dickens and the representation of China in his novels through commodities such as tea and silk

Join the event on Facebook and find out more here.

Booking Information: Book online, call the Box Office 0871 902 5730 or buy tickets on the door (half price for students on Mondays).

Hannah has written a guest-blog post for us on the film:

The opening of David Lean’s 1948 black and white version of Oliver Twist is bleak, powerful and dramatic: the ragged branches, the fractured shots of the pregnant woman’s face as she struggles to her final destination and the lashing rain are certainly atmospheric and yet are so very different from Dickens’s own opening. Dickens’s novel opens with the workhouse with a soon-to-be expiring mother and Oliver’s entry into the world and workhouse.

Oliver Twist tie-in novelisation, 1948, from the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum Collection

The story of Oliver Twist is a familiar one and Lean’s interpretation is for the most part faithful. Oliver is born in the workhouse and sent to be looked after by the parish authorities from where he is then sent on to various apprenticeships. He then runs, quite literally, into the Artful Dodger who introduces him to Fagin (Alec Guinness) who, spotting Oliver’s potential, sets about trying to turn him into a successful pickpocket. The plan to enact Oliver’s premature expiration from this world is then also gradually undertaken. I could say more but for risk of spoiling the parts for those less familiar and to maintain the suspense for our viewing at the Exeter Picture House on Monday 18th November I will stop there! It is, though, worth considering what has been left out and why and that is one of the points I will reflect on during my talk on Monday; is there something to be said for cinematic exclusions and do these exclusions add another dimension?

It is sometimes difficult I think to separate the parts of the novel familiar to us because we know them from Dickens from those scenes that are so familiar because we know them from the screen. Indeed does it matter? In my opinion it does. In order for a novelist to continue to resonate culturally and socially it is often helpful for their work to be adapted in new ways to reach new audiences be this through the screen, stage or reimagined through adapted versions of the story. In many ways this version of Dickens’s novel, reconceptualised in this way, heightens an awareness of the cultural concerns in Dickens’s time and also at the time of Lean’s production. Anti-Semitism cannot in this adaptation be ignored. Fagin is arguably the best known character from Oliver Twist and Dickens’s representation of this character is undoubtedly anti-Semitic and so too I would argue is Lean’s. Whilst Dickens never directly states that Fagin is Jewish, his stereotypic depiction leaves us in little doubt of his cultural heritage. Indeed later in Dickens’s literary career upon conversing with some Jewish friends they explained the damage his representation of Jews had done and he was horrified. It was this which led him to create a sympathetic and thoughtfully composed Jewish character in Our Mutual Friend in an attempt to undo some of the damage. The fact that Lean, seemingly determinedly, negatively and stereotypically depicts Fagin is therefore even more problematic. Taking influence from the images created by Cruikshank’s (the man who illustrated Oliver Twist for Dickens) Lean purposefully heightened certain features such as his nose to create a stereotyped Jewish aesthetic. Produced, as this film was, during the Second World War, and the atrocities enacted on the Jewish population in particular, seems a very questionable decision. It did cost Lean as it meant that the film was not released in the US until 1951 and, when it was released, 7 minutes of the film including the questionable representation of Fagin were omitted. The moment we first see Fagin played by Alec Guinness is an uncomfortable moment and an important one for that very reason.

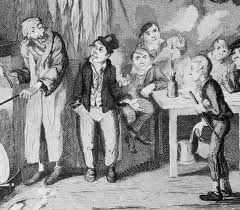

George Cruikshanks, ‘Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman’, (1838)

Speaking personally for a moment, my own research considers Dickens, China and tea and the way in which commodities function in shaping a cultural consciousness of the world beyond Britain. Whilst a reading of the novel would certainly produce readings of China what is interesting about a reading of the film is the significant role objects play. From the necklace that features so prominently at the start of the film on Oliver’s mother’s neck, the coffins, the signage, the handkerchiefs, wallets, and the jewellery that Fagin collects there is always a cornucopia of objects that support the hidden or more subtle contexts of the cinematic plot. To an extent the money that is hoarded and exchanged is another object that is significant to the running of the den and London more broadly and, it can be suggested, Oliver becomes the ultimate object of everyone’s desires. This is something that might again be discussed in greater detail when we come together to talk after the film on Monday: what is the effect of these hidden layers to the plot and what can they add to our viewing of the film? For now though I hope to have presented a new twist on both Dickens’s and Lean’s Oliver Twist and left you feeling as though, like Oliver you would like more!

Hannah has written about Dickens and commodities. She has an essay entitled “From ‘The Great Exhibition to the Little One’ to ‘China with a Flaw in It’: China, Commodities and Conflict in Household Words“ in Mackenzie, H. & B. Winyard (eds), Charles Dickens and the Mid-Victorian Press, 1850-1870 (Buckingham: University of Buckingham Press, 2013).

Read more about Hannah’s research here, and follow her on Twitter: @hlewisbill